«Vi trenger lyd også!» Barn og barnehagelærere skaper multimodale digitale fortellinger sammen

Artikkelen ser nærmere på hva som skjer når to grupper med seks barnehagebarn (4-5-åringer) og én barnehagelærer skaper multimodale digitale fortellinger sammen. Datamaterialet viser at lyden er viktig for barna.

Det er identifisert to hovedtyper av aktiviteter i analysen: ikke-digitale og digitale aktiviteter. Ikke-digitale aktiviteter er f.eks. å dikte fortelling og å lage rekvisitter og kulisser. I digitale aktiviteter spiller digital teknologi en sentral rolle, f.eks. å animere, å fotografere, å redigere, og å ta opp lyd. Det er viktig at ikke-digitale og digitale aktiviteter blir sett i sammenheng og ikke som motsetninger – i skapende prosesser med digital teknologi.

Artikkelen bidrar med kunnskap om hva som skjer når barn og barnehagelærere sammen skaper multimodale digitale fortellinger. Funnene indikerer at barnehagelærernes profesjonsfaglige kompetanse er viktig når barnehagebarn blir involvert i skapende prosesser med digital teknologi. Sammenhengen mellom barnehagelærernes varierte kompetanse og erfaring – bl.a. teknologisk, pedagogisk og faglig kompetanse og erfaring – er sentralt i profesjonsfaglig digital kompetanse.

Det teoretiske rammeverket som brukes i artikkelen er teknologisk pedagogisk fagkompetanse (TPACK) og profesjonsfaglig digital kompetanse.

“We Need Sound Too!” Children and Teachers Creating Multimodal Digital Stories Together

This paper is exploring the technology-mediated creation process when groups of young children (age 4–5) create multimodal digital stories in collaboration with a teacher.

In most contemporary societies there is broad access to a range of digital technologies. However, in the current debate concerning digital technology in early childhood education and care institutions (ECEC), digital technologies are often referred to merely as screens. This paper contributes to the current research by exploring the technology-mediated creation process when groups of young children (age 4–5) create multimodal digital stories in collaboration with a teacher. The theoretical perspectives informing the study are technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) and professional digital competence. The study is a qualitative multiple-case study with two cases. The empirical material consists of video observations of the creation processes, which have been analysed inductively. The analysis shows that recording sound and sharing are the most important for the children. Further, the technology-mediated creation process is characterised by a complex interplay of non-digital and digital activities in which the teachers’ professional digital competence is an important factor.

Introduction

Most children in contemporary societies grow up in cultures with broad access to various digital technologies in their everyday lives (Chaudron et al., 2018; Medietilsynet, 2018). However, in the current debate concerning digital technology in early childhood education and care institutions (ECEC), digital technologies are often referred to merely as screens (e.g., Dahle et al., 2020). Drawing on Burnett and Daniels (2016) and Kucirkova (2014), I consider meaning-making as an entwined activity between on-screen and off-screen activities and traditional and digital resources as complementary resources. Despite an increasing number of empirical studies related to digital technology with children from new-borns to eight-year-olds over the last decade, there have also been calls for more studies focusing on the youngest children’s experiences of creating with digital technology (e.g., Burnett & Daniels, 2016; Hsin et al., 2014; Marsh, 2010) and producing digital stories (Garvis, 2016). This paper contributes to the current research by exploring the technology-mediated creation process when groups of children (age 4–5) create multimodal digital stories in collaboration with a teacher.

Multimodal Digital Stories in ECEC

(Udir, 2017) highlights children’s and teachers’ creative exploration and inventive use of digital technology as a central part of pedagogical practice. Play, learning through everyday activities based on children’s interests, and children’s rights to participate are some of the core values in Norwegian kindergartens (Børhaug et al., 2018; Udir, 2017). According to the framework plan, it is important for children to discover and listen to a variety of stories and expressions as well as to create their own stories. When creating stories, non-digitally and digitally, the children are given opportunities to express their meanings and ideas about matters that are important to them (Udir, 2017).

