Praktisering av kritisk visuell literacy i engelskundervisningen i norske videregående skoler: muligheter og utfordringer

Hva betyr det å være lesekyndig i dag, og hvordan kan utdanningen forberede elever på å navigere i et stadig mer komplekst tekstmiljø?

Denne artikkelen utdyper muligheter og utfordringer i sammenheng med å gjennomføre kritisk visuell literacy (på engelsk critical visual literacy (CVL)) i engelskfaget i norske videregående skoler som en måte å forberede elevene på å møte kompleksiteten og mangfoldet i dagens tekstlandskap. Studien bygger på et doktogradsprosjekt som setter søkelyset på meningsskapende prosesser blant elever når de diskuterer bilder med utgangspunkt i et interkulturell læringsperspektiv, og utvider dette ved å gi stemme til de deltakende elevene og lærerne. Data bestod av feltnotatene til forskeren og svar fra elever fra en 16-ukers lang intervensjon der 83 elever i norske videregående skoler ble introdusert for CVL som en integrert del av engelskundervisningen. Ved å bruke tematisk analyse, ble dataene analysert med søkelyset på muligheter og utfordringer som oppstod blant lærere og elever da de praktiserte CVL i engelskundervisningen. Tre temaer ble identifisert og diskutert; «endring av praksis i klasserommet», «samskapingsprosesser» og «lesing og samtale om bilder».

Enacting Critical Visual Literacy in Norwegian Secondary School EFL Classrooms: Opportunities and Challenges

What does it mean to be literate today and how can education prepare learners to navigate a increasingly complex textual environment?

This article elaborates on opportunities and challenges related to implementing critical visual literacy (CVL) in English as a foreign language (EFL) classrooms in Norwegian secondary schools as an approach to preparing learners to face the complexity and diversity of today’s textual landscapes. The study draws on a doctoral research project which focused on the meaning-making processes learners engage in when discussing images from the perspective of intercultural learning and expands on this by giving voice to the participating students and teachers. Data consisted of researcher field notes and learner responses from a 16-week intervention in which 83 upper secondary EFL learners in Norway were introduced to CVL practices as an integrated part of their EFL classes. Using thematic analysis, the data was analysed with a focus on the opportunities and challenges that arose from teachers and learners enacting CVL in the EFL classroom. Three themes were identified and discussed, including ‘Changing classroom practices’, ‘Co-construction processes’ and ‘Reading and talking about images’.

Introduction

The aim of the current article is to outline some opportunities and challenges related to the enactment of critical visual literacy (CVL) in English as a foreign language (EFL) classrooms in Norwegian secondary schools. Today’s world is becoming increasingly complex, with social and economic developments increasing intercultural mobility and communication. This trend is further enhanced through digital technologies, which provide access to content created in a large variety of global contexts. Importantly, this content is more often than not multimodal, and a large amount of the information and ideas are communicated through visual images. For example, the most-used social media channels among Norwegian youth, Snapchat, YouTube, and TikTok (Medietilsynet, 2022), all rely heavily on the visual mode of communication. This begs the questions of what it means to be literate today and how education can prepare learners to navigate this increasingly complex textual environment.

Going back to the 1990s, the New London Group argued that the fundamental purpose of education must be ‘to ensure that all students benefit from learning in ways that allow them to participate fully in public, community, and economic life’ (New London Group, 1996, p. 60) and highlighted the fundamental role of literacy in achieving this. To participate in an increasingly culturally and linguistically diverse world, which since then has become even more complex, they argued that the traditional approach to literacy as ‘teaching and learning to read and write in standard forms of a national verbal language’ was not sufficient (New London Group, 1996, pp. 60–61). Instead, they proposed a pedagogy of multiliteracies, where literacy is understood not as singular, but as plural, and not as ideologically neutral, but as socially and culturally situated.

Located within this extended view of literacy, CVL is an approach to teaching which facilitates learners’ engagement in literacy practices that emphasise the social, cultural and ideological contexts of images. It places particular emphasis on visuals as an important meaning-making resource in society, not just because of their extended role as a mode of communication enabled through new technologies, but also because they are particularly persuasive. As Sherwin (2008) argues, unlike verbal texts, which are more obviously constructed by the speaker or writer, ‘images appear to offer a direct, unmediated view of the reality they depict’ and, as such, people tend to see images, and photographs in particular, as ‘credible representations of […] reality’ (p. 184). Consequently, despite the fact that people are surrounded by images and construct meanings from them in their daily lives, they do not ‘naturally possess sophisticated visual literacy skills’ (Felten, 2008, p. 60).

CVL is based on the principle that all images, photographs included, are constructed in the sense that image-makers have to make a number of choices regarding how they will represent the world (Janks et al., 2014). These choices may be conscious or subconscious, intentional or coincidental, but regardless of this, they can never be neutral (Janks, 2010). Instead, the choices act together to create a position for the viewer: a particular way of viewing the world. What CVL does, then, is to engage learners in literacy practices which aim to make the workings of images conscious (Newfield, 2011, p. 92), so that they can make more informed choices in their response to the positions on offer. Studies have found that Norwegian secondary learners struggle to identify the ways in which multimodal advertisements in social media are constructed to persuade (Undrum, 2022) and pay little attention to images when evaluating commercial texts (Veum et al., 2022), suggesting the necessity to implement such literacy practices in Norwegian classrooms.

Although CVL is not explicitly mentioned in the English subject curriculum in Norway, the curriculum does encourage approaching literacy as multimodal and socially and culturally situated. In relation to multimodality, it is stated that ‘texts’ as a term is understood in a broad sense and ‘can contain writing, pictures, audio, drawings, graphs, numbers and other forms of expression that are combined to enhance and present a message’ (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019, p. 3). Moreover, the development of reading skills in English is outlined as ‘being increasingly able to critically reflect on and assess different types of texts’ (p. 4), indicating a literacy focus which goes beyond decoding and comprehending. Finally, the curriculum emphasises the potential of intercultural learning through literacy practices, stating that by working with English-language texts in a reflective, interpretative and critical manner, the learners ‘shall acquire language and knowledge of culture and society’ which, in turn, will help them ‘develop intercultural competence enabling them to deal with different ways of living, ways of thinking and communication patterns’ (p. 3).

While critical literacy has gained more ground in the Norwegian context over the past few years (Normand et al., 2022), there is no long tradition of utilising it as a teaching approach and the research base is small within the Norwegian context (Veum et al., 2021). Consequently, very little is known about how CVL can be enacted by teachers and learners in the Norwegian EFL classroom and the opportunities and challenges that arise from this. The current article seeks to address this research gap by drawing on data collected in relation to a doctoral research project which sought to explore the meaning-making processes that upper secondary EFL learners in Norway engage in when reading images from the perspective of intercultural learning before and after being introduced to CVL practices (Brown, 2021a). Expanding on this project, the article draws on a combination of researcher field notes and learner responses, data previously not reported on, to present teachers’ and learners’ voices on the opportunities and challenges CVL affords in the Norwegian EFL classroom.

Theoretical and empirical background: What does CVL as an approach to literacy in the EFL classroom entail?

The theoretical foundation for introducing CVL in the EFL classroom as conceptualised in the current study is grounded in a social semiotic view of communication, wherein all meaning-making is viewed as socially and culturally situated. From this perspective, the process of meaning-making involves selecting from a range of meaning-making resources, the potential meanings of which are learned through and shaped by meaning-making practices within certain social and cultural contexts (Kress, 2010). An author’s choice of meaning-making resources will be driven by: (1) their interpretation of what different meaning-making resources mean, and how and when they should be used; (2) their desire for their message to be understood; and (3) their interests, i.e., what exactly they want to communicate and/or what they want to gain from the communication (Kress, 2010). Likewise, a reader’s interpretation of the message provided by the author will be driven by their understanding of the meaning-making resources and their interests, which may or may not align with the author’s.

Scholars who have explored a social semiotic view of meaning-making in the language-learning context, such as Kramsch (1993) and Kearney (2016), have argued that if meaning-making is seen as a social practice, then culture must be placed at the very core of language teaching. In other words, culture cannot be taught as a separate entity from meaning-making but must be seen as both being shaped by and shaping all communication (Kramsch, 1993). Because interests are at play in communication, meaning-making must not be treated as ideologically neutral but should be understood as the process of selecting resources from a range of options and ‘doing so purposefully to establish, negotiate or advance a perspective’ (Kearney, 2016, p. 4). From this point of view, intercultural learning can be seen as involving the development of the ability to understand and purposefully employ the meaning-making resources through which communication happens in a variety of cultural contexts (Brown & Alford, 2023). This requires the resources to be brought to the surface, from unconscious to conscious, and that learners are given tools to critically evaluate their own interpretations rather than resorting to assumptions.

The process of meaning-making is developed through years of socialisation and therefore often appears to be ‘natural’ and ‘normal’. Thus, the challenge for EFL learners is to develop awareness of the fact that their own and other’s meaning-making processes are indeed socially and culturally situated. I will suggest that an opportunity for addressing this lies in literacy practices.

Critical visual literacy practices and their relationship to intercultural learning

CVL is an approach to teaching that facilitates learners’ engagement in literacy practices which emphasise the social, cultural and ideological contexts of images. That is, by providing analytical tools, specific approaches to reading and producing images, and guiding questions, CVL aims to facilitate learners’ willingness and ability to engage with such literacy practices.

CVL can be said to be a subfield within critical literacy, focusing specifically on the visual image as an important mode of communication. The wider field of critical literacy is complex and diverse and has, since Freire’s (1993) work on critical pedagogy, first published in 1970, developed through and drawn on multiple critical traditions, including the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory, feminist, postcolonialist and poststructuralist theories, cultural studies, and critical linguistics (Luke, 2014). Scholars warn against narrow and prescriptive views of critical literacy, arguing for the need to situate such practices in local contexts and allow individual backgrounds and reactions to work as a starting point for inquiry (e.g., Lau, 2015; Luke, 2014). With this in mind, the current study draws on Lewison et al.’s (2002) model of the four interrelated dimensions of critical social practices. The model is widely used in second and foreign language settings and provides general guidelines without being too prescriptive. In the following, the four dimensions will be discussed in relation to the social semiotic view of meaning-making in the EFL context outlined above, focusing on how engaging in these types of practices might influence EFL learners’ meaning-making processes from a theoretical viewpoint (see also Brown & Alford, 2023).

The first dimension, disrupting the commonplace, centres around the unsettling of meaning-making processes and challenging what is taken for granted as ‘normal’. This can be done by engaging in dialogue on questions such as ‘How does this image position us to see the world?’ (Luke & Freebody, 1997), thus encouraging learners to interrogate the choices which went into making the text and their possible effects on them as readers. Such systematic evaluation of how texts are constructed can facilitate an increased awareness of meaning-making resources as producing meaning.

The second dimension, interrogating multiple viewpoints, entails reflecting on the image through multiple perspectives, asking questions such as ‘Whose perspectives are included/not included in this image?’ (Lewison et al., 2015). Through this, learners explore the text from multiple social and cultural perspectives, including interrogating other relevant historical, social or subjective contexts; that is, how specific – real or imagined – people might view the image depending on their context and their understanding of meaning-making resources. As such, an increased understanding of the social and cultural situatedness of texts and meaning-making processes is facilitated.

Working with the third dimension, focusing on the socio-political, entails uncovering the potential interests at play in the image – the effects the image can have in various contexts – and examining how these correlate with one’s personal interests. Such discussions can be prompted by asking, ‘Who benefits from this way of representing the world?’ and ‘Who is disadvantaged?’ (Janks, 2014). Thus, learners are encouraged to view the selection of meaning-making resources as ideological rather than neutral, in the sense that these choices are made with the aim of enforcing certain perspectives (Kearney, 2016).

Finally, the last dimension, , involves using the understanding and experience gained through working within the other three dimensions to inform subsequent actions. This can include suggesting and implementing changes and improvements or creating new texts which challenge these positions, and implies a purposeful employment of meaning-making resources with an awareness of the potential meanings in various cultural contexts.

Thus, through introducing CVL to the EFL classroom, there is an opportunity for learners to develop their understandings of meaning-making resources and processes both in their own and others’ contexts, indicative of intercultural learning. By using the visual mode as a starting point, the learners can engage with and increase their awareness of meaning-making processes through a mode which is central in their lives and which has proved to form a powerful basis for critical discussions (Brown, 2022; Heggernes, 2019).

Previous research on critical literacy and intercultural learning in language-learning contexts

Research on critical literacy in language-learning contexts has tended to focus on outcomes related to language learning and/or critical engagement (Bacon, 2017) rather than intercultural learning. Only a handful of studies have investigated the use of critical literacy with visual and/or multimodal media. However, while few in number and using generally small samples, these studies demonstrate the potential of critical literacy practices as an approach to engaging with cultural stereotypes (Huh & Suh, 2018), developing multiple perspectives on an issue (Kearney, 2012) and gaining self-awareness (Yol & Yoon, 2020).

Similar findings have also been identified in the doctoral research project that the current study builds on, wherein EFL learners in Norway were found to be less inclined to stereotype based on visual cues and also displayed an increased awareness of the process of stereotyping following a critical visual literacy intervention (Brown, 2019). Furthermore, the process of engaging in critical dialogue surrounding images was found to be instrumental in enabling the learners to develop multiple perspectives, with the learners increasing their agency in this co-construction process following the intervention (Brown, 2022). Agency, understood here as the capacity to engage critically with images and make informed choices based on this engagement, was also identified in the learners’ use of knowledge and analytical tools gained through instruction to identify underlying ideologies in an advertisement, problematise these and challenge them through creating alternative texts (Brown, 2021b).

These studies point to the potential of facilitating intercultural learning through CVL practices in the EFL classroom, but there is still a lack of research that highlights the ‘micro-processes’ of critical approaches (Vossoughi & Gutiérrez, 2016, p. 143). Although examples exist in first language settings (e.g., Cho, 2015; Mantei & Kervin, 2016; Papen, 2020), such research is almost absent from language-learning contexts, with some notable exceptions (e.g., Lau, 2013). This is problematic, given that previous research has found that a lack of understanding of critical literacy is one of the main challenges teachers identify when they want to implement it in their classrooms (Cho, 2015). The current study aims to contribute to filling this research gap by giving voice to learners and teachers, presenting their views on the opportunities and challenges afforded by CVL practices in the context of Norwegian upper secondary EFL classrooms.

Methodology

The current study draws on previously unreported data from a doctoral research project conducted in an upper secondary school located in a medium-sized city on the west coast of Norway in 2017 (Brown, 2021a). The aim of this qualitative case study (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) was to explore the meaning-making processes upper secondary EFL learners engage in when reading images from the perspective of intercultural learning before and after being introduced to CVL practices. To investigate this, 83 learners from three first-year EFL classes and their three teachers participated in a 16-week intervention in which CVL tasks were introduced as an integrated part of their English language classes. Due to the demands on the participating teachers’ time, effort and willingness to collaborate, the three teachers and their classes were selected through convenience sampling. While such sampling does compromise the choice of participants (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013), the final group of participants consisted of three intact classes of upper secondary school learners with a relatively even gender balance, in which roughly a quarter of the learners reported to have one or both parents born in a country other than Norway. Moreover, learners from the first year of general studies, the only year of upper secondary school where English is a compulsory subject, were purposely selected in preference to second- and third-year classes where students study English by choice, which would potentially reduce diversity and make the findings less transferable.

Due to the three teachers’ inexperience with CVL, training was provided at initial meetings, where we discussed what CVL entails and how it could fit in with their general approach to teaching. In addition, weekly meetings were held during the intervention where we would discuss potential tasks to implement in the following week(s). In total, twelve tasks were implemented, ranging from shorter 10-minute tasks, for example, guessing what a photograph of Native Americans might look like and reflecting on the sources of these assumptions, to full 80-minute lessons, for example, critiquing and re-designing a multimodal advertisement (see Brown, 2019, pp. 138–40, or Brown, 2021a for a full overview of the tasks in the intervention). When combined, these added up to 9 hours, which amounts to roughly twenty per cent of the total teaching time for the English subject during the period.

During the intervention, I was an active participant, meaning that I had ‘a central place in the site or setting, by functioning within it as well as observing it’ (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013, p. 396), and I was also instrumental in the implementation of a majority of the tasks, which contributed towards securing intervention fidelity. Specifically, in cases where tasks included an introductory lecture, I would hold the lecture in an auditorium with all three classes attending simultaneously. I would then introduce the task, before the learners returned to their respective classrooms to complete it. Otherwise, the tasks were introduced by the three teachers in the respective classes, for which they were provided materials and instructions for implementation as support. As an active participant, I shared my time between the three classes during task completion, which contributed further to securing intervention fidelity.

Data was collected from student artefacts produced in relation to the CVL tasks, such as written responses to questions or their re-designed multimodal advertisements, as well as from questionnaires and focus group interviews conducted before and after the intervention. During the intervention, I took detailed field notes both during and after each lesson, as well as during meetings with the three participating teachers.

The current article draws on a combination of these researcher field notes and the learners’ responses to one questionnaire item aiming to elicit their reflections on their learning throughout the intervention. This item was included in the , where the learners were provided with a list of the tasks they had participated in during the intervention, , ‘Write a bit about how you have experienced working with images in this way. Please feel free to include both positive and negative experiences.’ In total, 79 of the 83 learners consented to participate in the questionnaire. Additionally, four learners were absent and two did not respond to the item in the post-intervention questionnaire. Consequently, 73 responses to the item, ranging from short one-sentence responses to full paragraphs, were collected and all of these were included in the data set. The field notes include my own observations as a teacher-researcher in each lesson, as well as comments made by the three teachers throughout their participation in the study during lessons and weekly meetings. By combining learners’ and teachers’ voices, I hope to provide a fuller view of the challenges and opportunities that occur when CVL is introduced in the EFL classroom.

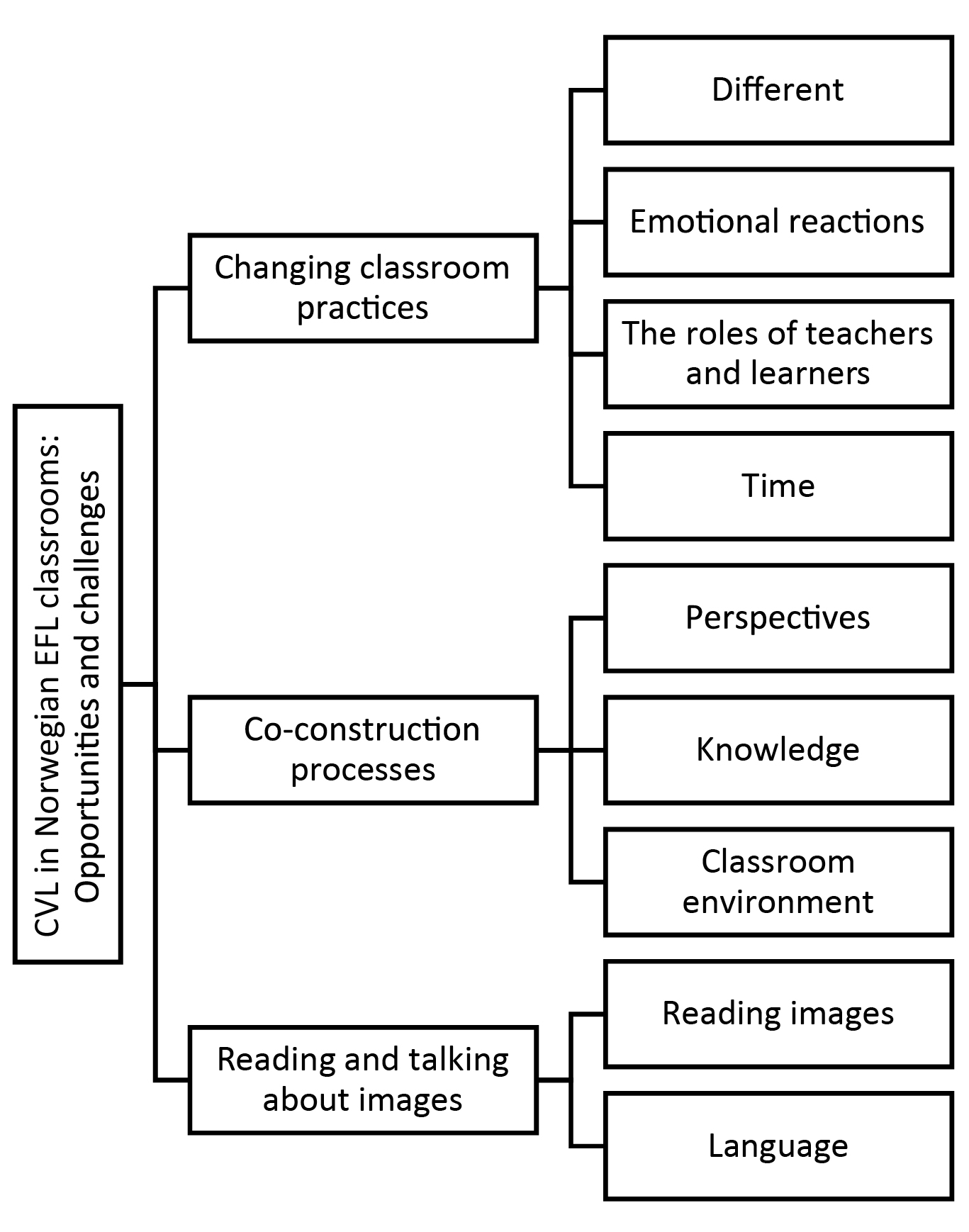

The data set was analysed qualitatively using elements of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), with the aim of identifying the major themes as seen through the lens of opportunities and challenges. Careful reading of the data set and coding according to the content was carried out before collating codes into potential themes. The themes and codes were then revisited and revised for internal consistency and representativeness before the final thematic map was developed (Figure 1). For example, the initial codes ‘Critiqued for opinions’ and ‘Lack of participation’ were first collated into a provisional theme ‘Classroom environment’. However, due to the relative low number of occurrences, the provisional theme was later incorporated as a collated code in the larger theme ‘Co-construction processes’. The quality of the coding process was increased through ensuring that all data items were given equal attention and that the themes were generated through a thorough, inclusive and comprehensive coding process, thereby avoiding what Braun and Clarke (2006) call ‘an anecdotal approach’ (p. 96). For brevity and reader-friendliness, the initial codes that formed the collated codes are not systematically described and elaborated on below unless they are relevant for understanding the findings within the collated code.

Findings and discussions

Three main themes were identified as a result of the thematic analysis, namely ‘Changing classroom practices’, ‘Co-construction processes’ and ‘Reading and talking about images.’ In the following, the opportunities and challenges related to each theme will be discussed sequentially, also drawing on previous research and theoretical work within the wider field of critical literacy to suggest pedagogical implications.

Changing classroom practices

The theme ‘Changing classroom practices’ concerns challenges and opportunities related to the ways in which the introduction of CVL changed the classroom practices in the three classrooms, and, by extension, the roles of the learners and teachers.

A prominent code identified in the learner responses (LR) included in this theme was ‘Different’, which consists of statements that explicitly mentioned that the CVL project incorporated a different way of working. The learner responses within this code, which amounted to 15 in total, highlighted that the CVL project had them working ‘in more varied ways’ (Participant 39 (P39), LR), with topics that focused ‘a bit more on the people’ (P31, LR), and in a more interactive way, arguing that it is better than ‘the teacher just standing and talking all the time, because I think we learn more by being active ourselves’ (P26, LR). Most of the comments within this code included a positive assessment of the change, while two remained neutral. The learners’ positive assessment of the project was also reflected in the code ‘Emotional reactions’ which consists of two sub-codes, ‘Boring’ and ‘Interesting and fun,’ with four and 35 coded responses respectively. This change in classroom practices thus appeared to create an opportunity for increased learner engagement, which is an important factor in successful language learning (Svalberg, 2018), although notably four learners disagreed, stating that it was ‘a bit boring occasionally’ (P65, LR) or that they ‘found most of the “exercises” to be boring’ (P69, LR), and many learners did not comment on their emotional reactions to the project.

While the changes in the ways of working within the classroom were generally mentioned in positive terms in the students’ responses, some challenges were identified within the code ‘The roles of learners and teachers.’ For example, the field notes (FN) relate the reflections of one of the teachers who observed that many of the students struggled with the lack of defined answers in one of the tasks. The task in question was included early in the intervention and required the learners to write topic sentences about different photographs based on what they could see. The teacher commented that many students struggled with the task ‘as they were too concerned about getting facts rather than using their imagination’ (FN). This might reflect an expectation on the part of the learners that the teacher would be the ‘keeper of knowledge’ which could be transmitted to the learners, whose role it would be to recall and display assigned information (Nystrand et al., 2003). Such a view of education is in line with what Freire (1993) called the ‘Banking model of education.’ This model of education is not conducive to the exploratory approach implied by CVL practices, where the aim is to produce complexity and increase the learners’ understanding of and control over meaning-making processes.

In line with this, during the intervention, the teachers and I attempted to follow Freire’s (1993) ‘Problem-posing model of education’, in which teachers and learners solve problems together by co-constructing knowledge through critical dialogue. Rather than asking questions which aim to elicit pre-defined answers, we attempted to ask open questions and allow the dialogue to develop from the learners’ contributions. However, as also documented in Brown (2022), these attempts were not always successful. Critical dialogue requires the teacher to be particularly aware of their position of authority in the classroom, both when it comes to facilitating dialogue and when deciding which concepts to bring in and how. For example, one learner reflected that ‘The problem is that when we know we are working on stereotypes and racism I think we easily try to find examples of this in the images’ (P81, LR). This is both a challenge and an opportunity, as critical engagement with how concepts such as stereotypes and racism influence meaning-making processes are central to intercultural learning. Simultaneously, how and when these concepts are introduced are likely to influence the learners’ meaning-making processes, which requires continuous reflexivity on the part of the teacher. For example, following a lesson where the learners critiqued a montage of Indigenous people, I voiced a concern about my focus on visual stereotypes in relation to Indigenous peoples and wrote that ‘I wish I had pointed out more clearly that it is not a problem to show [Indigenous peoples’] traditional cultural clothing and artefacts, but that this is only one part of a big and complex picture’ (FN). The process of writing and reflecting on notes from lessons could be seen as part of a continuous reflexive practice which should encompass the planning and implementation of critical teaching (Lau, 2015).

A related issue identified in the data under the code ‘Time’ was that engaging in critical dialogue can be quite time consuming. In particular, given the close integration of CVL tasks in the English lessons during the intervention, the researcher field notes highlight the challenge of balancing the need to stick within agreed-upon timelines and the wish to encourage open, critical dialogue. Similar concerns were raised by Cho (2015), who reflects on their own role as teacher: ‘I struggled with issues of control versus freedom in determining how much of the class needed to be pre-planned to ensure efficiency and how much needed to be responsive to the emergent dialogue among students’ (p. 74). In contrast, time was only mentioned in two learner responses and although both were negative to the amount of time spent, one of them reflected that it ‘is not just negative, because spending time on it means that we get a more in-depth understanding of the issues’ (P35, LR). This comment is timely given the focus on in-depth exploration and creativity in the revised Norwegian curriculum.

Co-construction processes

The second theme identified in the data material encompasses learners’ and teachers’ reflections on opportunities and challenges related to the co-construction processes inherent in critical dialogue from three angles, namely perspectives, knowledge and classroom environment.

The most prominent code within this theme was that of perspectives, which was identified in 18 of the learner responses. Here, the learners highlighted the opportunities CVL practices afforded in terms of being able to voice and/or expand or change one’s own perspectives, arguing, for example, that ‘I think it is fun to work with images and be allowed to understand things in our own way and have our own opinions about what we think’ (P15, learner reflection). From a CVL perspective, learners are not seen as passive receivers of knowledge but rather as people who come to the classroom with diverse and rich experiences and knowledge which can be brought into the joint co-construction process. Indeed, through the practice of ‘Disrupting the commonplace’ (Lewison et al., 2002), the learners’ own understandings should form the starting point for dialogue. By asking open questions and being genuinely interested in what the learners bring to the dialogue, there is thus an opportunity for teachers to increase the learners’ engagement with the meaning-making process.

Such engagement can work as a starting point to exploring how ‘their own way’ and ‘own opinions’ are shaped by the social and cultural contexts they participate in, thus encouraging intercultural learning. Thirteen of the learners voiced their appreciation of being able to challenge and/or expand their own perspectives, arguing, for example, that ‘through conversations I got a lot of input from my peers and teachers which gave me a new perspective on how we can look at images’ (P38, LR). Since each individual in the classroom will have their own unique background, even relatively ‘homogenous’ classrooms are likely to be diverse in many ways. Through engaging in critical dialogue, the learners are thus given the opportunity to co-construct more complex knowledge about the issues, drawing on their multiple and diverse knowledge and experiences (Brown, 2022). This is in line with the aims of the English subject to ‘open up for new ways to interpret the world’ (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019, p. 3).

One challenge identified in the field notes within the code ‘Knowledge’ was the learners’ lack of knowledge about the issues explored. For example, the teachers in my study raised the concern that ‘some of the pupils might not know enough about Indigenous people from before’ (FN) to be able to complete one of the tasks. It is important to note that the spatial and/or temporal distance of the issues explored in the EFL classroom (Kearney, 2012) requires learners to have knowledge about the world. As pointed out by Mantei and Kervin (2016), it is challenging to focus on the socio-political issues related to images when the learners’ knowledge about such issues might be limited due to their age and life experience. Moreover, engagement in CVL practices should come with a responsibility on the part of both teachers and learners to seek knowledge, otherwise there is a risk that learners just perpetuate their previous beliefs and understandings rather than challenging and expanding them. As one learner reflected, ‘I thought it was great to work in a way where I could think for myself and challenge the way we see other people and cultures’ (P40, LR, my emphasis). This is in line with the core curriculum, which states that education must ‘seek a balance between respect for established knowledge and the explorative and creative thinking required to develop new knowledge’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017, p. 7). The learner responses identified within this code were generally positive in their assessment and, although few in number, pointed to the importance of ‘reflecting on current topics’ (P43, LR) and showing an interest in expanding their knowledge base. As such, although the role of the teacher as ‘keepers of knowledge’ is not in alignment with CVL practices, teachers can work as facilitators by modelling curiosity and providing materials for learners to expand on their knowledge. This is particularly important from the perspective of intercultural learning, where an understanding of different social and cultural contexts is central. As such, CVL practices should not be treated as isolated events, but rather be incorporated into the teaching in such a way that the learners can support their critique with historical, contextual information and knowledge (Brown & Alford, 2023).

A final challenge related to this theme was identified within the code ‘Classroom environment.’ This code was identified mainly in the field notes, where concerns about a lack of participation in full-class discussions were raised, but also in the following learner response: ‘The positive with these images is that we get to see how other people view things […]. The negative is that people get criticized for stating their opinions’ (P58, LR). When teachers invite learners to bring in their own experiences, opinions and emotions into the classroom dialogue, they are also asking them to expose themselves and to become vulnerable to the comments and judgements of their peers and teachers. The experience outlined in the learner quote above is not constructive for creating a classroom environment for critical dialogue, which requires mutual trust between the teachers and the learners, and among the learners. Abednia (2015) suggests that teachers should make explicit the aims and rules of this type of dialogue, such as openness, humility and respect for difference of opinion. Teachers can also facilitate the dialogic process by providing specific feedback and advice on how to be a good listener, for example, by offering eye contact to the speaker and paying attention to their peers’ responses (Abednia, 2015). Creating an environment where learners feel free to share their perspectives is crucial in order to facilitate the co-construction processes described above, and also to provide learners and teachers with the opportunity to challenge their own assumptions, an important part of intercultural learning, as opposed to just engaging in critique from a safe distance (Lau, 2013).

Reading and talking about images

So far, the themes have dealt mostly with opportunities and challenges which could relate to critical literacy practices more generally. However, there are also some more specific opportunities and challenges identified in the data set that arise from the unique ways in which images communicate, found within the code ‘Reading images,’ and how the pupils were expected to communicate about the images, coded within ‘Language.’ The code ‘Reading images’ was identified in 16 learner responses. Many of these mentioned the images in positive terms. For example, one learner reflected that they liked images because they ‘illustrate things differently than just words,’ (P83, LR) and another stated that they felt they learned more during the project because images ‘help me remember things we have gone through in the lesson’ (P47, LR). Six of the learners stated that they found it challenging to analyse and interpret images, pointing out that it was ‘difficult at times’ (P62, LR) and ‘not always so easy to interpret images’ (P29, LR). The fact that images communicate differently to words thus appeared to pose a challenge to some of the learners. As one learner reflected, ‘It is difficult to express oneself with the right words, especially orally. The pictures create a situation where you often need to explain it orally, which I find difficult (and maybe good practice)’ (P83, LR).

As Skulstad (2020) points out, people are not accustomed to arguing verbally against visual messages, which contributes to their persuasiveness. In order to ‘talk back’ to the messages in images practice is needed, as the learner above alluded to in their reflection, and there might also be a need to ‘demonstrate a specific way of examining and talking about the pictures’ (Papen, 2020, p. 8). Such practice and modelling, which can be provided through CVL, is essential given the increasingly complex and visually dominated textual environment learners navigate today.

The code ‘Language’ reflects both the learners’ and teachers’ concerns regarding the linguistic challenges posed by engaging in CVL practices related to both the use of English in oral discussions more generally and the specific terminology employed in the CVL intervention. In relation to the first of these, the teachers in the study shared a common understanding that the learners’ reluctance to participate in full-class discussion stemmed from worrying ‘about speaking English in front of the whole class’ (FN). This view can be corroborated by observations that learners were very active during pair and smaller group discussions, when the number of participants was lower. Although the expected level of English proficiency for secondary learners in Norway is quite high (Hasselgreen, 2005), particularly in relation to oral skills, learners come to the classroom with a variety of proficiency levels. For some learners, it might prove difficult to participate in unscripted critical dialogues, which coincides with French and Norwegian EFL teachers’ reflection regarding the introduction of critical literacy as part of a professional development project: ‘to work in-depth with critical literacy required a great degree of both language and visual scaffolding’ (Normand et al., 2022, p. 285). Indeed, one learner in my study suggested that ‘It would have been easier and more fun if it had not been in English, but in Norwegian’ (P5, LR). Although only voiced by one learner in the current study, the language demands of CVL practices need to be considered in lower proficiency classrooms and teachers might consider opportunities for cross-curricular work where the analytical tools are introduced in the learners’ first language. This might also address concerns raised by the teachers and two learners in my study, namely that ‘some of the tasks are a bit difficult to understand’ (P26, LR), which the teachers speculated was due to ‘some of the vocabulary used in the questions,’ such as ‘portraying,’ ‘positioning’ and ‘detachment’ (FN). While the introduction of a metalanguage has been found to facilitate critical explorations of images (Brown, 2021b; Callow, 2003), an initial introduction of these terms in the learners’ first language might be necessary scaffolding in some cases.

It is important to point out that most of the learners in the study did not mention language requirements, a finding which supports previous research that has challenged the notion that language learners are not proficient enough to engage in critical literacy practices (Luk & Hui, 2017; Yol & Yoon, 2020). Moreover, using images as prompts for these critical dialogues also means that the learners do not have to overcome the linguistic challenge of reading, for example, a whole novel. As such, the demands of reading and creating meaning from the text is something that most of the learners will have an equal opportunity to participate in, regardless of their English proficiency level. Such texts choices are also supported by the broad definition of texts in the current English curriculum in Norway (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019).

Concluding remarks

The current article has presented learners’ and teachers’ perspectives on the opportunities and challenges that can arise when engaging in CVL practices in the context of Norwegian EFL classrooms. Building on a larger research project which focused on the benefits of such practices in relation to intercultural learning, the current study expands on this by including learners’ and teachers’ voices.

The findings suggest that introducing CVL in the EFL classroom can be challenging for teachers and it requires a high level of flexibility and reflexivity in their role as facilitators. Moreover, the introduction of such practices in Norwegian EFL classroom relies heavily on the individual teacher’s knowledge of, experience with and willingness to include CVL. For the learners, it can be challenging to adapt to new literacy practices or ‘ways of being and doing’ (Vasquez et al., 2019, p. 308). It is important to see engagement in such practices as a gradual process of socialisation into the practices of critical reading, dialogue and reflection (McConachy, 2018), and to provide sufficient scaffolding in this process. Given that there is no long tradition of critical (visual) literacy practices in Norwegian EFL classrooms, it is questionable whether teachers are equipped to provide this scaffolding and there might be a need for professional development and teacher education to support teachers in this work.

Despite these challenges, however, this study indicates that a number of opportunities can arise from engaging in CVL practices with EFL learners in terms of: (a) preparing them not only to navigate the complex and diverse textual landscapes they encounter in their current and future lives, but to actively participate in these by making informed decisions and actions (Brown, 2021b; 2022); and (b) increasing their awareness of meaning-making processes as socially and culturally situated (Brown, 2019, 2022), thus addressing some of the overarching aims related to intercultural learning in the English curriculum. I would like to end the article with a learner response which reflects the potential for CVL to encourage a deeper understanding of intercultural meaning-making processes: ‘What I have learned through these lessons is that there are usually people who look at things differently. Just because you are right doesn’t mean that the others are wrong’ (P34, LR).

Litteraturhenvisninger

Abednia, A. (2015). Practicing critical literacy in second language reading. The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 6(2), 77–94.

Bacon, C. K. (2017). Multilanguage, multipurpose: A literature review, synthesis, and framework for critical literacies in English language teaching. Journal of Literacy Research, 49(3), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X17718324

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, C. W. (2019). “I don’t want to be stereotypical, but…”: Norwegian EFL learners’ awareness of and willingness to challenge visual stereotypes. Intercultural Communication Education, 2(3), 120–141.

Brown, C. W. (2021a). Critical visual literacy and intercultural learning in English foreign language classrooms: An exploratory case study [Doctoral dissertation, University of Stavanger]. Brage. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2789633

Brown, C. W. (2021b). Taking action through redesign: Norwegian EFL learners engaging in critical visual literacy practices. Journal of Visual Literacy, 41(2), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144X.2021.1994732

Brown, C. W. (2022). Developing multiple perspectives with EFL learners through facilitated dialogue about images. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 19(3), 214–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2022.2030228

Brown, C. W., & Alford, J. (2023). Critical literacy in the language classroom: Possibilities for intercultural learning through symbolic competence. Intercultural Communication Education, 6(2), 36–52.

Callow, J. (2003). Talking about visual texts with students. Reading Online, 6(8), 1–16.

Cho, H. (2015). ‘I love this approach, but find it difficult to jump in with two feet!’ Teachers’ perceived challenges of employing critical literacy. English Language Teaching, 8(6), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n6p69

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

Felten, P. (2008). Visual literacy. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 40(6), 60–64.

Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum. (Original work published 1970)

Hasselgreen, A. (2005). The new læreplan proposal for English – Reading between the lines. Språk og språkundervisning, 2(5), 7–10.

Heggernes, S. L. (2019). Opening a dialogic space: Intercultural learning through picturebooks. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 7(2), 37–60.

Huh, S., & Suh, Y.-M. (2018). Preparing elementary readers to be critical intercultural citizens through literacy education. Language Teaching Research, 22(5), 532–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817718575

Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power. Routledge.

Janks, H. (2014). The importance of critical literacy. In J. Z. Pandya & J. Ávila (Eds.), Moving critical literacies forward: A new look at praxis across contexts (pp. 32–44). Routledge.

Janks, H., Dixon, K., Ferreia, A., Granville, S., & Newfield, D. (2014). Doing critical literacy: Texts and activities for students and teachers. Routledge.

Kearney, E. (2012). Perspective-taking and meaning-making through engagement with cultural narratives: Bringing history to life in a foreign language classroom. L2 Journal, 4(1), 58–82. https://doi.org/10.5070/L24110010

Kearney, E. (2016). Intercultural learning in modern language education: Expanding meaning-making potentials. Multilingual Matters.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203970034

Lau, S. M. C. (2013). A study of critical literacy work with beginning English language learners: An integrated approach. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 10(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2013.753841

Lau, S. M. C. (2015). Relationality and emotionality: Toward a reflexive ethic in critical teaching. Critical Literacy: Theories & Practices, 9(2), 85–102.

Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79(5), 382–392.

Lewison, M., Leland, C., & Harste, J. C. (2015). Creating critical classrooms: Reading and writing with an edge (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Luk, J., & Hui, D. (2017). Examining multiple readings of popular culture by ESL students in Hong Kong. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 30(2), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1241258

Luke, A. (2014). Defining critical literacy. In J. Z. Pandya & J. Ávila (Eds.), Moving critical literacies forward: A new look at praxis across contexts (pp. 19–31). Routledge.

Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1997). Shaping the social practices of reading. In A. Luke & P. Freebody (Eds.), Constructing critical literacies: Teaching and learning textual practice (Vol. 6, pp. 185–225). Allen & Unwin.

Mantei, J., & Kervin, L. K. (2016). Re-examining “redesign” in critical literacy lessons with grade 6 students. English Linguistic Research, 5(3), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.5430/elr.v5n3p83

McConachy, T. (2018). Critically engaging with cultural representations in foreign language textbooks. Intercultural Education, 29(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2017.1404783

Medietilsynet. (2022). Barn og medier 2022: Barn og unges bruk av sosiale medier [Children and media 2022: Children and youth’s use of social media]. https://www.medietilsynet.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/barn-og-medier-undersokelser/2022/Barn_og_unges_bruk_av_sosiale_medier.pdf

Ministry of Education and Research. (2019). Curriculum in English. https://www.udir.no/lk20/eng01-04?lang=eng

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review 66(1), 60–92.

Newfield, D. (2011). From visual literacy to critical visual literacy: An analysis of educational materials. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 10(1), 81–94.

Normand, S., Dessingué, A., & Wagner, D.-A. (2022). Critical literacies praxis in Norway and France. In J. Z. Pandya, R. A. Mora, J. H. Alford, N. A. Golden & R. S. de Roock (Eds.), The handbook of critical literacies (pp. 281–288). Routledge.

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2017). Core curriculum – values and principles for primary and secondary education. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/om-overordnet-del/?lang=eng

Nystrand, M., Wu, L. L., Gamoran, A., Zeiser, S., & Long, D. A. (2003). Questions in time: Investigating the structure and dynamics of unfolding classroom discourse. Discourse Processes 35(2), 135–198. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326950DP3502_3

Papen, U. (2020). Using picture books to develop critical visual literacy in primary schools: Challenges of a dialogic approach. Literacy, 54(1), 3–10.

Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2013). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Routledge.

Sherwin, R. K. (2008). Visual literacy in action: Law in the age of images. In J. Elkins (Ed.), Visual literacy (pp. 179–194). Routledge.

Skulstad, A. S. (2020). Multimodality. In A.-B. Fenner & A. S. Skulstad (Eds.), Teaching English in the 21st century: Central issues in English didactics (2nd ed., pp. 261–283). Fagbokforlaget.

Svalberg, A. M.-L. (2018). Researching language engagement: Current trends and future directions. Language Awareness, 27 (1–2), 21–39.

Undrum, L. V. M. (2022). Kritisk tilnærming til tekster i sosiale medier: En studie av influenseres tekster på Instagram og unges utfordringer i møte med dem [A critical approach to social media texts: A study of influencers’ texts on Instagram and adolescents’ challenges when encountering them]. Acta Didactica Norden, 16(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.8990

Vasquez, V. M., Janks, H., & Comber, B. (2019). Critical literacy as a way of being and doing. Language Arts, 96(5), 300–311.

Veum, A., Kvåle, G., Løvland, A., & Skovholt, K. (2022). Kritisk tekstkompetanse i norskfaget: Korleis elevar på 8. trinn les og vurderer multimodale kommersielle tekstar [Critical Literacy in the subject Norwegian: How students (13–14 years) read and evaluate multimodal commercial texts]. Acta Didactica Norden, 16(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.8992

Veum, A., Layne, H., Kumpulainen, K., & Vivitsou, M. (2021). Critical literacy in the Nordic education context. In J. Z. Pandya, R. A. Mora, J. H. Alford, N. A. Golden, & R. S. de Roock (Eds.), The handbook of critical literacies (pp. 273–280). Routledge.

Vossoughi, S., & Gutiérrez, K. D. (2016). Critical pedagogy and sociocultural theory. In I. Esmone & A. N. Booker (Eds.), Power and privilege in the learning sciences (pp. 157–179). Routledge.

Yol, Ö., & Yoon, B. (2020). Engaging English language learners with critical global literacies during the pull-out: Instructional framework. TESOL Journal, 11(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.470