Hvorfor digitaliserer norske utdanningsmyndigheter utdanning? En analyse av politiske argumenter i politikkdokumenter

Over hele verden er interessenter innen utdanning opptatt av å tilby skoler tilgang til digital teknologi. Norge er intet unntak. Siden 2006 har digitale ferdigheter blitt ansett som grunnleggende ferdigheter som bør gjennomsyre alle skolefag, på tvers av klassetrinn.

Vestlige utdanningsmyndigheter har i de siste tiårene massivt presset på for å iverksette digitale ferdigheter i utanningen. Argumentene for å iverksette digitale ferdigheter som del av pensum er ofte uklare. Denne artikkelen presenterer en kritisk diskursanalyse av politiske argumenter som angår ‘digitale ferdigheter’ i norsk utdanningspolitikk for vidregående utdanning. Studien er inspirert av Fairclough, da mitt hovedanliggende var å undersøke meningsinnholdet i de ulike tekstene som danner utgangspunkt for denne studiens datamateriale. Utvalgte utdrag fra politikkdokumentene ble analysert for å identifisere hvilke hovedpolitiske argumenter og retorikk relatert til digitale ferdigheter som er tydelige i disse tekstene. Et utvalg av 20 norske stortingsmeldinger, pensum og NOU-er fra 1990-årene til implementeringen av Kunnskapsløftet (LK20) i 2020 ble analysert. Artikkelens hovedfunn viser at siden tidlig på 1990-tallet har norske utdanningsmyndigheter hatt stor teknologioptimisme. Studien viser også at den politiske diskursen om digitale ferdigheter i stortingsmeldingene er dominert av kapitalistiske og nyliberale perspektiver. Disse perspektivene er særlig tydelige i stortingsmeldingene fra 2013 til introduksjonen av kjerneelementene i LK20 i 2020.

Why Are Norwegian Education Authorities Digitising Education? An Analysis of Political Arguments in Policy Documents

Educational stakeholders worldwide are concerned with providing access to digital technology in schools. Norway is no exception. Since 2006, digital skills have been considered basic skills that should permeate all school subjects, across grades.

Western education authorities have, in recent decades, massively pushed to implement ‘digital skillsʼ in education. The arguments for implementing digital skills as part of curricula are often vague. This article presents a critical discourse analysis of the political arguments concerning ‘digital skillsʼ in Norwegian upper-secondary-school education policy. This study is ‘Fairclough inspiredʼ, as my main concern was studying the meaning content of the various texts that make up this studyʼs data material. Selected excerpts from education policy documents were analysed to identify which main political arguments and rhetoric related to digital skills are evident in these texts. A selection of 20 Norwegian white papers, curricula and Norwegian Official Reports was analysed from the 1990s to the introduction of the new national curriculum, The New Knowledge Promotion (LK20), in 2020. This articleʼs key findings show that, since the early 1990s, Norwegian education authorities have harboured substantial technological optimism. This study also shows that white papersʼ digital skills–related policy discourses regarding Norwegian upper secondary schools have been dominated by capitalist and neo-liberal perspectives. These perspectives are particularly evident in white papers from 2013 to when the school reformʼs core elements were introduced in LK20 in 2020.

Introduction

Educational stakeholders worldwide are concerned with providing access to digital technology in schools. Norway is no exception. Since 2006, digital skills have been considered basic skills that should permeate all school subjects, across grades (Erstad, 2010, pp. 17–18). In August 2020, The New Knowledge Promotion (LK20) was implemented, and it is the most ambitious curriculum ever to have launched in Norwegian schools regarding digital skills. Programming and coding are now compulsory for upper-secondary-school pupils in the core subjects of mathematics and natural science. Also, fifth-grade students will now learn programming and coding, while the fourth-grade mathematics curriculum states that students should ‘create algorithms and express these using variables and loopsʼ (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2020). The Norwegian curriculumʼs emphasis of increasingly complex training in digital skills is evident through the 20 official documents that I analysed in this study. My main research question is: Why are the Norwegian education authorities digitising the Norwegian education system? To answer this question, I conducted Fairclough-inspired critical discourse analysis (CDA) of excerpts from education policy documents, 20 Norwegian white papers, curricula and Norwegian Official Reports (NOUs) regarding the main political arguments related to the education systemʼs digitalisation. These documents cover the period from the early 1990s to the implementation of The New Knowledge Promotion in 2020. The following question guided my analyses of educational policy documents: Which main political discourses related to digital skills are evident in Norwegian education policy from this period?

Methods: Faircloughʼs Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)

In this study, which draws on work from my Ph.D. thesis (Klausen, 2020), I aimed to identify different political discourses related to digital skills and digital competency in 20 Norwegian white papers, curricula and NOUs and to discuss my findings using concepts from Faircloughʼs CDA theory. Fairclough (2003b, p. 21) defined discourse as follows: ‘Different positions in the political field give rise to different representations, different visions … looked at from a language perspective, different representations/visions of the world are different “discourses”ʼ. Faircloughʼs CDA is both a theory and a method. CDA provides a toolbox of different concepts that can be used to analyse different forms of text. Skrede (2017) stated that researchers need not use all these concepts. Which concepts researchers choose to use depends on the purpose of their analysis (Skrede, 2017, p. 58). In the current study, therefore, I used Faircloughʼs different concepts eclectically, to clarify which political discourses emerge clearly from my studyʼs empirical data concerning digital skills at Norwegian schools. Fairclough used the same procedure in several of his articles that applied CDA as their theoretical framework, and other authors who use CDA have taken the same approach (cf. Taylor, 2004; Haugsbakk, 2008; Skrede, 2011, 2013). I have mainly used the concepts presented in Table 1. I will explain the different concepts I used to analyse the discourses that arose in the texts I examined.

Table1 Faircloughʼs concepts that are central for this study

|

Theme: |

Central concepts: |

Theme: |

Central concepts: |

|

Discourse and argumentation |

Type of argumentation |

Discourse and social change |

Recontextualization |

|

Discourse and power |

Power in discourse |

Discourse and history |

Past, present, future |

|

Discourse, ‘common senseʼ and ideology |

Political ideology |

Discourse and practice |

Production of texts |

Fairclough, Marxism, Interdisciplinarity and the Three-Dimensional Model

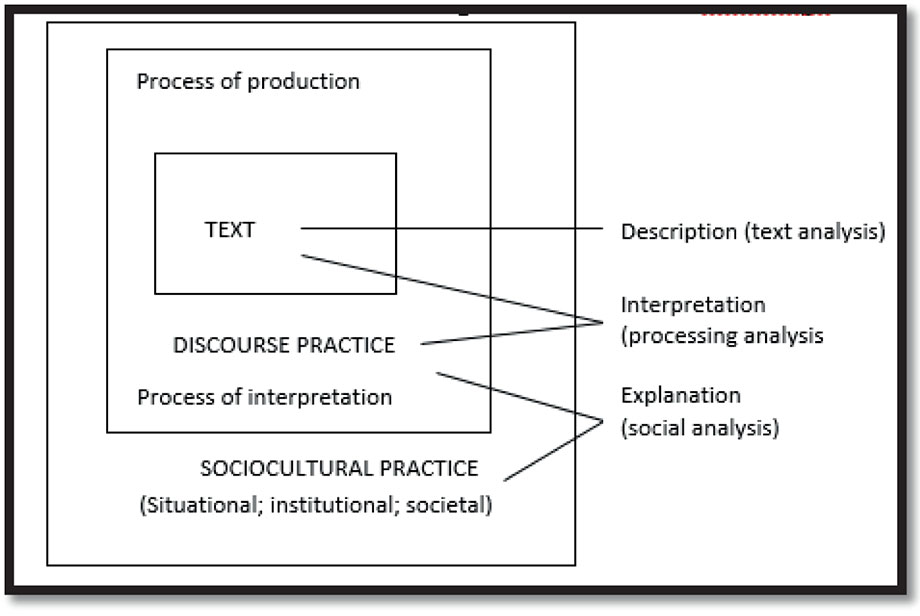

Fairclough (1995) stated that the main argument for using CDA is ‘to make visible through analysis and to criticise, connections between properties of texts and social processes and relations (ideologies, power relations) which are generally not obvious to people who produce and interpret those textsʼ (p. 97). Importantly, Faircloughʼs CDA theory and its attitude toward social change sprung from a Marxist mindset. Fairclough noted that most people today live in capitalist or partially capitalist societies (p. 28). He pointed out that a capitalist social order is characterised by a continuous flow and exchange of economic capital, and that CDA must assess how capitalism characterises power relations and different discourses at institutions and in society as a whole (pp. 29–30). This part of Faircloughʼs CDA theory especially reveals its Marxist character. Fairclough argued that, by using CDA, researchers seek explanations for dialectical relations and, therefore, the effects of different societal elements on one another at the micro-, meso- and macro-levels (pp. 11–12). He designed his three-dimensional model (see Figure 1) as a tool for CDA (Skrede, 2017, pp. 29–34).

According to Fairclough (1995, p. 97), every use of language is a communicative event involving three dimensions: text, discursive practice and social practice. Hence, Fairclough argued that CDA must be conducted on micro-, meso- and macro-levels. The following subsections present the three levels of Faircloughʼs model.

Level 1: Text

Fairclough argued for a broad text concept. In his CDA, ‘textʼ refers to spoken words, written text (documents, newspaper articles, etc.), images and video or combinations of words and images (Fairclough, 1992, p. 73; 2016, p. 4). The current studyʼs data material comprised text in the form of official documents. Fairclough (2015, p. 74) stated that, when a researcher analyses texts according to Level 1 of the three-dimensional model, both ‘language formsʼ and ‘meaningʼ are important. Hence, this study is ‘Fairclough-inspiredʼ, as my main concern was studying the meaning content of the various texts that make up this researchʼs data material. Selected excerpts from education policy documents were analysed to document which political arguments related to digital skills are evident in these texts. Fairclough himself conducted several critical discourse analyses in which he precisely concerned himself most with various textsʼ political arguments and meaning content (cf. Fairclough, 2010, 2000, 1992b, 1995b).

Level 2: Discursive Practice

Fairclough (2016, p. 78) stated that discursive practice involves processes of text production, distribution and consumption, and he described the nature of these processes. Who wrote a text? Who sent the text? Who received the text? How can the recipient perceive the text?

Level 3: Social Practices or Social Structures

The Level 3 concept describes societal macro-conditions (Skrede, 2017, p. 32). According to Fairclough (2003a, pp. 9–10, 218), Level 3 reflects the relationship between discourse, power and ideology. Social practice or social structures can be economic structures, power relations, bureaucratic elements, and so on (Skrede, 2017, p. 32). Fairclough (cf. 2015, p. 49) stated that, to understand changes in society, researchers must draw on various theories from social science, history and other disciplines.

Selection Criteria for White Papers and Official Documents

To select which white papers, curricula and other official documents to analyse in this study, I used the following selection criteria:

- I searched for white papers containing themes or topics of technology and digitalisation published between Curriculum Reform 94 and the LK20 (implemented in 2020). I conducted my search on the federal governmentʼs official website, where all white papers are archived as digital files from 1993 to the present. After conducting this search, I drafted a list of all the white papers that I found relevant for this project.

- I read through references in the relevant professional literature and previous research in the field of digital skills and digitalisation at schools in Norway. I also mapped out which official documents previous research on these themes and topics had referred to.

- I compared the lists from points 1 and 2 above and selected white papers and official documents that the professional literature had repeatedly referenced. Additionally, I supplemented this list of selected documents with documents from the early 1990s which also addressed the digitisation of education (see Tables 2 and 3).

Since white papers, curricula and official reports are very comprehensive, I conducted CDA of the selected documents using what Skrede (2017, p. 161) called ‘examples from the original textʼ or text samples. Skrede (2017) specified the following:

If one is to analyse a political document on several hundred pages, it goes without saying that one cannot go into depth on everything … to handle large amounts of data … select a small number of examples from the parent text that are critically examined. … This makes analyses of larger documents manageable. (pp. 160–162)

For this study, I selected text samples related to the themes of technology, digitalisation at schools, and the use of digital learning tools. While selecting text samples to analyse, I strove to follow Skredeʼs advice: ‘It is important to select quotations that are representative of the main trends in the documentʼ (2017, pp. 160–162). To analyse the data material, I uploaded the documents to NVivo for coding and the identification of different discourses. Tables 2 and 3 present the official documents that constitute the basic material for my analysis. I argue that CDA of the selected text samples can provide knowledge about which political discourses emerged from the material.

Table 2 White Papers

|

White Paper, |

Title: |

Government: |

|

White Paper No. 33 (1991-92) |

Knowledge and Expertise |

Ap/The Labour Party |

|

White Paper No. 24 (1993-94) |

Information Technology in Education |

Ap/The Labour Party |

|

White Paper No. 32 (1998-99) |

Secondary education |

Krf, SV and V: |

|

White Paper No. 16 (2001-02) |

The Quality Reform on New Teacher Training |

Krf, H and V: |

|

White Paper No. 30 (2002-04) |

Culture for Learning |

Krf, H and V: |

|

White Paper No. 16 (2006-07) |

Early Intervention for Lifelong Learning |

Ap, SV and Sp: |

|

White Paper No. 17 (2006-07) |

An Information Society for All |

Ap, SV and Sp: |

|

White Paper No. 13 (2007-08) |

Quality in Education |

Ap, SV and Sp: |

|

White Paper No. 11 (2008-09) |

The Teacher – The Role and the Training |

Ap, SV and Sp: |

|

White Paper No. 44 (2008-09) |

Education strategy |

Ap, SV and Sp: |

|

White Paper No. 27 (2015-16) |

Digital agenda for Norway |

H and FrP: |

|

White Paper No. 28 (2015-16) |

Subject-specialization-understanding – A renewal of the Knowledge Promotion |

H and FrP: |

Table 3 Curricula, Norwegian Offical Reports and other official reports

|

Title of document, public agency, and year: |

Government: |

|

The Curriculum Reform 94: |

Ap/The Labour Party |

|

Core Curriculum & |

Ap/The Labour Party |

|

Digital school every day |

Krf, H and V: |

|

Framework for Basic skills |

Ap, SV and Sp: |

|

Pupilsʼ Learning in the School of the Future – A Knowledge Foundation |

H and FrP: |

|

The School of the Future – Renewal of Subjects and Competences |

H and FrP: |

|

The New Knowledge Promotion |

H and FrP: |

|

Future, renewal and digitalisation |

H and FrP: |

Several political documents deal with the digitisation of Norwegian schools. Twenty political documents were selected in this study. I am aware that I could have expanded the selection of public documents to, for example, 30 or 40 documents, and I could have included several documents from the 1990s until 2020. For example, I could have included the following documents: (1) Program for Digital Competence 2004 – 2008 (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2004), (2) Digital Competence: From 4th Basic Skill to Digital Bildung (ITU/Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2003) and (3) In the First Place – Enhanced Quality in Basic Training for Everyone (Norwegian Official Report, NOU 2003:16). A discourse analysis of an extended range of documents could have presented a more complex picture. However, I have endeavoured to select documents that are considered key texts in the studyʼs subject from 1990 to 2020, and I argue that the critical discourse analysis conducted on the selected documents in this study provides interesting and important knowledge about which political discourses and signals emerged from the selected material.

About Corpus Analysis

In addition to CDA, I also used corpus analysis as a research method. Corpus analysis reveals how often certain central words and concepts (keywords) appear in official documents (Fairclough, 2015, p. 20). Such analysis can provide an important indication of political formulations and rhetoric in texts (Fairclough, 2003a, p. 6). By systematically skimming the white papers and official documents in my material, I noted words and concepts which I found to be central. Corpus analysis was conducted in NVivo. Table 4 illustrates which keywords and synonyms were searched for and counted in this studyʼs corpus analysis. Additionally, I searched for antonyms to the keywords listed.

Table 4 Keywords, Synonyms and Antonyms

|

Keywords: |

Synonyms: |

Antonyms: |

|

Digitalisation/ digitize |

Digital, digital skills, digital competency, digital learning tools, ICT |

Analog/ |

|

Technology |

|

Manually |

|

Knowledge |

Skills, mastery, mastering |

Ignorance |

|

Education |

School, schooling, |

Unskilled |

|

Teacher |

Teachersʼ competency, teachersʼ competencies, teachersʼ ICT-competencies, teachersʼ digital skills |

Pupil/student |

|

Pupil/student |

Student/children and young people |

Teacher |

|

Management |

Control, goal management |

Without leadership |

|

Social change |

Change, reform, social development |

Standstill/ |

|

Internet |

Internet access, WiFi, online |

Lack of internet access |

|

Formation |

General education, general knowledge, |

Uneducated |

|

Working life |

Work, employment |

Unemployment |

|

Business |

|

|

|

Economy |

Profitability, value creation, capital, earnings |

Unprofitable |

|

Future |

Tomorrowʼs society/The society of tomorrow |

Past |

|

Upper secondary school |

Upper secondary education and training |

Primary school |

|

Programme for General Studies |

University-preparatory |

Vocational education programme |

|

Vocational education programme |

Vocational training, vocational competence |

Programme for General Studies |

|

Competition |

Competitiveness, to assert in competition |

To lose in competition |

|

Globalization |

Worldwide, internationalization, internationally, transnationally, supranationally, cyberspace |

Nationalization/ |

|

EU |

|

National, Regional, Norway |

|

OECD |

|

National, Regional, Norway |

|

Objective |

Aim, goal, ambitions |

|

|

Efficiency |

|

Inefficiency |

|

Pedagogy |

Pedagogical use of ICT, professional digital competence |

|

|

Digital learning tools |

|

Textbook |

Coding, Categorisation and Thematisation of Materials and Data in NVivo

I began my coding and categorisation work by becoming acquainted with the text samples in my selection, in order to study the meaning content – arguments and rhetoric used in the various texts that were related to the concept of ‘digital skillsʼ presented in the official documents from the Norwegian education authorities. To code the material in NVivo, I chose the approach that Tjora (2012, pp. 174–179) described as ‘the gradually-deductive-inductive methodʼ. With this method, a researcher develops empirical codes inductively, based on the material or data themselves. While coding, I established 300 quotations and variable codes in NVivo. To reduce all 300 of my studyʼs quotations and variable codes to a more manageable level, I drew physical mind-maps depicting whether my findings were visually clear. Using these mind-maps, I created a matrix that eventually contained 17 main categories, reflecting the clearest arguments for implementing digital skills at Norwegian schools, the need for digital skills at schools and the need to change the digital skillsʼ content at Norwegian upper secondary schools from the early 1990s to the LK20ʼs 2020 implementation. These 17 main categories were merged into six main discourses.

Criticism of discourse analysis

Since the early 1990s, multiple variants of discourse analysis have served as a widespread analysis method in the social sciences and humanities. However, the method has also been criticised, especially in quantitative research environments (Antaki et al., 2008, p. 4). This critique has particularly addressed the fact that the selection of empirical data and interpretation of different discourses can appear very subjective or predefined (2008, pp. 4–5). Criticism of CDA has come from several quarters, and Teun van Dijk (1990) and Wodak and Meyer (2008) have been among the discourse theorists who have taken this criticism seriously. Van Dijk has encouraged researchers who use discourse analysis as a method to work systematically and transparently (Antaki et al., 2008, p. 5).

In this article, I have sought to present this studyʼs methodological approach transparently. To further these efforts, I have created three additional tables (Tables 6, 7 and 8) that show readers more examples of the text excerpts I analysed. Importantly, however, I have mainly analysed policy documents; the studyʼs documents and analyses do not reveal formulated policiesʼ practical applications among teachers in schools.

Analysis and Results

By analysing the political documents included in this study, I identified six main political discourses related to digital skills that are evident in the official documents from 1990 to the implementation of The New Knowledge Promotion in 2020. In the following subsections, I identify the arguments underlying three of these discourses – those which I found the most interesting – according to Faircloughʼs three-dimensional model (cf. Figure 1). Jørgensen and Phillips (2013, p. 82) clarified that the three levels of Faircloughʼs model (cf. Figure 1) constitute different dimensions and must, therefore, be separated analytically.

Level 1 Analysis: Text

In this subsection, this studyʼs data material is analysed at Level 1 of Faircloughʼs three-dimensional model. This analysis identified six main political discourses: (a) Norway will lead the world in the use of ICT in schools; (b) working life and businesses need updated competence; (c) the new pupil; (d) schools and textbooks are outdated; (e) teachers are ‘the plug in the systemʼ; and (f) teachersʼ competence must be improved. This article focuses on the first three of these discursive findings: discourses A, B and C. In addition to CDA, I conducted a corpus analysis of some central keywords and concepts which appeared in the official documents (see Table 4). My corpus analysis revealed usage patterns for keywords and concepts, as well as possible micro-political turns over time. Table 4 shows the keywords, synonyms and antonyms I searched for in my corpus analysis. Table 5 presents the main findings of that analysis. I regularly refer to these findings throughout this sectionʼs Level 1 analysis. The following list is a brief description of the three historical trends in the documents from 1991 until 2020.

A. 1991–2020, ‘Norway will lead the world in the use of ICT in schoolsʼ: A prominent discourse in all the documents included in this study suggests that the education authorities have harboured a strong ambition for Norway to be a world leader in the use of ICT in schools since 1991 (Author, 2020, p. 128).

B. 1992–2020, ‘Working life and businesses need updated competenceʼ: All the documents included in this study convey a clear discourse in which education authorities point out that working life depends on the education system supplying employees with the digital skills that working life demands (Author, 2020, p. 130).

C. 2013–2020, ‘The new pupilʼ: Especially from 2013 onwards, the documents point out a lack of programming skills in the population and a need to facilitate childrenʼs and young peopleʼs ability to not only use but also create digital content and digital services. Therefore, a shift in Norwegian education policy is evident from around 2013; students should now, ideally, become digital innovators for the business world (Author, 2020, p. 138).

Table 5 Findings in the corpus analysis

|

Keywords and concepts in the documents: |

Number of times the keywords and concepts are mentioned in the documents: |

|

Work, employment, working life, business, working life and businessʼ need for updated competence |

2,545 |

|

Digital, digitalisation + technology |

2,171 |

|

ICT |

1,981 |

|

EU + OECD (239 + 426) |

665 |

|

Internet |

530 |

|

Teacher |

402 |

|

Internationalization, internationally, worldwide, globalization |

314 |

|

Pupil/student |

283 |

|

Social change, change, reform, social development, future, tomorrowʼs society/the society of tomorrow |

199 |

|

Digital skills, digital competency |

123 |

|

Formation, general education, general knowledge, |

54 |

|

Teachersʼ digital competency, teachersʼ ICT competencies, teachersʼ digital skills, professional digital competence |

48 |

|

Pedagogical use of ICT |

40 |

|

Internet access/WiFi access |

26 |

|

Textbook |

17 |

|

Digital formation, digital bildung |

13 |

|

Digital learning tools |

0 |

Discourse A: Norway Will Lead the World in the Use of ICT in Schools. All the white papers that constituted this studyʼs main data material reflected strong technology optimism and technology determinism (cf. Bimber, 1990, p. 333). In the wake of this optimism and determinism, a clear ambition for Norway to be ‘among the best in the worldʼ in the use of ICT in schools was also evident in all these white papers. This ambition had already emerged in 1994: ‘The governmentʼs aim of Norway being among the best in the world on the use of ICT in schoolʼ (my italics; Ministry of Church, Education and Research, 1994, p. 33). Furthermore, similar statements about being ‘the best in the worldʼ were regularly included in public documents over subsequent years.

Table 6 Discourse A – Examples: Norway Will Lead the World in the Use of ICT in Schools

|

Example passage |

Source document |

|

‘The governmentʼs aim of Norway being among the best in the world on the use of ICT in schoolʼ. |

Ministry of Church, Education and Research, 1994, p. 33. |

|

‘The Norwegian education system shall be among the best in the world regarding the development of and use of ICT in teachingʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2004, p. 13. |

|

‘The Governmentʼs aim is making the Norwegian school a pioneering school regarding the use of ICT in teaching and learningʼ |

Ministry of Government Administration and Reform, 2007, p. 11. |

|

‘There is razor-sharp international competition to create value through ICT. Therefore, it is important how we facilitate the situation for the individual, for companies and for institutions, so that Norway can be in the first row in the future as wellʼ. |

Ministry of Government Administration and Reform, 2007, p. 10. |

|

‘The fast technological development suggests that we [Norway] all the time must improve to be able to keep up with the bestʼ. |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 23. |

|

‘Norway will be one of the leading countries in the world in terms of the number of citizens who participate digitally, regardless of age, gender, place of residence, education and employmentʼ. |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 15. |

|

‘Norway has been early adopters of ICT in the general population, in business and in public… . A lot of money has been spent on equipping the schools with networks, systems, platforms, teaching aids and digital equipment. The first national digital initiatives in school already came in the 80s. This is likely one of several reasons why Norway is one of the leading countries in the world on the use of the Internet in the populationʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2017–2021, p. 7. |

Note: Italics added by the current articleʼs author.

This studyʼs findings show that, since 1994, political documents have clearly stated that Norway will become ‘among the best in the worldʼ regarding the use of ICT in schools. Such claims regarding the necessity of Norwayʼs becoming a world leader in the use of new digital technology have been proposed as common sense (cf. Fairclough, 2003a, p. 55). Fairclough (2015) explained: ‘Common sense is a form of “everyday thinking” which offers us frameworks of meaning with which to make sense of the world … a popular, easily-available knowledge which works intuitively, without forethought or reflectionʼ (p. 13). Nominalisation was also evident in the reviewed excerpts. Fairclough (2015) described how nominalisation can be recognised in texts: ‘Nominalization … may involve the exclusion of participants in clauses … Nominalization is a resource for generalizationʼ (p. 144). The previous quote also clearly exemplifies what Fairclough (2003a, p. 55) calls value assumptions – that is, assumptions about what is good or desirable. In the current studyʼs context, these value assumptions were ‘world leadingʼ digital development presented as desirable for all Norwegian citizens.

Discourse B: Working Life and Businesses Need Updated Competence. In the introduction to the Solberg I Governmentʼs (H and FrP) strategy plan for 2017–2021, Future, Renewal and Digitalisation, former Minister of Education and Research Torbjørn Røe Isaksen (H) emphasised, ‘Todayʼs technology … will change rapidly in the coming years. Some think we are experiencing a fourth industrial revolution… . We will experience changes where jobs disappear, and people get their everyday life completely alteredʼ (my italics; Ministry of Education and Research, 2017, pp. 2–3). Furthermore, similar statements have appeared regularly in public documents.

Table 7 Discourse B – Examples: Working Life and Businesses Need Updated Competence

|

Example passage |

Source document |

|

‘New knowledge has become the most important force for changes in society, driven forward by large investments in research, development and education. It provides the basis for new professions. For one century ago, “data processing” was not listed in the Oslo catalogʼs Yellow Pages, in 1992 a total of 14 pages agree to various service offers within the industry. At the same time, new knowledge takes the basis away from old professions or changes the content of them, as has happened for the typographersʼ. |

Ministry of Church, Education and Research, 1992, p. 2. |

|

‘Digital competence will increasingly be a competence needed in the years to come in order to participate actively in working and social life. Education at all levels must contribute to creating a good basis for this, and basic education is central to the development of childrenʼs and young peopleʼs digital competence. Through the EEA agreement, Norway participates in the follow-up of the EUʼs ICT work, and for the period 2004ʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2004, p. 48. |

|

‘We must maintain and renew a competitive business life and raise the general and digital competence of the population. It is through good cooperation that we lift each other up, that we create economic growth, create new jobs, and ensures the safety of the majority of us take for grantedʼ. |

Ministry of Innovation and Administration, 2007, p. 9. |

|

‘Norwegian economy and business face significant challenges and our adaptability is put to the test… . Effective use of ICT strengthens businessʼ competitiveness and increase the societyʼs total productivity, this is a prerequisite for the financing of the futureʼs welfare servicesʼ. |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 93. |

|

‘An aging population will present new challenges for access to labour, and lead to changes in the populationʼs demand for goods and services. Competence in the development and use of ICT solutions in the welfare area and in the health and care sector is becoming important for the efficient use of resources in the sectorʼ. |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 31. |

|

‘The Productivity Commission assumes that the oil sector will continue to be important in the Norwegian economy, but that over time Norway will have to base itself on a transition to a more knowledge-based economy. ICT will play an important role in this transitionʼ. |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 29. |

|

‘The productivity development in the Norwegian economy has |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 131. |

|

The EU Commission states … that we are witnessing a new industrial revolution driven by a formidable increase in computing power… . There is a need for an education system that contributes to creating a culture for entrepreneurship and which also promotes entrepreneurial skillsʼ. |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 128. |

|

‘Todayʼs technology … will change rapidly in the coming years. Some think we are experiencing a fourth industrial revolution… . We will experience changes where jobs disappear, and people get their everyday life completely alteredʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2017–2021, pp. 2–3. |

|

‘Working life depends on that the education system delivers workers who are up-to-date, and have the skills and that the competence they need in their professional practiceʼ. |

Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2017–2021, p. 6. |

|

‘ICT is today a prerequisite for innovation and productivity, and central to both the competitiveness of the business world and the welfare services of the futureʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2017–2021, p. 6. |

Note: Italics added by the current articleʼs author.

A principal argument regarding the need for digital innovation has described two conditions for its importance in Norwegian society: the oil crisis and the age wave (cf. Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, pp. 15–16). To solve both challenges, the country must transform from a recourse economy to a knowledge-based economy, and the Solberg I Government emphasised the need for digital innovation and digital solutions which will make the public sector more efficient (cf. Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, pp. 15–16). Statements such as the following have stemmed from this type of description of the future: ‘Working life depends on the education system delivering workers who are up-to-date and have the skills and that the competence they need in their professional practiceʼ (my italics; Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2017, p. 6). This statement argues that Norwegian working life and business productivity, which is a prerequisite for welfare production, are directly linked to an increasing digitalisation of all social arenas. According to Fairclough (2015, p. 38; 2016, p. 85), one here sees interdiscursivity. Words such as innovation, productivity, competitiveness and welfare services appear in a single sentence (cf. Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 6). The quotes, thus, draw on several genres and discourses. They exhibit not only traces of typical capitalist and neoliberal discourse (cf. the use of the signal words innovation, productivity and competitiveness) but also a more traditional term from social democratic discourse: welfare services.

The quotes also refer to several forms of common sense, which appeared consistently in all the documents I reviewed. Such references suggested that society is facing enormous, profound changes due to the rise of digital technology capacity and opportunities. Again, the use of the pronoun we in these education policy documents is strikingly rare. Fairclough (2003b) referred to such descriptions of societal change without an active agent as examples of the cascade of change, explaining: ‘When it comes to processes in the global economy – information, money and services simply “move around the world” apparently under their own steam, and there is no indication of social relations and responsibilities behind these movementsʼ (p. 69). In the current studyʼs documents, capitalism and neoliberalism are undoubtedly the dominant political and economic ideologies (cf. Fairclough, 2015, pp. 29–30) regarding societyʼs digitisation. The documents stressed that Norway must continue to do well as a nation within the capitalist social order to be ‘efficientʼ, ‘productiveʼ, ‘have good access to advanced ICT competenceʼ and have ʼadaptabilityʼ and ‘competitivenessʼ on the world market. Furthermore, the terms work, employment, working life, business and working life and businessesʼ need for updated competence were among the most frequently used in this studyʼs corpus analysis. These terms were mentioned 2,545 times across the documents. My corpus analysis revealed that the terms formation, general education, general knowledge, bildung and the schoolʼs ideal of education were only mentioned 54 times in the same material, while the terms digital formation and digital bildung were only mentioned 13 times. This finding is supported by Haugen and Hestbekʼs (2014) statement that ‘in several important areas of education, the perspective on knowledge is threatened through a neoliberal ideology that has contributed to a narrow view of what education can mean for students and what teacher work is about … overall educational bildung can be in stark contrast to what both teachers and students experience in the field of educationʼ (my italics; p. 1). Stray and Sætra (2015, p. 469) also emphasised that the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Developmentʼs (OECDʼs) influence on Norwegian education policy over the past 15 years has led to a greater focus on digital skills in Norwegian schools. They found that Norwegian curricula and the OECD are very concerned with the demands of working life and linking studentsʼ development to economics and efficiency. Interestingly, the GrunnDig study (2022) found the same political arguments in its analyses on the societal level that I have found in my study concerning the supposed need to digitise the education system. The GrunnDig study states:

It is difficult to address questions about digitisation in and out of school without at the same time drawing lines between the schoolʼs inner life and the society the school is a part of… . At a societal level [emphasis added], there is a clear common thread running through the examined documents, where digitisation is linked to the efficiency of the public sector, innovation, value creation and increased sustainabilityʼ [emphasis added]… . This is expressed through descriptions such as that Norway as a society must utilize the opportunities ICT and the internet provide for value creation and innovation (Meld. St. 27 (2015–2016)). (Munthe et al., 2022, p. 35).

According to Fairclough (cf. 2015, p. 27), international politicians and bureaucrats manage the role of the power behind discourse.

Discourse C: ‘The New Pupilʼ. In the wake of authoritiesʼ focus on the labour market, and both the public sector and businessesʼ need for a highly competent workforce, the white paper Digital Agenda for Norway (2016) by the Solberg I Government (H and FrP) expressed:

The basic education in schools must facilitate for both knowledge about efficient use of ICT and about opportunities to create something with ICT. High quality in ICT … helps to ensure competence and access to new ideas both in business and public sector. (My italics; Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 31)

In this quotation, the Solberg I Government argue for why digital skills should be an integral part of basic education. It states that pupils should learn ‘efficient use of ICTʼ and ‘to create something with ICTʼ (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 31). The thoughts about how basic education should now contribute to ‘ensure competence and access to “new ideas” both in business and public sectorʼ constitute a new vision that had not been present in the earlier white papers included in this study. I first found this idea in NOU 2013:2, Hindrances of Digital Value Creations. This document pointed out a lack of programming competence among the population and a need to enable children and young people to not only manage to use ICT but also ‘create and invent digital content and digital servicesʼ (my italics; cf. Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation 2016, p. 138). Clearly, a shift in Norwegian education policy was evident beginning in about 2013 – authorities stated that pupils should now also be ‘innovators for businessʼ. Pupils are viewed as potential producers who can contribute to new ideas for Norway so that the country can extract maximum yields from the new data-driven economy (cf. Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 95). Similar statements appeared regularly in public documents. The GrunnDig study (2022) also achieved the same findings. Its authors wrote:

That the school and educational and research institutions contribute advanced technological expertise to business and the public sector thus appears as a decisive factor [emphasis added] for whether the digitisation of society in general will have the desired effect. Society will therefore need specialized ICT expertise [emphasis added]. (Munthe et al., 2022, p. 36).

Table 8 Discourse C – Examples: ‘The New Pupilʼ

|

Example passage |

Source document |

|

‘In Digitutvalgetʼs opinion, it is too long to wait until upper secondary education for offers of intermediate teaching in programmingʼ… . Certain countries have taken the societal change to heart. In Estonia, the authorities have decided to teach programming already from the kids start elementary school (Geek.com). Something similar has been advocated in Great Britain. The Norwegian authorities are encouraged to include programming in the curriculaʼ. |

Hindrances of/for Digital Value Creation, NOU 2013, p. 2. |

|

‘The basic education in schools must facilitate for both knowledge about efficient use of ICT and about opportunities to create something with ICT. High quality in ICT … helps to ensure competence and access to new ideas both in business and public sectorʼ. |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 31. |

|

‘There is a lack of programming competence among the population and a need to enable children and young people to not only manage to use ICT but also create and invent digital content and digital servicesʼ. |

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016, p. 138. |

|

‘Programming, or coding, is an important skill that children and young people can learn earlyʼ. |

Ministry of Municipalities and Modernization, 2016, p. 138. |

|

‘In international curriculum development, a stronger emphasis has been placed in several countries on students to master more advanced ICT skills, and more emphasis has been placed on this problem solving and that students understand and produce ICT, rather than be consumers of ICTʼ. |

Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2016, p. 32. |

|

‘To develop an education system that equip pupils and students to deal with a rapidly changing world and educate the future employees to have the competence they need in a labour market means that the basic education must be updated and future-orientatedʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2017, p. 7. |

|

‘Lær Kidsa Koding (LKK) is a voluntary movement… . Local groups and coding clubs have been established all over the country, including at schools, colleges, universities, at companies and in libraries, which offer free courses in programming to children and young peopleʼ. |

Ministry of Municipalities and Modernization, 2016, p. 139. |

|

‘Knowledge, and the ability to apply knowledge, is Norwegian societyʼs most important competitive force… . The education system is the authoritiesʼ most important means of influencing knowledge capital. Developments in working life will largely depend on the ability to utilize new technology that is created outside the countryʼs borders. The ability to learn from other countries is closely linked to the populationʼs overall knowledge and skillsʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2016, p. 5. |

|

‘Productivity growth in Norway depends on the ability to utilize new technology that is largely created outside the country. Employment growth in the past ten years has been particularly strong in knowledge-based industries. A well-educated and adaptable workforce will help ease the costs of adjustment in the economy. This calls for renewal, also in the education systemʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2016, p. 6. |

|

‘The government has launched an experiment with programming … to increasing competence in programming in the school… . The government will also initiate experiments with programming and modelling in secondary educationʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2017–2021, p. 18. |

|

‘If we are to succeed in dealing with the challenges we now face, we must make wise choices. The wisest choice we can make is to invest in knowledge and competence. Shall we develop one school and an education system that equips pupils and students to deal with a world that changes quickly, and help ensure that future employees have the skills they need in a labor market we do not know what looks like, we must ensure that the basic education is updated and future-orientedʼ. |

Ministry of Education and Research, 2017–2021, p. 7. |

Note: Italics added by the current articleʼs author.

Faircloughʼs concept of colonisation (2015, p. 39) became relevant, in this context, in the form of capitalist and neo-liberal ideas about the need for digital innovation and entrepreneurship in business. These ideas have been integrated into pedagogical discourse. Education authorities have signalled that both school praxis and traditional pupil roles will change: ‘To develop an education system that equip pupils and students to deal with a rapidly changing world and educate the future employees to have the competence they need in a labour market means that the basic education must be updated and future-orientatedʼ (my italics; Ministry of Education and Research, 2017, p. 7). This shifting of studentsʼ role towards ‘digital producers and innovators for businessʼ seems to have occurred without much resistance. Selwyn (2010, p. 20) confirmed this point, claiming that the emergence of ICT use in Western education systems has occurred in an ideologically invisible way. Selwyn (2010) stated, ‘This normalization of educational technology over the last twenty years or so into an unquestioning orthodoxy is something that certainly requires scrutiny and reconsiderationʼ (p. 20). Today, programming and coding are compulsory for upper-secondary-school pupils within the core subjects of mathematics and natural science. This change was implemented as part of the LK20. Pupils must also train in computational thinking skills (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2020). In this context, the results of my corpus analysis show that the terms work, employment, working life, business and working life and businessesʼ need for updated competence were used 2,545 times in the documents, while the word pupil was mentioned 283 times. These results show a strong tendency across the education policy documents of focusing not on pupils but – to a far greater extent – on working life, the job market and businessesʼ apparent need for updated competence.

Level 2 Analysis: Discourse Practice – Production and Consumption of Documents

The language used in the white papers, curricula and official reports I studied was characterised by a bureaucratic genre. The documentsʼ tone was impersonal, and their language was sober. Fairclough (2003b) stated, ‘Managerial government is partly managing languageʼ (p. vii). The official documents I analysed aimed to direct Norwegian schools in the years to come. Hence, teachers, educational leaders and school owners will read these official documents as the power behind discourse (cf. Fairclough, 2015, p. 27). Fairclough (2015, p. 28) argued that people with political or economic power, both nationally and internationally – in my research case, politicians and bureaucrats as the senders of the studied texts – contribute to shaping opinions and attitudes about what should be considered common sense in different areas of society.

Level 3 Analysis: Social Practices or Social Structures

The Level 3 analysis of Faircloughʼs model examines the macro-level (Skrede, 2017, p. 32). Fairclough (2003a, pp. 9–10, 218) stated that this analysis concerns the relationship between discourse, power and ideology. Accordingly, I more closely examine the relationship between these three elements in the current subsection. The policy documents I studied frequently argued that the Norwegian business community needs ‘updated ICT skillsʼ because oil will not be a perpetual source of income and because a wave of ageing is underway. Social structures in society are, thus, changing. Norway must, therefore, focus on developing digital competence from which the countryʼs residents can supposedly earn a living in the future (cf. Ministry of Local Government and Modernization, 2016, p. 138; Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2017, p. 6; Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2017, p. 6). The political message is clear: the Norwegian education system must prepare for the future. Todayʼs pupils have, accordingly, been assigned the roles of future digital innovators and entrepreneurs for the business community (cf. Ministry of Education and Research, 2017, p. 7). The Norwegian authorities referred to Schwabʼs (2016) thoughts about the Fourth Industrial Revolution, also called Industry 4.0. (cf. Ministry of Education and Research, 2017, p. 1). This revolution is said to be in its initial stage, whose development and major achievements are expected by 2020–2025. Then, it will enter a new era called Industry 5.0. This period will, allegedly, fully implement artificial intelligence (Kurniawan et al., 2019, p. 156). Fairclough (2006, p. 171) argued that the globalisation discourse of international organisations – for example, the OECD – can be called globalisation from above. He pointed out: ‘Globalization from above is driven by the strategies of powerful agents and agencies, such as those which have adopted the strategy of globalismʼ (Fairclough, 2006, p. 171). The Norwegian authorities have, thus, suggested that individuals (in this research context, pupils) must adapt to societyʼs new structure, which they claim is emerging in order to survive in the labour market (cf. Schwab, 2016, p. 42; Liu, 2014; Siemens 2005; Atwell, 2017). According to Norwegian authorities, the populationʼs digital skills must also be increased to maintain the Norwegian welfare state as citizens know it. Hence, digital skills and competence are considered major objectives in educational programmes and policies. LK20 emphasises the importance of these skills and competence more than The Knowledge Promotion (LK06), and today, several curricula include competence goals related to advanced digital skills, such as programming, coding and algorithmic thinking (cf. The Directorate of Education, 2020). In light of predictions regarding the Fourth Industrial Revolutionʼs consequences on the labour market (cf. Schwab, 2016; Atwell, 2017), a discourse has emerged that describes Norwegian schools as ‘old-fashionedʼ, ‘too traditionalʼ and ‘outdatedʼ (cf. Ministry of Education and Research, 2004, pp. 8–9, 23; Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2007, p. 69; Ministry of Education, 2016, p. 75). My study has shown that the European Union (EU), the OECD, the World Economic Forum, the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise and ICT Norway provide examples of organisations operating as field agents by playing the power behind discourse role (cf. Fairclough, 2015, p. 27) regarding which digital skills pupils should learn in Norwegians schools now and in the future.

Conclusion

In this article, I have identified three discourses that appear dominant in the political argumentation related to Norwegian schoolsʼ focus on ‘digital skillsʼ between 1994 and the launch of LK20. These three discourses are: (a) Norway will lead the world in the use of ICT in schools; (b) working life and businesses need updated competence; and (c) ‘the new pupilʼ. The main findings in my policy-document analysis are that the content and thoughts related to ‘digital skillsʼ in Norwegian upper secondary education appeared to be strongly shaped by a capitalist, neoliberal global discourse, from 1994 to 2020. A clearly cross-political, ambitious discourse emerged, suggesting that Norway should become a ‘world leaderʼ in ICT use in schools. A very important mission for schools, it has been revealed in this studyʼs material, is providing the work and business worlds with an updated, digitally competent workforce to maintain the nationʼs productivity and weather its transformation from a resource economy based on oil production to a knowledge economy based on digital innovations. Around 2013, a new discourse also emerged in the material, suggesting that secondary schools must now socialise students to become ‘innovative digital entrepreneursʼ (cf. Ministry of Education and Research, 2017, p. 7). This political vision suggests that students should develop into innovators and producers who can contribute ideas about new digital products and services to the business world. To foster such studentsʼ development, education policy has strongly argued that schoolsʼ traditional educational activities appear ‘outdatedʼ and ‘too traditionalʼ (cf. Ministry of Education and Research, 2004, pp. 8–9, 23; Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2007, p. 69; Ministry of Education, 2016, p. 75) and must be modernised, that is to say, digitalised.

Litteraturhenvisninger

Antaki, C., Billing, M., Edwards, D., & Potter, J. (2008). Discourse analysis means doing analysis: A critique of six analytic shortcomings. Loughborough Universityʼs Institutional Repository.

Atwell, C. (2017). Yes, Industry 5.0 is already on the horizon. https://www.machinedesign.com/industrial-automation/yes-industry-50-already-horizon

Bimber, B. (1990). Karl Marx and the three faces of technological determinism. Social Studies of Science, 20(2), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631290020002006

Erstad, O. (2010). Digital kompetanse i skolen – en innføring. Universitetsforlaget.

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis. Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2000). New labour, new language? Routledge.

Fairclough, N. (2003a). Analysing discourse. Textual analysis for social research. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203697078

Fairclough, N. (2003b). New labour, new language? Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203131657

Fairclough, N. (2006). Language and globalization. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203593769

Fairclough, N. (2010). Discourse and “transition” in Central and Eastern Europe. In N. Fairclough (Ed.), Critical discourse analysis. The critical study of language (2nd ed., pp. 503–526). Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2015). Language and power. Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2016). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

Haugen, C., & Hestbek, T. A. (2014). Pedagogikk, politikk og etikk: Demokratiske utfordringer og muligheter i norsk skole. Universitetsforlaget.

Haugsbakk, G. (2008). Retorikk, teknologi og læring: En analyse av meningskonstruksjon knyttet til bruk av ny teknologi innen utdanningssystemet [Doctoral dissertation] The Arctic University of Norway.

Jørgensen, M. W., & Phillips, L. (2013). Diskursanalyse som teori og metode (10th ed.). Roskilde Universitetsforlag.

Klausen. (2020). Fra kritt til programmering: En kritisk diskursanalyse av begrepet digitale ferdigheter i norsk utdanningspolitikk og i norsk videregående opplæring [Doctoral dissertation] Inland University].

Kurniawan, A., Komara, B. D., & Setiwan, H.C.B. (2019). Preparation and challenges of Industry 5.0 for small and medium enterprises in Indonesia. Muhammadiyah International Journal of Economics and Business, 1(2) pp. 156–157. https://doi.org/10.23917/mijeb.v1i2

Liu, A. (2014). The laws of cools: Knowledge work and the culture of information. The University of Chicago Press.

Munthe, E., Erstad, O., Njå, M. B., Forsström, S., Gilje, Ø., Amdam, S., Moltudal, S., & Hagen, S. B. (2022). Digitalisering i grunnopplæring; kunnskap, trender og framtidig kunnskapsbehov. Kunnskapssenter for utdanning: Stavanger.

Norwegian Official Report. (NOU 2013:2; 2013). Hindre for digital verdiskapning [Hindrances for/of digital value creation]. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/e2f0d5676e144305967f21011b715c16/no/pdfs/nou201320130002000dddpdfs.pdf

OECD. (2016). Enhancing employability. https://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/employment-and-social-policy/Enhancing-Employability-G20-Report-2016.pdf

Schwab, K. (2016). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. World Economic Forum.

Selwyn, N. (2010). Schools and schooling in the digital age: A critical analysis. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203840795

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 2(1), 3–10.

Skrede, J. (2011). The Oslo Museum Puzzle. Reflections on the relation between culture and economy. FORMAkademisk, 4(1) 2011, 48–64. https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.127

Skrede, J. (2013). The issue of sustainable urban development in a neoliberal age. Discursive entanglements and disputes. FORMAkademisk, 6(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.609

Skrede, J. (2017). Kritisk diskursanalyse. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Stray, H. S., & Sætra, E. (2015). Samfunnsfagets demokratioppdrag i fremtidens skole – En undersøkelse av samfunnsfaglæreres opplevelse av fagets rammebetingelser og Ludvigsen-utvalgets utredninger. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 99(6), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-2987-2015-06-06

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2017). Nye Kunnskapsløftet: Ny overordnet del av læreplanverket [The new knowledge promotion – New overall part]. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/37f2f7e1850046a0a3f676fd45851384/overordnet-del---verdier-og-prinsipper-for-grunnopplaringen.pdf

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2020). Fagfornyelsen [The new knowledge promotion]. https://www.udir.no/kvalitet-og-kompetanse/profesjonsfaglig-digital-kompetanse/utvikle-digital-kompetanse-i-skolen/

The Norwegian Ministry of Church, Education and Research. (1992). Kunnskap og kyndighet. Om visse sider ved videregående opplæring [Knowledge and expertise]. https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1991-92&paid=3&wid=b&psid=DIVL1572&s=True

The Norwegian Ministry of Church, Education and Research. (1994). Om informasjonsteknologi i utdanningen [Information technology in education]. https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/lareplanverket/utgatt-lareplanverk-for-vgo-R94/

The Norwegian Ministry of Education. (2016). Fag-fordypning-forståelse. En fornyelse av Kunnskapsløftet [Subject-specialization-understanding – a renewal of the knowledge promotion]. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/e8e1f41732ca4a64b003fca213ae663b/no/pdfs/stm201520160028000dddpdfs.pdf

The Norwegian Ministry of Education. (2017). Framtid, fornyelse og digitalisering – Digitaliseringsstrategi for grunnopplæringen 2017-2021 [Future, renewal and digitalisation]. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/dc02a65c18a7464db394766247e5f5fc/kd_framtid_fornyelse_digitalisering_nett.pdf

The Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. (2004). Kultur for læring [Culture for learning]. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-030-2003-2004-/id404433/

The Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. (2006). Kunnskapsløftet: Reformen i grunnskole og videregående opplæring [The knowledge promotion (LK06)]. https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kilde/ufd/prm/2005/0081/ddd/pdfv/256458-kunnskap_bokmaal_low.pdf

The Norwegian Ministry of Government Administration and Reform. (2007). Et informasjonssamfunn for alle [An information society for all]. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/25977d684a26494ead8da4106fdd267f/nn-no/pdfs/stm200620070017000dddpdfs.pdf

The Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation. (2016). Digital agenda for Norge [Digital agenda for Norway]. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/fe3e34b866034b82b9c623c5cec39823/no/pdfs/stm201520160027000dddpdfs.pdf

Taylor, S. (2004). Researching educational policy and change in ‘new timesʼ: Using critical discourse analysis. Journal of Education Policy, 19(4), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093042000227483

Tjora, A. (2012). Kvalitative forskningsmetoder i praksis. Gyldendal Akademisk.

van Dijk, T. A. (1990). Social cognition and discourse. I H. Giles & R. P. Robinson (eds.), Handbook of social psychology and language (pp. 163–183). Wiley.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2008). Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory, and methodology. Sage.