Kindergartens in Norway are pedagogical ECEC institutions for children ages 0–5. The framework plan is a regulatory framework for the content and tasks of kindergartens.

A multimodal digital story can be defined as a story expressed through different modalities (e.g., voice, gesture, music, pictures and words) and presented digitally (e.g., Kucirkova, 2018; Marsh, 2010). In the previous research, three types of multimodal digital stories created by young children (age 0–8) in collaboration with teachers or researchers in ECEC are found. The first type is digital stories made of pictures and text, for example, children’s drawings or paintings (Letnes, 2014), ready-made images from software or the Internet (Sakr et al., 2016; Skantz Åberg et al., 2015; Wohlwend, 2017), or children’s photographs (Letnes, 2014). The second type is stop-motion animation movies – for example, using two-dimensional drawings (Leinonen & Sintonen, 2014), three-dimensional play materials, or homemade figures (Fleer, 2018; Letnes, 2014; Palaiologou & Tsampra, 2018; Petersen, 2015). The third type is videos of children (Hesterman, 2011). Digital technology introduces new opportunities to the process of creating multimodal digital stories, and can contribute by serving as a resource (Letnes, 2014). The technology makes it easy to modify products during the creation process, for example by changing or deleting elements (Fleer, 2018; Sakr et al., 2016). Digital technology also provides opportunities for adding sound, for example, voice-overs (Fleer, 2018) and creating special effects, for example, flying in a homemade spaceship (Hesterman, 2011). Further, digital technology provides possibilities for children to capture a story and watch it repeatedly as the story develops and as a finished product (Garvis, 2016; Letnes, 2014). A multimodal digital story is also easy to share (Fleer, 2018; Garvis, 2016; Letnes, 2014; Marsh, 2010). When watching their story together with others – for instance, peers or parents – children are given opportunities to experience the multimodal digital story from new perspectives (Letnes, 2014).

The studies included here present various ways of creating multimodal digital stories with young children. However, several of the studies focus merely on digital activities – that is, activities with tablets or computers; less is known about how digital activities are entwined with traditional non-digital activities. Further, the multimodal digital stories presented in the studies are mostly made individually or in pairs, not in groups. The research question in this paper is as follows: What characterises the technology-mediated creation process when groups of young children create multimodal digital stories in collaboration with a teacher?

Theoretical Framework

Pedagogy is considered to be a core knowledge domain in Norwegian ECEC (Børhaug et al., 2018; Udir, 2017). When including digital technology in pedagogical practices, teachers’ knowledge and ability to reflect and make critical choices are crucial (Jernes et al., 2010; Stephen & Edwards, 2018). Such knowledge and ability is , which can be defined as “knowledge about ICT and digital tools related more clearly to children’s cultural formation, bildung, connected to the content, the strategies (working design) as well as values related to the society of tomorrow” (Alvestad & Jernes, 2014, p. 7). In the context of creating multimodal digital stories, I understand pedagogy in terms of the teachers’ aims and reasons for why they create the stories, and digital technology in terms of the methods, how a multimodal digital story is created. Content is related not only to the ECEC curriculum, but also to knowledge of what a multimodal digital story is. This understanding of pedagogy, technology, and content can be seen in line with Mishra and Koehler’s (2006) technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK).

The Norwegian term is profesjonsfaglig digital kompetanse (PfDK).

According to Mishra and Koehler, integrating digital technology in pedagogical practice requires a unique and context-based combination of technology, pedagogy and content. Teachers’ knowledge of the complex interactions among these three knowledge domains, and how to combine them in situ, is central (Mishra & Koehler, 2006). In contrast, the findings from previous studies indicate that teachers’ pedagogical or technological knowledge dominate practice (Jernes et al., 2010; Manfra & Hammond, 2008; Undheim & Vangsnes, 2017). Teachers’ pedagogical aims define their use of technology when creating digital documentaries with students in school (Manfra & Hammond, 2008), and their choices related to content are based on pedagogical justifications when creating digital stories with children in ECEC (Undheim & Vangsnes, 2017). In a study of teachers’ use of digital technology in ECEC, the teachers emphasised their technological knowledge; however, at the same time, they expressed a lack of knowledge of how to include digital technology in their pedagogical practice (Jernes et al., 2010). This is supported by two recent national surveys (Fagerholt et al., 2019, p. 25; Fjørtoft et al., 2019, p. 129), in which Norwegian ECEC practitioners highlight a lack of digital competence as the most limiting factor in their use of digital technology in ECEC. In light of this, teachers’ knowledge of how to combine technology, pedagogy and content in situ – in collaboration with the children during the creation process – is important, as emphasised in professional digital competence and TPACK (Alvestad & Jernes, 2014; Dardanou & Kofoed, 2019; Mishra & Koehler, 2006).

Methods

Research Design

The study is a qualitative multiple-case study with two cases, with a focus on observable contemporary events in situ (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2014), to provide an in-depth exploration of the technology-mediated creation process. In each of the two cases, six children (age 4–5) and one teacher created a multimodal digital story together.

Participants

The participants were recruited from a Norwegian research project (Mangen et al., 2019). Both teachers were female, aged 44 and 47, with 15–20 years of experience as ECEC teachers. One of the teachers had previously made a few multimodal digital stories; however, the other teacher was doing it for the first time. Neither of them had previously used digital technology in a creation process with a group of children over several days. Both teachers expressed that they saw their participation as a good opportunity to learn more about using digital technology with children. To provide the teachers some technical help to get started, they were given the opportunity to attend a workshop focusing on how to create multimodal digital stories on tablets.

Data and Data Collection

The process began with the shared reading of a picture book app as inspiration and ended with a display of the final products. All the activities planned by the teachers during these creation processes are included in the cases. All activities took place in separate rooms, with only the six participating children, the teacher, and I present. The teachers were responsible for the activities while I participated as an observer, taking notes and video-recording the activities. Both cases followed the same case study protocol to maintain the logic of replication and the same chain of evidence, as well as to strengthen the study’s reliability and validity (Yin, 2014). To ensure the quality of the study, a pilot study was conducted.

Based on experiences from the pilot study, all activities were video-recorded to capture the multimodal complexity, the different layers of information occurring simultaneously, and the temporal and sequential records of the process (Flewitt, 2006; Heikkilä & Sahlström, 2003). The activities were recorded with a small, hand-held digital camera with integrated microphone to capture sound, focusing on group activities. I placed myself close enough to capture the interactions between the teacher and the children, the conversations, the body movements, and the artefacts, without interrupting them physically. The video observations were collected over a period of two months; this paper draws on 14 hours of video from 18 days.

Analysis

Both teachers described the creation process by focusing on the activities. Inspired by their descriptions and the creation process in Letnes’s study (2014), I viewed activities as a means of coding what the teachers and children were doing during the process. The videos were analysed inductively through constant comparison analysis, inspired by grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2008), in NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2018). The analysis began with a within-case analysis in which each case was analysed separately, followed by a cross-case analysis with both cases (Creswell, 2013). By drawing on observable data, my aim is to provide an in-depth exploration of the creation process in situ, including the teachers’ comments during the process; however, their reflections of the process are not included. Descriptions of the codes were added to a codebook to ensure consistent coding. The codes were refined and adjusted several times during the analysis, and some were grouped into broader categories; Tables 1 and 2 are the final codebooks.

Table 1 Codebook – Non-digital activities

|

Categories |

Codes |

Description of the code |

|

Narrative |

Activities and conversations concerning the different aspects related to the develop- ment of the narrative |

|

|

Composing |

Conversations about which characters to include in the narrative and what the characters would do |

|

|

Repeating Discussing |

Repeating what they had agreed on, specifying some elements or extending the narrative |

|

|

Re-telling |

Conversations about adjustments during the process from oral to multimodal digital story |

|

|

|

Activities when they were retelling the narrative, e.g. recording the narrator’s voice |

|

|

Props |

Activities and conversations concerning the props |

|

|

Making |

When they were making props, e.g. clay figures |

|

|

Drawing/ painting |

When they were drawing or painting, including conversations about what they were drawing or painting |

|

|

Discussing |

Conversations about what to use as props and how to make them, and what else they needed |

|

|

Planning |

|

Conversations about what they were going to do and when, including questions about who would prefer to do what |

Table 2 Codebook – Digital activities

|

Categories |

Codes |

Description of the code |

|

Animation |

Activities and conversations concerning the different aspects related to making the animations |

|

|

Discussing |

Moving the characters, one step at a time while taking the pictures and creating the animations |

|

|

Preparing |

Preparations with the props and tablet when getting ready to animate the scenes |

|

|

Animating |

Conversations concerning how to animate |

|

|

Pictures |

Activities and conversations concerning the pictures |

|

|

Searching |

Searching for pictures on the Internet and conversations about them |

|

|

Discussing |

Conversations concerning the pictures, e.g. how to take pictures |

|

|

Photograp- hing |

Photographing drawings and text posters |

|

|

Product |

|

Conversations and utterances concerning the products they were making, e.g. when watching the animated scenes, reading the e-book, or listening to the sound recordings |

|

Editing |

Activities and conversations concerning aspects related to editing the e-book or movie |

|

|

Cropping |

Cropping and editing the pictures in the e-book |

|

|

Changing tempo |

Changing the movie’s tempo, in the iMovie app |

|

|

Copying |

Copying pictures, in the Stop Motion Studio app |

|

|

Deleting |

Deleting pictures, in the Stop Motion Studio app |

|

|

Title and text |

Writing and adding text to the e-book and movie |

|

|

Discussing |

Conversations concerning editing |

|

|

Sound |

Conversations concerning sound recordings |

|

|

Recording |

Recording children’s voice and creating a narrator’s voice for the e-book and movie |

|

|

Discussing |

Conversations concerning the recordings, e.g. when listening to the narrator’s voice |

|

|

Adding |

Adding voice recordings and music to the e-book or movie |

|

|

Searching |

Searching for music on the Internet |

|

|

Creating |

Creating their own music, in the Auto Rap app |

|

|

Play |

|

Events when the children spontaneously engaged in play |

|

Technology |

|

Activities and conversations concerning the use of technology |

|

Shared dialogue- based reading |

|

Transcriptions of the shared dialogue-based reading activity |

Ethics

During the research process, I have reflected and thoroughly thought through every aspect. I have been sensitive and flexible, shown respect, and made adjustments as needed in collaboration with the participants. This approach is emphasised by several authors with regard to the practice of being a reflexive researcher (e.g., Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2018; Guillemin & Gillam, 2004). I consider the collaboration between the participants and the researcher to be important in the development and construction of empirical knowledge, which is closely connected to the context and the specific group where the researcher also influences the situation, as noted by Alvesson and Sköldberg (2018). The preliminary findings of the analysis were discussed with the teachers to validate the findings (see Jernes & Alvestad, 2017). The teachers confirmed the analysis of the activities and the creation process.

The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), and all participants provided their informed consent. Trust, loyalty and confidentiality were essential in the interactions between the researcher and participants, both teachers and children. Ethical guidelines, as stated by NESH (2016), were taken into account and followed during the entire research process. The participants’ confidentiality was ensured by anonymising their names and other identifiers.

Results

The participants in the two cases made two different multimodal digital stories (Table 3). In case 1, six children and one teacher made an e-book of drawings, paintings, photos, text, music, songs, and speech called The Wedding. It is about a rooster who is getting married to his dream princess and their large wedding with 12345 guests. In case 2, six other children and their teacher made a stop-motion animation movie with Duplo blocks and clay figures, text, a narrator, and music called Rapunzel. It has clear references to the narrative of Rapunzel, who is trapped in a castle by her stepmother and rescued by a prince.

Table 3 Presentation of the two cases

|

The cases |

Multimodal digital story |

Activities involved |

Technology used |

|

Case 1: The Wedding |

An e-book made of drawings, paintings, photos, written text, music, songs, and narrator voice |

Shared dialogue-based reading, narrative, props, pictures, product, editing, sound, and display of the final pro- duct |

iPad Book Creator (Red Jumper Limited, 2018) Auto Rap (Smule, 2017) YouTube (Google LLC, 2018) |

|

Case 2: Rapunzel |

A stop-motion animation movie made of Duplo and clay figures, written text, narrator voice, and music |

Shared dialogue-based reading, narrative, props, planning, animation, product, editing, sound, and display of the final product |

iPad Stop Motion Studio (Cateater LLC, 2017) iMovie (Apple, 2018) |

Through an inductive approach to the analysis of the video observations, and with a focus on what the teachers and children were doing during the creation process, two main analytical categories were identified: non-digital activities and digital activities. Non-digital activities are activities that occur during the process where digital technology is not used, while digital activities are activities where the use of digital technology plays an important role (see the final codebooks; Tables 1 and 2). The creation process will also be described.

Non-Digital Activities

During the analysis of the video observations, the non-digital activities of narrative, props, and planning were identified.

The narrative activity concerns the various aspects related to the development of the narrative, such as when the teachers and children were discussing which characters to include in the narrative and what the characters would do. In the case of The Wedding, the children and teacher composed the narrative while the children were drawing, indicating an interconnection between the narrative and props activities (Excerpt 1).

Excerpt 1, from The Wedding

The children and the teacher are sitting by the table; the children are drawing props.

Child 1: I’m drawing a princess.

Teacher: What is the princess doing?

Child 1: She is…

Child 2: Getting married to a man.

Child 1: Jumping.

The narrative being composed in Excerpt 1 was continued, and, together, Child 1 and Child 2 decided that the princess was going to jump to another city to marry a man. During the process, the participants reiterated the elements on which they had agreed, specified some elements or extended the narrative, for example, when the character in Excerpt 1 was changed from a man to a rooster. The narrative activity also includes conversations about adjustments in the process from oral to multimodal digital story and the recording of the children’s voices.

Props is an activity performed quite differently in the two cases due to how the multimodal digital stories were produced. The actions included in props are, for example, when a child was making a clay figure to use in Rapunzel, the child said, “The head is going to be yellow, and the body is going to be red.” The props activity includes activities when the children were drawing or painting, scenarios such as when a child said, “I am going to make a cake” and then began to draw. In the beginning of the process, both groups discussed what materials to use to create props and how to make them. Later in the process, the conversations were about which props they had made and what else they needed.

Planning involves discussions about what the children were going to do and when, for example, “On Monday we will make the characters.” The teachers’ questions about who would prefer to do what are also included in this code.

Digital Activities

Several digital activities were identified during the analysis of the video observations, such as animation, pictures, product, editing, sound, and play.

Animation was performed only in the Rapunzel case. When animating the scenes, two or three children collaborated. One or two children moved the characters, one step at a time, while another child took the pictures with the tablet. Animation includes the preparations that are made with the props and tablet when the children and teacher were getting ready to animate the scenes. One day, when they were preparing the props, one of the children suddenly said, “I know what we can use. The sky…,” and went and found a blue mattress. Another child replied, “We need a sky,” and helped to place the mattress against the wall as a background. Then, the children looked at the tablet to see if the mattress looked similar to the sky. The animation activity includes discussions about how to do animation and why. For instance, when one of the children began to move the character before the other children were ready, the teacher explained, “You need to wait, don’t move [the character] before we have started to take pictures, or it won’t show in the movie.”

Events when the children searched for pictures on the Internet and discussed them or when the children photographed their drawings or text posters are coded as pictures (Excerpt 2).

Excerpt 2, from The Wedding

The teacher and children are searching for pictures of weddings on the tablet and have found a picture.

Teacher: What do you think they have done?

Child 1: Got married.

Teacher: How can you tell?

Child 1: They are standing like this. [The child imitates how the couple in the picture is standing.]

Child 2: Because they look beautiful.

The product activity includes discussions and utterances related to the products they were making – for example, when a child suddenly began to talk about the sound while composing the narrative: “We have to change our voice… we cannot talk like we usually talk.” When watching one of the animated scenes for Rapunzel, the teacher described a movement in the movie: “Wow, we can see the trees moving.” “That’s because it’s windy,” one of the children replied. When watching the animated scenes, the children often made comments about the characters’ movements. Questions related to sharing the product are also included in this code – for example, when one of the children asked, “When are we going to show the book to the others?”

Activities when the participants edited the e-book or movie are coded as editing – for example, cropping pictures, changing the movie’s tempo, copying and deleting pictures, and writing titles and text. The children quickly learned how to delete unwanted pictures: “I need to put this one in the trash,” one of the children said when looking through the pictures for Rapunzel. Discussions about editing, how to do it, and why, are coded as editing. When adding text to the pictures for The Wedding, the teacher showed and explained how they could change the size of the letters.

In both cases, sound was the activity the children spoke most about during the process. The children clearly expressed that sound was important, for instance when they were watching an animated scene one of the children expressed, “They don’t talk! We need sound too!” Sound includes events when the children recorded their voices and created a narrator for the e-book and movie and discussions about the recordings – for example, when they were listening to the recorded voices. Sound includes events when the participants added their voice recordings and music to the e-book or movie. “Can you see? It looks like a note. When we see a sign like that, it very often has to do with sound or music,” the teacher said while showing the children where to click to add sound. In the case of The Wedding, they also searched for music on the Internet and created their own music in an app.

Events when the children spontaneously engaged in play – for example, with the drawings or characters – are coded as play. In the case of The Wedding, there were examples of rhyming when the children talked about their drawings while they were drawing. The children also played with the technology, for example when exploring the possibilities of taking photographs with the tablet.

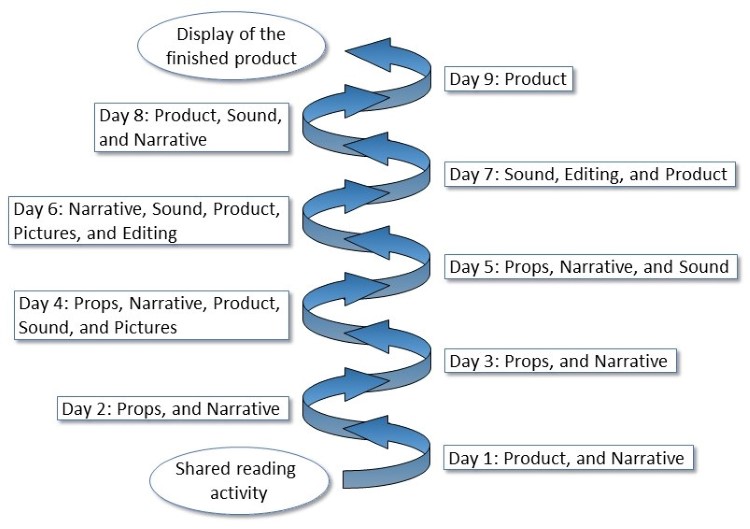

The Creation Process

In both cases, the creation process began with a shared reading activity as inspiration and ended with a display of the finished products. The analysis shows a combination of activities during the nine days of the creation process; see Figure 1. Sometimes the teachers involved the children by explaining what they would do afterwards or the following day, for example: “When we have animated all the scenes, we will do something called editing.” However, during the creation process, both teachers mainly focused on the ongoing activities, and less on the process as a whole.

In the case of The Wedding, the narrative and props activities were often performed at the same time, and the analysis indicates a close connection between these two non-digital activities. There are also close connections between the narrative and digital activities of sound, editing, product, and play in both cases and between narrative and animation in the Rapunzel case. These digital activities inspired and influenced changes and adjustments to the narrative during the process. According to the analysis, there are no clear connections between the non-digital activity of props and the digital activities of pictures, product, and sound. The searches for pictures and music were performed while the children were drawing, which could indicate an interconnection between these activities. However, the searches were mainly done by the teacher while the children were drawing; therefore, I consider these activities to be separate activities that happened to occur at the same time. Later in the process, the children stopped drawing and became involved in the digital activities of pictures and sound together with the teacher.

Analysis of the time spent on the activities during the creation process shows that in both cases, no digital technology was used for approximately 50% of the total time. In the case of The Wedding, the participants spent most time on props (40%), narrative (23%), sound (20%), and product (17%) while in the Rapunzel case, they spent most time on animation (35%), narrative (25%), and props (17%). In both cases, the teacher decided when to use digital technology, and which apps. In the case of The Wedding, the teacher used one of the apps presented in the workshop in addition to a webpage and another app; in the Rapunzel case, the teacher only used apps presented in the workshop (Table 3). Both teachers introduced the tablet as a tool to create by showing the children how to use the apps.

Discussion

Drawing on the previous research on creating multimodal digital stories in ECEC and informed by TPACK and professional digital competence, this paper aims to answer what characterises the technology-mediated creation process when groups of young children create multimodal digital stories in collaboration with a teacher.

Recording Sound and Sharing

For the children, it was especially important to record sound and to share the product. In both cases the teachers made the decision of what they were going to do – for instance, what activity and whether they would use digital technology. However, the observations indicate that some of the choices made by the teachers during the process, for example, regarding sound, were strongly influenced by the children. The utterance, “They don’t talk! We need sound too!” is an example of this. Similarly, in the case of The Wedding, the children clearly expressed that they wanted to create their own music. The pedagogical aspect regarding the activities was dominant in the ways the teachers framed the activities and involved the children; the teachers supported the children’s interests and gave the children time and space to participate and play. The importance of sharing a multimodal digital story with peers is highlighted in previous studies; by showing their finished product to peers or parents, children are given an opportunity to experience the product from new perspectives (Letnes, 2014). However, the findings of this study show that the children also put into words what they see and share perspectives about the product with each other during the creation process, which I interpret as equally important.

Complex Interplay of Non-Digital and Digital Activities

The creation process in both cases can be characterised as a complex interplay of non-digital and digital activities. Some activities took place at the same time without being connected, while other activities took place at the same time and were closely connected. However, the digital technology provided the creation process with new possibilities, as has been emphasised by several researchers (Fleer, 2018; Garvis, 2016; Letnes, 2014; Marsh, 2010). Both teachers introduced the tablet as a tool to create by showing the children how to use some specific apps. The tablet was used for editing, photographing drawings, recording sound, and animation. Thus, at the same time, no digital technology was used for approximately 50% of the total time spent in both cases. This finding highlights the importance of understanding traditional non-digital activities such as narrative and props and digital activities as complementary in the creation of multimodal digital stories, as highlighted by Burnett and Daniels (2016) and Kucirkova (2014). In a technology-mediated creation process, meaning-making occurs as an entwined activity between non-digital and digital activities.

Teachers’ Professional Digital Competence

The findings in this paper highlight the importance of having enough knowledge about digital technology to be able to reflect and make critical choices not only about how to include digital technology in pedagogical practice, but also about when to use technology in activities with the children (Alvestad & Jernes, 2014; Børhaug et al., 2018; Jernes et al., 2010; Stephen & Edwards, 2018). The teachers in this study included technology in a critical and reflexive way by adjusting the use of technology for the children and the activities. This indicates an understanding of how to use technology with the age group, and pedagogic reflections regarding techniques, working methods and equipment (Alvestad & Jernes, 2014; Mishra & Koehler, 2006). Thus, to have knowledge of pedagogy, content and technology is not enough; teachers also need knowledge of how to combine these elements in situ together with the children during the creation process as in professional digital competence and TPACK (Dardanou & Kofoed, 2019; Mishra & Koehler, 2006). Moreover, as also shown in this paper, creating a multimodal digital story can be accomplished without much previous experience in using digital technology with children, as one of the participating teachers was doing so for the first time. Both teachers have many years of experience as ECEC teachers but very little experience in creating multimodal digital stories; thus, they were eager to learn. Further analysis could be conducted to investigate which of the technological experience or the pedagogical experience and motivation is more important.

Conclusion

In this paper, two technology-mediated creation processes are explored and described. The analysis shows that in a creation process in which a group of young children and a teacher use digital technology to create a multimodal digital story, recording sound and sharing are most important for the children. Further, the creation process is characterised as a complex interplay of non-digital and digital activities. The findings in this study highlight the importance of seeing non-digital and digital activities as complementary and entwined activities in the meaning-making. The digital technology – the tablet – played an important role in this creation process by providing possibilities for editing, photographing drawings, recording sound, and animation. The tablet was used as a tool to create.

The study is an example of how two teachers used digital technology to create multimodal digital stories, in two different ways, together with groups of children. The findings draw on observable data and cannot offer any insights about the teachers’ thoughts or reflections regarding their choices related to the creation process. Thus, there is a need for more research on the various aspects related to the creation of multimodal digital stories – for example, how the teachers involved the children and the interactions among the participants.

The findings from this study indicate that teachers’ professional digital competence is an important factor when involving children in a creation process with digital technology, which includes their knowledge of how to use the technology during the process, integrated with pedagogical and content-based judgements and experience (Alvestad & Jernes, 2014; Børhaug et al., 2018; Dardanou & Kofoed, 2019; Jernes et al., 2010; Stephen & Edwards, 2018). Drawing on the results from this study, there is a need for more focus on aspects related to teachers’ professional digital competence in ECEC and teacher education.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to researchers connected to the research project VEBB (Developing a tool for evaluating children’s e-books) for valuable discussions during the process, and to Maryanne Theobald and Natalia Kucirkova for their valuable comments on earlier drafts. However, most of all, great thanks to the two teachers who so willingly welcomed me into their kindergartens.

Litteraturhenvisninger

Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2018). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research (3rd ed.). Sage.

Alvestad, M., & Jernes, M. (2014). Preschool teachers on implementation of digital technology in Norwegian kindergartens. Forum on Public Policy: A Journal of the Oxford Round Table, 2014(1), 1–10.

Apple. (2018). iMovie (Version 2.2.5) [App]. App Store.

Burnett, C., & Daniels, K. (2016). Technology and literacy in the early years: Framing young children's meaning-making with new technologies. In S. Garvis & N. Lemon (Eds.), Understanding digital technologies and young children (pp. 18–27). Routledge.

Børhaug, K., Brennås, H. B., Fimreite, H., Havnes, A., Hornslien, Ø., Moen, K. H., Moser, T., Myrstad, A., Steinnes, G. S., & Bøe, M. (2018). Barnehagelærerrollen i et profesjonsperspektiv – et kunnskapsgrunnlag. Kunnskapsdepartementet.

Cateater LLC. (2017). Stop Motion Studio (Version 8.4.1) [App]. App Store.

Chaudron, S., Di Gioia, R., & Gemo, M. (2018). Young children (0–8) and digital technology: A qualitative study across Europe [EUR 29070]. European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/294383

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Dahle, M. S., Hodøl, H.-O., Kro, I. T., & Økland, Ø. (2020). