Å kombinere tid og rom. Tidsrom som et organiserende tankebegrep for narrativ historieundervisning

Med den hensikt å konstruere historiske narrativ i et undervisningsinnhold, trenger lærere tilgang til tankebegreper. Denne artikkelen undersøker, i historieundervisning i svensk videregående skole, hvordan ulike kombinasjoner av tid og rom kan utgjøre slike tankebegreper.

Med den hensikt å konstruere historiske narrativ i et undervisningsinnhold trenger lærere tilgang til tankebegreper. Denne artikkelen undersøker, i historieundervisning i svensk videregående skole, hvordan ulike kombinasjoner av tid og rom kan utgjøre slike tankebegreper. Artikkelen bygger på semistrukturerte intervjuer med lærere som beskriver innholdet i undervisningen de har gjennomført skoleåret da intervjuene fant sted. I lærernes uttalelser i intervjuene, sammen med lærernes undervisningsmateriell, har seks forskjellige måter å kombinere tid og rom i historieundervisningen blitt identifisert. De tidsrommene som ble identifisert kunne siden deles inn i tre ulike kategorier. En første kategori der tiden beveger seg fra fortid til nåtid med en tydelig inndeling i tidsperioder og geografisk tilhørighet. En kategori nummer to med betoning på historiske lange linjer der ulike spørsmål blir fulgt. Her blir det lagt mindre vekt på inndeling i perioder og på geografi. Avslutningsvis et tidsrom med tidsperspektiv som vekslende beveger seg mellom nåtid og fortid med fokus på ulike historiske spørsmål. Hovedkonklusjonen er at de tidsrommene som blir identifisert på en gjennomgripende måte, bidrar til å forme de historiske narrativene som blir valgt i undervisningen. Utvalget av tidsrom i undervisningsinnholdet har derfor potensiale til å forme både historieemnets innhold som hensikt. På den måten bidrar denne artikkelen til en diskusjon om hvilke tankebegreper som finnes tilgjengelig for lærere når de uttrykker innholdet i skolens historieundervisning.

Combining time and space: An organizing concept for narratives in history teaching

To construct a historical narrative in teaching content, teachers need subject-specific tools. This article explores how, in a history course taught in Sweden, different combinations of time and what can be called ‘space’ can operate as one such subject-specific tool.

To construct a historical narrative in teaching content, teachers need subject-specific tools. This article explores how, in a history course taught in Sweden, different combinations of time and what can be called ‘space’ can operate as one such subject-specific tool. To collect data on how this might be done, semi-structured interviews were conducted with teachers who described the content of a history course they taught. Their statements in interviews, alongside examples of their teaching materials, were used to identify six different ways of combining time and space in history teaching. These combinations were then grouped into three categories: one, when time runs from the past to the present and where there is a strong emphasis on periodization and geographical location; two, when time runs from the past to the present but there is less emphasis on periodization and geographical location and a greater emphasis on issues or themes across long periods of time; and three, when the time perspective is directed either forward or back in time and focuses on different aspects of the notion of ‘space’. The overall conclusion is that time and space categories can help to structure teaching content, mainly because they organize in specific ways the historical narrative on which that teaching content is based. The choice of time and space in teaching content can, therefore, shape the way history is taught as a subject. The results of this study contribute to a discussion of the subject-specific tools that are available for teachers when they construct narratives in their teaching of history.

Introduction: the research problem

One thing we did, involved the labor market in the Middle Ages. We used material from a museum. Then we looked at the rule of law in the Middle Ages, and for that we used historical material as well. When we looked at the labor market in the Middle Ages, it was all about types of occupations. And about living conditions. What life was like.

(Interview Linnea)

And then the next step is to look at the general characteristics of the late Middle Ages and how the transition to the early modern period begins, when nation states begin to form. We also look a little bit at the causes of rise and fall. What led to the rise of the Middle Ages? Political stability, climate change and other things increased economic production.

(Interview Lennart)

It can be said that the work of teachers, for at least a century, has been to take a subject and formulate a way to teach it that takes into account the policy directives of state and school and to balance those against the students’ age and experiences. Within the subject of history, this focuses attention on what content to include in a school’s history courses. Much research has also been directed towards the overall perspectives that can and should characterize a particular subject’s content (Evans, 1994; Patrick, 1998; Jarhall, 2012). Less attention has been paid to the relationship between the concept of the discipline of history and the historical narratives that have shaped the way it has been taught. This article, therefore, focuses on the importance of the two concepts so central to history – time and space – and the way they shape the historical narrative and therefore the content of a history course (Wenzlhuemer, 2010; Ritella et al, 2017).

That there are different approaches to time and space within the academic subject of history that affect how historical narratives are constructed, is well documented (cf Braudel, 1977). Different spatial and time perspectives are often applied to history in the fields of history didactics and so-called Big Picture History (Howson & Shemilt, 2011). Within the study of history as a school subject, a great deal of research has been focused on how pupils use time and space to understand their own historicity (van Drie & van Boxtel, 2008; van Boxtel & van Drie, 2012). What has not attracted so much attention until now, is how teachers, from their perspective as historical professionals, choose to combine time and space for a specific teaching situation or course. The two introductory quotations, where two different teachers discuss the content of their teaching on the Middle Ages in very different ways, thus indicate that teaching content is fundamentally determined by a teacher’s decisions regarding the treatment of time and space.

With this principle in mind, this article explores the concepts of time and space so as to identify ways in which teachers make choices related to their teaching. The basis for this is that historical statements and the selection of historical content refer to a certain historical time and a certain historical space. Space is understood here as a geographical place that contains both historical and contextual presuppositions and is reflected in the term ‘historical space’ (in Swedish ‘historiskt rum’) (Magnusson, 1988; Samuelsson, 2005). In wider historical research the term ‘space’ is used both as an object of study, that is to say, as the study of a geographical place with its contextual conditions, and as an observational framework, as a way of theoretically examining and arranging historical content (Wenzlhuemer, 2010, p. 22).

The point of departure in this article is therefore that the content of a historical narrative depends on the combination of time and space. The above statements that Lennart and Linnea made about their teaching, demonstrate that their selection of time and space is a significant part of how historical narratives are constructed. Considering the central position that both time and space have in history, both as a school subject and as an academic discipline, this article seeks to provide an understanding of how these concepts are used by history teachers when creating their teaching content (Massay, 1995; Magnusson, 1988; Wenzlhuemer, 2010, p. 22). The overriding aim of this article, then, is to clarify the concepts of time and space in the teaching content for a course in history (Shulman, 1986; Ball et al., 2008).

Based on that ambition, this article seeks to provide information about the different ways teachers can combine time and space when constructing narratives for history teaching. After a discussion of the existing research on issues in contemporary history teaching, the theoretical framework for this article is outlined. Then follows a more detailed discussion of the article’s aims and some of its research questions.

Deciding on content in a historical narrative: the Swedish example

One of a history teacher’s key roles is to choose teaching content that highlights different historical narratives. Narratives are different understandings of history and how they can be constructed. Research on history didactics has shown that there are a number of ways of formulating a history narrative and that these can result in the selection of different types of history content. For example, Peter Aronsson identifies the “it was better before” narrative (Aronsson, 2004, pp. 79– 84), while Rüsen points out that narratives can be more or less complex in his differentiation between traditional narrative, exemplary narrative, critical narrative and genetic narrative (Rüsen, 2006, p. 72).

The fact that a chosen narrative, therefore, frames the historical knowledge that is to be included in the teaching of history, is apparent in the curriculum documents produced by the Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket), which govern the teaching of history in Swedish schools. As apparent in the quotation below, the Swedish school history narrative has a clearly European chronological orientation that is divided into traditional time periods.

The European classification of time periods from a chronological perspective. Prehistory, Ancient history, Antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment with some areas of specialization. Problematisation of the dependency of historical classification of periods on cultural and political conditions based on specific areas, such as why the term, the Viking Age, was introduced in Sweden in the late 19th century, or comparisons with classifications in some non-European cultures. (Lgr 11, 2011, p. 9)

As the second part of the quote points out, chronological narratives need to be problematized. The Swedish National Agency for Education is making the point that a narrative depends on the context in which it is formulated. They use the example of the Viking period and its construction in the nineteenth century and the fact that historical narratives in other parts of the world might differ significantly from those in Europe. The Swedish school authorities are trying to suggest that the focus on a dominant Western European narrative needs to be problematized.

This quote represents the two perspectives that are recurrent in Swedish research on what is taught in history lessons. Nordgren, for example, describes how most history teaching builds on an underlying Western European narrative that takes the growth and development of the nation state as its starting point (Nordgren, 2006, pp. 204–209). A Western narrative, with its focus on periods such as Antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Enlightenment, tends to dominate, even though teachers often identify the importance of adopting a reflective and critical approach to the dominant narrative by using various competing, even contradictory, narratives (Berg, 2014, pp. 250–252).

A look at the choice of subject content in school courses demonstrates that there too a Western narrative is central (Jarhall, 2012). This is also confirmed in classroom-based case studies by such researchers as Lilliestam, who notes a choice of subject content where the narrative is Eurocentric in character (Lilliestam, 2013). At the same time, studies show attempts to depart from a European narrative by adding curriculum content with intercultural elements (Johansson, 2012). Within the teaching profession in Sweden, there is a growing awareness of a dominant historical narrative, especially when the increasingly ethnic and racial diversity of the student body is likely to have shaped the historical narratives students have had contact with, both inside and outside school (Nordgren, 2006; Samuelsson & Wendell, 2017).

Taken together, the research on Swedish history teaching shows that there exists a tension between the traditional approach, where the historical narrative is clearly defined and Western in its focus, and one where this narrative is, in different respects, problematized and prone to critical review (Rüsen, 2006, p. 72). As professionals, therefore, teachers need to balance both ideological positions when determining the content of their courses. And it is upon this premise, then, that the question is posed of whether or not different ways of combining time and space can help teachers to approach historical narratives in different ways. As the two teachers quoted at the start of this article suggest, choosing a different time and space perspective on the Middle Ages leads to different historical content. This raises interesting questions about how teachers decide to use one or another historical narrative in their teaching.

Previous research on time and space in history teaching and learning

This article is based on the assumption that a subject and its narrative is made up of a number of more or less subject-specific first order concepts (FOCs) and second order concepts (SOCs) (cf Stolare, 2017). These different concepts can be used as tools when history teachers plan and construct the content of a history course (Shulman, 1986; Shemilt, 1983). Both Shemilt, a pioneer in this field, and later on Wineburg, argue that history as a school subject should be based on SOCs, like sourcing and cause and effect, and associated with history as an academic discipline (Shemilt, 1983; Wineburg, 2001). In recent decades, several additional concepts, like historical empathy, have been introduced, often with the argument that these contribute to the identity formation of students and their ability to navigate in a globalized world (Seixas & Morton, 2013).

Within the academic discipline of history, as well as in history education research, the discussion of these historiographical concepts has also included time and space as organizing concepts (Schüllerqvist, 1998; Shemilt, 2000; Somers & Gibson, 1994). For example, within the academic study of history, Braudel and others have long argued that historical issues should be studied across long periods of time, termed la longue durée (Braudel, 1977). Similarly, place has also been discussed as a vital starting point for historical studies, for example in the work of local historians and microhistorians alike (Massay, 1995; Samuelsson, 2005). Much of the research done here involves the study of historical places from a social, economic or political perspective (Magnusson, 1988).

In the study of history education, researchers have also stressed the importance of time and space as organizing concepts (Shemilt, 2000; Somers & Gibson, 1994; Nordgren, 2006; Lévesque, 2008). For example, one theme in the research field is the investigation of how to use timelines to develop historical understanding amongst students. Researchers, like Rüsen and others, have explored how teachers can convey the three periods of time – past, present and future – in history education. They have examined how timelines can be used to develop a sense of time amongst students and an understanding of the connections between events in the past and those taking place now and in the future (Jensen, 1997; Rüsen, 2004; Nordgren, 2006).

Other researchers have shown how the use of chronologies can help to create a contextual understanding of different historical phenomena. Shemilt’s studies, along with those of van Boxtel and van Drie show that chronological lists of when events happened can help students to place historical documents into context. Taken together, these results suggest that time is a vital concept that helps students to understand different historical artefacts in their historical context (van Drie & van Boxtel, 2008; van Boxtel & van Drie, 2012).

In framework-based history teaching, or Big Picture History, time and space are also important concepts (Howson & Shemilt, 2011). For example, Dawson suggests that chronology is not only about events along a timeline, but also about how time, and what is seen to take place during that time, can be scaled up or down in different time periods. Dawson named this a sections framework, which is built upon a certain time period and a certain space (Dawson, 2009). The concept historical epoch, which is also a demarcation of a certain time period and certain space, springs to mind (Jarhall, 2012). However, the missing element in both the framework of the past and the historical epoch approaches is an explicit and displayed relationship between time and space. Both concepts fail to display combinations of time and space that go beyond particular frameworks and specific epochs.

There have been a number of studies that connect, in different ways, the concepts of time and space in history teaching. Much attention has focused on how students manage time and space as they seek to understand history in different ways. With this in mind, this article aims to take a slightly different approach. Firstly, it takes a teacher’s perspective on how to incorporate time and space in teaching content. Secondly, it focuses on time and space as both separate concepts in teaching content and in combination. Thirdly, this article seeks to understand how time and space can be used across a history course as a whole and not just in separate assignments or parts of a course. This article concludes by providing knowledge about teachers’ ways of using different combinations of time and space in a narrative used in a history course.

Theoretical frame: time and space configurations

An important part of teaching is to choose, on the basis of professional judgment, relevant content for different history courses (Shulman, 1986; Berg, 2014). When teachers do that, they choose among possible subject representations, such as narratives, to organize the content for a specific history course. A narrative links together a number of historical incidents which, taken together, are seen as a course of events that take place within a time perspective (Somers & Gibson, 1994; Rüsen, 2004; Nordgren, 2006; Stolare, 2017). The historical narrative is in turn built on a number of underlying concepts that lend narrativity to that historical content (Lee, 2005).

In this context, time and space have been discussed as organizing concepts both in the academic discipline of history as well as in history education research (Schüllerqvist, 1998; Shemilt, 2000; Somers & Gibson 1994; Wenzlhuemer, 2010). Regarding subject syllabi for history, the Swedish National Agency for Education indicates that time and space are important concepts on which to base teaching content. It writes that students should be given the opportunity to “work with historical concepts, questions, explanations and different relationships in time and space to develop an understanding of historical processes of change in society” (Lgr 11, 2011, p. 1). Time and space are thus presented as frameworks in which issues, explanations, connections and concepts are to be studied.

As mentioned above, there are several studies that deal with issues concerning time and space in history education. These concepts are most often studied separately or as aspects of a framework or a period. But as the research coming from a broader educational and history teaching context shows, as well research in global history, there is a need to study time and space in relation to each other (cf Wenzlhuemer, 2010; Ritella et al., 2017). Rather than studying time and space separately, as has been done elsewhere, the focus I have adopted here is on how time and space are combined in history content teaching. Bakhtin uses the concept of chronotope to describe the relationship between time and space in a narrative. Depending on the spatial and time perspectives chosen, a chronotope can assume different configurations, thus adding a specific character to the narrative (Bakhtin, 1981; Ritella et al., 2017).

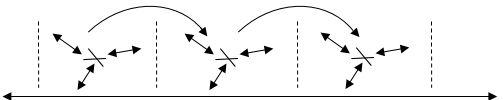

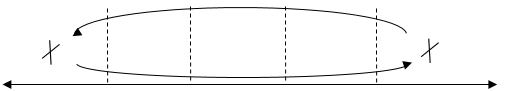

In this article, the different ways of combining time and space in history teaching content are termed time-space configurations (cf Wenzlhuemer, 2010; Ritella et al., 2017). In a time-space configuration, the relationship between time and space in a historical narrative is regulated as in a chronotope. A time-space configuration, therefore, can be described in terms of its geographic place. This could be a continent like Europe, for instance, or an individual country or city, or some other defined geographical location. A time-space configuration can also be described in terms of its social, economic or political situation. For example, the treatment of women or the economic system in a particular geographical place can be the object of study. The time-space configuration can also be extended through time, thus allowing a particular issue to be tracked through devices such as a long timeline, a cyclic event, or the past-present-future perspective. This allows students to grapple with the emergence of Western democracy, for example, or to understand the cyclical nature of economic booms and busts.

Against the backdrop of the research discussed here and the theoretical framework adopted in this article, the aim of this article is, more specifically,

to explore the possibility of identifying different time-space configurations in teachers’ accounts of the history courses they have taught. In doing so, the ambition is to provide different examples of time-space configurations as possible subject-specific tools for teachers to use when determining content and aims for history teaching.

The more precise research questions are:

1/ How can different time-space configurations be identified in the teaching of a unit of history content?

2/ According to the results, how can different time-space configurations be useful for teachers in the process of constructing a narrative in a unit of history content?

Methodological considerations

This is an explorative study aiming to observe if and how combinations of time and space are implemented in a history course. The method used builds on semistructured interviews with teachers, in which the statements that teachers make about their teaching content are analyzed and the different units identified (Esaiasson et al., 2007, pp. 298–301). This means that as many models as possible for thinking about time and space based on teachers’ statements are recorded. Teachers’ statements are then exemplified using assignments from their lessons. Since the study builds on teachers’ statements about their teaching content, every combination of time and space that they suggest must be seen as a potential theoretical model, which can then be exemplified by an assignment from the completed history course (cf Jarhall, 2012). This study is a first attempt to describe if and how these models are operative in teachers’ selection of teaching content. It is a case study in which the empirical examples are examples among a finite number of examples. One argument for this choice of method is the advantage of approaching a previously unexplored issue through interviews with a smaller number of informants. In this way categories can be formulated which can then be tested against studies with a broader methodological approach (cf Schüllerqvist & Osbeck, 2009).

The selection of respondents followed a three-step model. Firstly, a questionnaire survey was distributed to 50 upper secondary history teachers from 14 different schools in a large-sized region in mid-Sweden (cf Evans, 1994). Secondly, individual interviews were conducted with seven teachers to explore their understanding of the purpose and content of the history subject. Thirdly, a second individual interview was conducted with four of the seven interviewed teachers. It was statements made at these second interviews that were analyzed in terms of the conceptual tools used in a history course (Yin, 2009, pp. 3–7). The selection of teachers and schools at each step was built on the variation principle, which was applied to teachers’ background, type of school, geographical dispersion and school governing body. The teachers are not identifiable for ethical and methodological reasons, and their names here are fictive. The participating teachers were aged between 40 and 65 and their teaching subject combinations varied. All of them have been practicing teachers for more than eight years.

Before the interviews, teachers were asked in a telephone call if they would consent to participate in the study and if they met the criterion of teaching a new course for upper secondary history, namely History 1b, during the period of the study. Interviews commenced when this course had reached its halfway point, and were organized throughout its second half. The interviews focused on course content. Prior to the interviews, the teachers submitted examples of their course documentation, comprising descriptions of their course structure, outlines of individual study units and essay questions. About a week before the interviews, a semi-structured interview guide was distributed to the participating teachers. The interview questions were then chosen in order to clarify the detailed content of the course each teacher had constructed and taught. During the interview, questions were asked about the content of the course and its various units and how decisions about how to deliver these had shaped its implementation. Questions were also asked about the documentation the teachers had provided earlier. This was done to ensure that the discussion would be clearly based on the ideas and practices that teachers had adopted for the History 1b course, and not on their approach to history more widely.

All interviews were recorded using an mp3 player and later transcribed. The interpretation of respondents’ answers was done in two steps. First, the transcripts were read through without note taking. Then they were reread to identify as many different combinations of time and space as possible in the teachers’ statements about the History 1b course and its units. Teachers’ statements were then compared – to each other, to previous research, and to meta-concepts – for the purpose of identifying different patterns. This was an inductive process which sought to identify the different ways in which teachers linked the perspectives of space and time together. As a result, three different patterns – categories of time-space configuration – emerged. These categories are described in detail in the results section below, and are illustrated by longer quotes from the teachers themselves. These extracts were then compared with the lesson assignments the teachers had submitted at the time of the interview. In this sense, the study was explorative, building on teachers’ statements and their related course documentation. The object of the study was, in other words, teachers’ statements about a course they were teaching, or had just taught. The combinations of time and space this study has identified, are potential variants that teachers can possibly use when they look to build the content of a course in the future.

Results: Time and space in teaching content

The results of this study, like those reported in other studies, demonstrate that teaching content in history courses is mainly built on a narrative approach to the past, with a focus on European and international elements, and that this appears to be a well-established way of organizing the content of history courses (cf Stolare, 2014; Jarhall, 2012). As we can see from the outlined units in table 1, the Western European narrative in History 1b is dominant, although it is interrupted by units focusing on source criticism, for instance, or ability-related units addressing history usage.

Table 1. Units in the course History 1b taught by the teachers in the study.

|

Lennart’s units: History 1b |

|||

|

Unit 1 |

Unit 2 |

Unit 3 |

Unit 4 |

|

Hunter-gatherer societies. Characterized. |

First agricultural societies. Political, social issues. |

Ancient Greece. Politics and Culture. |

Middle Ages. Early Middle Ages and High Middle Ages. |

|

Unit 5 |

Unit 6 |

Unit 7 |

Unit 8 |

|

Early modern time. Agency. |

The time of great Swedish power. Agency, politics. |

Revolutions. Comparison between revolutions. |

World War, Cold War. Cause and effect. |

|

Anders’ units: History 1b |

|||

|

Unit 1 |

Unit 2 |

Unit 3 |

Unit 4 |

|

Agriculture from early civilization to the new era. |

The time of great Swedish power. |

French revolution. Perspectives on history. |

Ideologies as nationalism. Different explanations. |

|

Unit 5 |

Unit 6 |

Unit 7 |

Unit 8 |

|

From war to war. Source criticism and the use of history. |

The holocaust with a focus on cause and effect. |

Sweden in the nineteenth and twentieth century. |

The use of history. History in music and museums. |

|

Karin’s units: History 1b |

|||

|

Unit 1 |

Unit 2 |

Unit 3 |

Unit 4 |

|

Source criticism. Analysis of newspaper articles. |

Analyze a historical person’s life in their historical context. |

Democracy, ideologies, Swedish political parties. |

Historical periods to 1700. Soc/pol/cult/eco aspects. |

|

Unit 5 |

Unit 6 |

Unit 7 |

|

|

Nationalism, industrialization and colonization. |

Source criticism and criteria for source criticism. |

Identity issues. Your own identity. |

|

|

Linnea’s units: History 1b |

|||

|

Unit 1 |

Unit 2 |

Unit 3 |

Unit 4 |

|

Ancient Greece. Democracy, human values. |

Middle Ages. Labor, legal justice, human values. |

The time of great Swedish power. Politics. Swe-Finland. |

Revolutions. Industrial America. Emergence of ideologies. |

|

Unit 5 |

|

|

|

|

Welfare state. Social engineering. Voting rights. |

|

|

|

Source: Teachers’ Planning – History 1b, Academic year 2011/2012

When a further detailed study of the evidence was carried out and related to each of the 28 different units, this revealed that the historical representation, and by extension the historical narrative, was organized differently depending on the choice of time and space. In the next sections, a more detailed analysis of the three main ways these teachers combined time and space into time-space configurations on the History 1b course is presented. First, the common patterns in the different ways of combining time and space categories are described. Second, on the basis of the empirical material presented here, some preliminary suggestions as to how combining time and space can serve as an organizing concept in a narrative and history teaching context, are discussed.

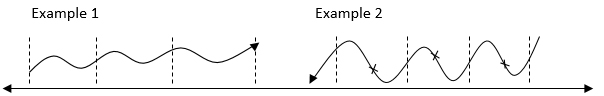

Time-space configurations from past to present

The first category of combining time and space that emerges from the teachers’ statements is teaching content with a clear chronological order and a relatively defined historical time period and location. This time perspective has a clear logic of ‘before to now’, and history is studied chronologically from the past to the present. The time periods are clearly demarcated from each other in different units. The historical spaces used are frequently located to specific geographical places. This category breaks down into two different time-space configurations.

The most common time-space configuration in this category has a chronological order where time is divided into consecutive periods. When using this model, different issues are studied separately and then cross-sectionally. Answers are sought to the question: What has changed from one period to another?

In this configuration, the historical spaces are geographically demarcated and the issues are studied in specific geographical places. In the following example, taken from the teacher Karin’s fourth unit, the students used Greece as a case study of Antiquity, concentrated on Central Europe in the Middle Ages, and examined the Enlightenment through a French lens. For each time period and for each country they studied, they considered the political, economic and social issues.

Power and politics, and then we looked at how power is distributed and shifted. Democracy, the concept. Culture and religion, and then social conditions with a focus on class differences and women’s situation. Also, how they made a living, or what the economy was like in each period. Those were the four focus areas based on the questions we had. Then we had joint discussions on what changed and what distinguished one period from another. A kind of comparison across periods. What changed and what is happening?

(Interview Karin)

The next stage of this unit was to compare the mappings they had made of the different time periods to see if there were any changes between them. Continuity and change emerged as important SOCs when the periods were compared in terms of similarity and difference.

The second time-space configuration within this first category also involves following issues in chronological order from the past to the present. A characteristic feature here is that time is divided into consecutive periods with a focus on changes within different issues during each period.

Spaces are once again primarily connected to geographical places. These are selected for study because they demonstrate what the teacher thinks are “typical features” of the time period. In the example below, the teacher Lennart discusses his unit on Antiquity and the Roman Empire and what he felt was important to cover when linking this period to the next unit on the Middle Ages.

And then we talk about the causes of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. We touch on weak states and the robber economy and things like that. The extremely unstable situation leading to migrations and small wars and general insecurity. Here I can include things on the importance of relatively strong states and state formations where people know what they have to conform to. I also try to compare this to the situation when they get too strong and turn into despotic and oppressive societies. The next thing we cover is the typical features of the early Middle Ages and how it turns into the early modern period when nation states stabilize. We also look at the causes a bit – of rise and fall. What caused the rise of the Middle Ages? Stability, climate change and other things increased production. And then we also look at communities in the Late Middle Ages when the effects of the plague had abated and what happened then.

(Interview Lennart)

Table 1 shows that Lennart taught units 3 and 4 in the History 1b course, where different issues concerning changes in political and economic situations and in government were studied in different geographical places, especially in Europe. This time-space configuration requires the use of the SOCs continuity and change, cause and effect, rise and fall, and stability and instability.

As an example of this approach to time and space we can see from Lennart’s lesson assignments that his focus was on the characteristics of Antiquity and the Middle Ages, where different questions changed over time. The questions he and his students addressed were as follows:

1/ Approximately when did the Late Middle Ages begin? When did they end?

2/ What was the reason for population decline during this time? When was the Black Death?

3/ What percentage of the European population is estimated to have succumbed to the Black Death?

4/ What explanation did people in the Middle Ages give for the Black Death?

5/ After the Black Death, the lives of farmers actually improved: how can this be explained?

6/ In what way were improvements for farmers evident?

7/ The power of the monarchy increased during the Late Middle Ages, at the cost of feudalism. Explain how!

8/ In which year did William the Conqueror invade England and enjoy a decisive victory at the Battle of Hastings? (You will need to return to the start of the High Middle Ages.) 9/ In what way did this set the backdrop for the Hundred Years’ War between France and England?

(Lennart’s lessons)

These questions are also characteristic of the ones Lennart discusses in his units on Antiquity and the Middle Ages. For him, the historical space is Western European and the questions posed are mostly about such themes as economics and politics: for example, the economic status of farmers or the change in the power of the monarchy within the political system. What is notable, is that the time perspective he adopts is demarcated into three ages: The Early Middle Ages, the High Middle Ages and, in this case, the Late Middle Ages.

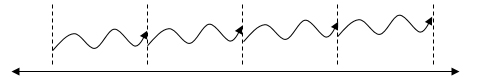

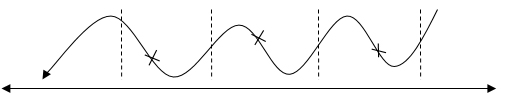

Time-space configurations across long time periods

The second category of time-space configurations involves working on a question or a theme from a long time perspective. Once again, two typical approaches can be identified. The first approach to time-space configuration in this category involves following the development of a question from past to present, but with a future perspective. In this perspective, the historical spaces were chosen because of their relevance to the question.

In the example below, which refers to a time towards the end of the teacher Anders’ unit 7, the task was to study gender issues across several time periods, combined with a prognosis of how this issue would manifest itself in the future.

We had to consider men and women in the past and now, and then students were expected to look ahead. There was a lot about the status of women and the relationship between the sexes. Rights and things. Then I had a text, a good text that I uploaded to their computers and where there was more support to move forward.

(Interview Anders)

The spatial perspectives in this approach were not always sequenced chronologically. There was no particular geographical focus; it was the question that determined where the focus of study should be. To clarify change around the question of gender relationships, the concepts of men and women’s rights were used. In this example, comparison was important since structural gender relations were displayed, making the concepts’ similarity and difference operative organizing concepts.

The second approach to time-space configuration in this category also involves following the development of an issue from a long-term perspective; however, the geographical places are chosen based on how they might illustrate the issue at hand. Here it is the time perspective that keeps the time-space configuration together, while the historical spaces are less important and are subordinated to the linear perspective. Following the development of an issue or theme over a long period of time can reveal the cyclical nature of the issue.

For example, Anders talked about how he covered the changes taking place within farming and agriculture, from the early river cultures to the Middle Ages.

And about agriculture, the idea was that students should … there was something in the textbook where they should … I don’t remember the instructions I gave – I usually write something to guide them. I thought, what has changed and how has it changed? What is the driving force? Who slows things down? Is someone holding it back? In short, the questions focused on what drives development and change.

(Interview Anders)

This unit (on long-term agricultural change) came at the beginning of Anders’ teaching of History 1b. The historical and geographical spaces were chosen to say something about the question. Above all, in this combination of time and space, we can see that the long timelines are determined by the question, and the historical spaces, which happen to be European, are downplayed. The study of agricultural change has an emphasis on the causes of change and factors contributing to stability.

If we look at the examples of time-space described by Anders above, about the changes to agricultural practices over time, we can see a similar emphasis in his lesson descriptions on long-term perspectives from prehistory to the Middle Ages, without any real demarcations in terms of specific time periods. The focus is on the changes and their causes, and what their effects were.

Assignment:

Describe developments in agriculture between prehistory and the Middle Ages. How was farming done? In what ways did it change? Reasons for the changes? Effects of the changes (=consequences)?

Worth considering:

Farming methods, tools, implements, technology, land ownership, household economy and living conditions, taxes, feudalism, Black Death.

NOTE: As the examples above show, there were factors that were not directly related to agriculture that affected it – such as the Black Death. Remember, these are just examples; there may be others.

(Lesson assignment, Anders)

The perspective of change that is used in this material is tied to certain specific themes or issues, such as agricultural technology, the household economy or the economic foundations for social or political systems. Here there is room to choose a certain aspect on which to focus, and a reminder that some aspects can affect one another: for example, the Black Death can have a significant impact on agriculture and vice versa. In this time-space configuration, as Anders’ assignment shows, questions about place are given little emphasis. Looking at his course plans, though, an international perspective becomes apparent even if Europe is the focus.

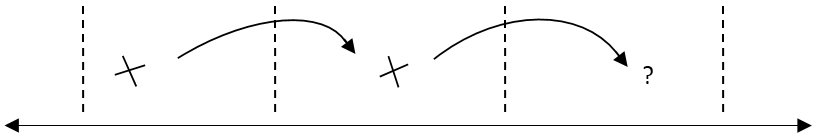

Time-space configurations with a shifting choice of time and place perspectives

The third category of time-space configuration differs from the previous two because it involves comparison. Comparison is a central component of historical analysis; it encompasses comparison between time periods as well as historical spaces. In this time-space configuration, unlike the previous two categories, the time perspective can shift between ‘then to now’ and ‘now to then’. The teachers’ statements and their teaching materials also incorporate two variants of this third time-space configuration. The first example involves the comparison between a phenomenon in the present (or the past) and in a specific historical space with one in the past (or in the present). The present (or the past) is studied with the help of a reference from its historically opposite period.

Taken from Linnea’s first unit in the course, this example involves comparing circumstances in ancient Greece with the present day. Here is the teacher’s description of the unit:

They were also expected to find phenomena in Greek society which still existed and to reflect on whether these mean the same today as they did then. This was a sports class, so the Olympic Games came up.

(Interview Linnea)

In this case, the comparison involved the original Greek games, established in ancient times, and the current Olympic games. A contemporary manifestation was thus used to illustrate a historical phenomenon. Working the other way around, students were also being asked to trace the development of a current issue back to a particular point of reference in history. Modern times were thus contrasted with the situation in Ancient Greece. The central concepts in this example are similarity and difference along with continuity and change.

The second way of comparing different issues across historical space was to reverse the time perspective; that is, to compare an issue or problem from the present and look for examples back in time.

Historical spaces can contribute to an explanation of a contemporary question. The example below centers on current political ideologies and the historical spaces that were unimportant in their construction. The spaces studied were therefore unimportant and determined by the issue studied.

Yes, if I take the example of ideologies. We worked together in this class where I taught civics and history, so it was quite easy. There were a number of course objectives related to politics and ideology and development. We started with the students and their interest in ideology. They thought about it and those who were interested in feminism were asked to start thinking about what it had been like in the past, when it emerged and why. They had many ‘Aha’ experiences.

(Interview Karin)

This approach meant taking present-day political issues, such as gender, and using them to study the different historical periods in which these ideologies were developed. The space was mainly European. It is clearly evident that the study of the time-space configuration in this way relies on the concepts of continuity and change to investigate an issue back through time. It includes a question of why, which indicates various causal explanations.

This time-space configuration is evident in Karin’s instructions for the lesson, which begin by asking students to look at the question of equality in relation to political parties and their ideological roots.

Ideologies:

-

- Liberalism

- Conservatism

- Socialism

- Communism

- Anarchism

- Feminism

We chose to divide the class into six groups: each was to focus on one specific ideology. They then had to explain them to the others in the class, using, for example, PowerPoint presentations. How they delivered their explanations was up to them to decide, but they had to consider how the other groups would best understand the material they were summarizing.

Research Questions:

When were the ideologies developed?

What does each ideology stand for? What is its intention? What does it prioritize? Which of the Swedish parties holds with which ideology?

How are politics affected by ideologies? How can you tell which ideological basis a party has?

The number of followers it has? How is equality viewed?

(Lesson assignments, Karin)

Karin’s approach begins in the present with a decision about what issue is to be studied. In this case she wanted students to examine the issue of equality from the perspective of different political ideologies and the Swedish political parties who adhere to them. Several of the questions asked students to reflect on how equality is treated today. When this was done, the exercise then involved looking back at the past to examine the historical context in which these ideologies were established. With this approach, the time-space configuration starts in the present, by considering issues and ideas in their contemporary context. Once the issue in its present circumstances is understood, students are then invited to examine the historical context in which these ideologies were formed. In this way, Karin’s students were encouraged to examine the origins of political ideologies and the historical circumstances that gave rise to them.

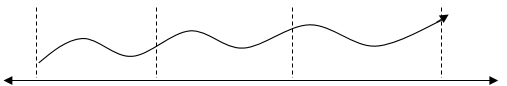

Conclusions: Time-space configuration in teaching content

To summarize, this study has shown that different combinations of time and space have an impact on how the historical content of a history course is organized. More than anything else, two different actions tend to generate time-space configurations. The first involves selecting both time and space perspectives. By using a specific way of handling time in teaching in relation to a selection of spatial perspectives, content will assume a unique character. This is evident in the first two quotes cited in this article where various ways of handling time and space in relation to a unit on the Middle Ages greatly affected the historical content.

This means that a teaching unit where the focus is on similar historical spaces, can come to have completely different content depending on how time and space are linked. For example, one of the teachers used the concept of successive historical time periods to study social change in a European perspective. In such a scenario, the historical spaces became examples of how different issues changed over time. By focusing on similar periods not necessarily in consecutive order, another teacher was able to use the individual time periods for comparative purposes. Each period was studied separately on the basis of its character and was then compared over time to identify similarities and differences, and also, in this case, to illustrate continuity and change. Conversely, a shifting time perspective affects historical space.

The second influence on the character of time-space configurations is the decision to place time or space in the foreground or background. Emphasis on one or the other shifts its presence in a lesson and creates different content. Consider, for instance, the example when one of the teachers described how he approached agricultural change across a long time period. The spaces used became secondary. Beyond the issue studied, historical space was hardly mentioned. The point was the change in time. Likewise, when space was foregrounded, time became less important. This is clear in the example of the Middle Ages and the labor market in Stockholm. Here the focus was on the actors and their relation to the spatial conditions of the community. The time perspective was constituted by the specific historical space and its time-dependency in a greater chronological perspective. Other examples show that the relation between time and space can also be more evenly balanced.

The results show that time-space configurations occur at all levels of a teaching lesson: in individual assignments, course units and the conceptualization of a course as a whole. It should be noted that the selected time and space categories, like the concepts of continuity and change, can go beyond the specific teaching content (Seixas & Morton, 2013). This pattern is also typical in the academic study of history, where long time periods and cyclical courses can continue well beyond specific epochs (Braudel, 1977). We can also see how transcending historical periods can shape a whole unit, such as the one on political ideologies and their backgrounds considered earlier. The content of the course as a whole seems, in the teachers’ accounts, to be organized on the basis of time and space categories that fall within a historical period as well as going beyond it. Different combinations of time and space thus inform the content of the course in a pervasive way.

Discussion: findings and contribution to practice

The aim of this article has been to identify different time-space configurations in history teachers’ accounts of their taught courses. In doing so, the ambition was, by providing different examples of time-space configurations, to suggest different tools for teachers to use when constructing content for history teaching. This study has identified several ways in which time and space can be combined in history teaching. Before discussing these results it should be stressed that these examples of time-space configurations should be seen as only potential and theoretical constructions for how time and space could be combined in a history lesson. The generalizability of these configurations is empirically limited. The results of this study are based on statements taken from a particular set of teachers working on a particular history course, and through their provision of a particular set of teaching materials.

That said, the results are supported by the theoretical frame of the study. That time and space categories are central in historical exposition, can be related to Bakhtin’s argument that the time-space relationship in a narrative and the selection of historical content are determined by how time and space are combined (Bakhtin, 1981). Like a chronotope, a time-space configuration in a history teacher’s work can be shaped by its geographical space. For example, the study of the European geographical space can be determined by a teacher’s concentration on its political and economic conditions, as one of the cases mentioned above. The geographical space can then be studied in line with the chronotope and, as the example shows, through political and economic timelines or cycles.

With these conclusions in mind, I suggest that the six time-space configurations identified in this study can be used to help teachers select their historical content. Time-space configurations place different emphases on the historical narrative around which the teaching content is usually based. For example, a teacher can choose to stress the issue of change over a long period of time, where the distinctions between historical time periods and the references to historical space are downplayed. Teachers can choose to apply this approach forwards, from the past to the present, as was done in the treatment of agricultural change in this study.

Significantly, it was the concepts of cause and effect which determined this choice of time-space configuration. Equally, teachers can choose to apply this long time approach backwards, from the present to the past. When teaching feminism, for instance, the question was posed from a contemporary perspective that looked back in time. Historical time period and geographical place were equally disregarded. And once again, the concepts of cause and effect, as well as continuity and change, were the underlying concepts. Although the overriding narrative was the same, the teachers’ decisions to combine time and space in particular ways meant that they generated different historical content. Different time and space decisions therefore generate different teaching content.

While these time-space configurations can serve a practical purpose in the classroom, recognizing their existence can also contribute to wider debates about how history should be taught at school. Research on the teaching of history has identified several positions that teachers adopt when they formulate the aims and content of their teaching. Depending on how teachers balance their course content, the purpose and goals of the course are differently constructed (Berg, 2014; Jarhall, 2012;Persson, 2019). For example, if teachers choose an international spatial perspective, focusing on political issues in combination with a long-term linear time perspective from the past to the present and divided into different time periods, then the content will assume a certain character and correspond with certain goals. If teachers choose a local spatial perspective, focusing on individual identities and social issues in a short-term perspective from the past to the present, the content will have a completely different character and achieve very different goals. The different ways of combining time and space in different time-space configurations have, therefore, the potential to reflect different ways of understanding the purpose and point of the history subject.

With that in mind, individual teachers and teachers working in teams can use their awareness of time-space configurations to discuss how they could both diversify their approach to the content of their courses and by extension, their delivery of the history subject. An important aspect of the research conducted here is that the time-space configurations that the teachers presented were designed in relation to an existing course and to the broader subject requirements drafted by the Swedish educational authorities (Shulman, 1986). Considering this, I propose that the time-space configurations identified in this study provide a useful conceptual apparatus that teachers can use in planning, implementing and evaluating teaching, both individually and in collegial interaction. The results of the study also have the potential to contribute to the theoretical discussion surrounding the disciplinary concepts that can and should be used in history teacher education.

References

Interviews

Interview Karin. February 2, 2012

Interview Lennart. April 2, 2012

Interview Linnea. April 23, 2012

Interview Anders. April 27, 2012

Teachers’ planning: History 1b, academic year 2011/2012

Lesson assignments: History 1b, academic year 2011/2012

Dates when documents were received from the teachers:

Karin. January 24, 2012

Lennart. March 21, 2012

Linnea. April 10, 2012

Anders. April 18, 2012

Litteraturhenvisninger

Aronsson, P. (2004). Historiebruk: Att använda det förflutna [Use of history: To use the past]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The Dialogic Imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Ball, D. L., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108324554

Berg, M. (2014). Historielärares ämnesförståelse: Centrala begrepp i historielärares förståelse av skolämnet historia [History teachers’ subject conceptions: The conceptual construction of history in school]. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

Braudel, F. (1977). La longue durée [The long term]. In F. Braudel (Ed.), Écrits sur l’histoire [On history] (pp. 41–83). University of Chicago Press.

Dawson, I. (2009). What time does that tune start? From thinking about “sense of period” to modelling history at Key Stage 3. Teaching History, 135, 50–57.

Esaiasson, P., Gilljam, M., Oscarsson, H., Towns, A., & Wängnerud, L. (2007). Metodpraktikan: Konsten att studera samhälle, individ och marknad [Metods in science: To study society, individuals and market]. Vällingby: Elanders Gotab.

Evans, R. W. (1994). Educational ideologies and the teaching of history. In G. Leinhardt, I. Beck, & C. Stainton (Eds.), Teaching and learning in history (pp. 171–208). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Howson, J., & Shemilt, D. (2011). Framework of knowledge: Dilemmas and debates. In I. Davies (Ed.), Debates in History Teaching. London, Routledge.

Jarhall, J. (2012). En komplex historia: Lärares omformning, undervisningsmönster och strategier i historieundervisningen på högstadiet [A complex history: Teachers’ transformation, teaching patterns and strategies in history teaching in lower secondary school]. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

Jensen, B. E. (1997). Historiemedvetande begreppsanalys, samhällsteori, didaktik [Historical consciousness concept, theory, didactics]. In C. Karlegärd & K.-G. Karlsson (Eds.), Historiedidaktik [History didactics] (pp. 48–81). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Johansson, M. (2012). Historieundervisning och interkulturell kompetens [History teaching and intercultural competence]. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

Lee, P. (2005). Putting Principles into Practice: Understanding History. In S. Donovan & J. Bransford (Eds.), How students learn: history, mathematics, and science in the classroom (pp. 31–78). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Lévesque, S. (2008). Thinking historically: Educating students for the twenty-first century. Toronto: Buffalo.

Lgr 11 (2011). Ämnesplan för historia, gymnasiet [Curriculum for history in upper secondary school]. Skolverket. https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.4fc05a3f164131a7418105c/1535372297799/Hist ory-swedish-school.pdf

Lilliestam, A.-L. (2013). Aktör och struktur i historieundervisningen: Gymnasieelevers historiska tänkande [Agent and structure in the history classroom. About the development of students’ historical reasoning]. Göteborg: Ale Tryckteam AB.

Magnusson, L. (1988). Den bråkiga kulturen: Förläggare och smideshantverkare i Eskilstuna 1800–1850. [The unruly culture: Publishers and forging craftsmen in Eskilstuna 1800– 1850]. Stockholm: Författarförlag.

Massay, D. (1995). Places and their pasts. Historical workshop journal, 39, 182–192.

Nordgren, K. (2006). Vems är historien? Historia som medvetande, kultur och handling i det mångkulturella Sverige [To whom does history belong? History as consciousness, culture and action in multicultural Sweden]. Karlstad: Karlstads universitet.

Patrick, K. A. (1998). Teaching and learning: The construction of an object of study. Centre for higher education, The University of Melbourne.

Persson, A. (2019). Kolonisatör eller turist?: Frågor och arbetsuppgifter i svenska historieläromedel under en tid av kunskapsideologisk förhandling [Coloniser or tourist?: Questions and exercises in Swedish history textbooks during a period of ideological negotiating]. Nordic Journal of Educational History, 6(2), 45–72.

Ritella, G., Ligorio, M. B., & Hakkarainen, K. (2017). Theorizing space-time relations in education: The concept of chronotope. Frontline Learning Research, 4(4), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v4i1.210

Rüsen, J. (2004). Historical Consciousness: Narrative Structure, Moral Function, and Ontogenetic Development. In P. Seixas (Ed.), Theorizing historical consciousness (pp. 63–85). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Canada.

Rüsen, J. (2006). History: narration, interpretation, orientation. New York: Berghahn Books.

Samuelsson, J. (2005). Kommunen gör historia. Museer, identitet och berättelser i Eskilstuna 1959–200 [The municipality invents history. Museums, identity and narration in Eskilstuna 1959–2000]. Stockholm: Erlanders Gotab.

Samuelsson, J., & Wendell, J. (2017). A national hero or a Wily Politician? Students’ ideas about the origins of the nation in Sweden. Education 3–13, 45(4), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2015.1130077

Schüllerqvist, B. (1998). Tidsuppfattningar: Några teman i historisk och sociologisk litteratur om tiden [Perceptions of time: Some themes in historical and sociological literature on time]. In S. Bengt & S. Lilja (Eds.), Perspektiv på tiden [Perspective on time] (pp. 37– 58). Gävle: HS institutionen.

Schüllerqvist, B., & Osbeck, C. (2009). Ämnesdidaktiska insikter och strategier – berättelser från gymnasielärare i samhällskunskap, geografi, historia och religionskunskap [Subject didactic insights and strategies – stories from high school teachers in social studies, geography, history and religious studies]. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

Seixas, P., & Morton, T. (2013). The Big Six: Historical thinking concepts. Toronto: Nelson Education.

Shemilt, D. (1983). The Devil’s Locomotive. History and Theory, 22(4), 1–18.

Shemilt, D. (2000). The Caliph’s Coin: The Currency of Narrative Frameworks in History Teaching. In P. N. Stearns, P. Seixas, & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, Teaching and Learning History. National and International Perspectives (pp. 83–101). New York: New York University Press.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching? Educational researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

Somers, M., & Gibson, G. (1994). Reclaiming the Epistemological ‘Other’: Narrative and Social Constitution of Identity. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Social Theory and the Politics of Identity (pp. 35–98). Oxford: Blackwell.

Stolare, M. (2014). På tal om historieundervisning: Perspektiv på undervisning i historia på mellanstadiet [On the subject of history education: Perspective on history education in upper primary school]. Acta Didactica, 8(1), Art. 9. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.1101

Stolare, M. (2017). Did the Vikings really have helmets with horns? Sources and narrative content in Swedish upper primary school history teaching. Education 3–13, 45(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2015.1033439

van Drie, J., & van Boxtel, C. (2008). Historical Reasoning: Towards a Framework for Analyzing Students’ Reasoning about the Past. Educational Psychology Review, 20, 87– 110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-007-9056-1

van Boxtel, C., & van Drie, J. (2012). “That’s in the Time of the Romans!” Knowledge and Strategies Students Use to Contextualize Historical Images and Documents. Cognition and Instruction, 30(2), 113–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2012.661813

Wenzlhuemer, R. (2010). Globalization, communication and the concept of space in global history. Historical Social Research, 35(1), 19–47. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.35.2010.1.19-47

Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: design and methods (4th ed.). London: SAGE.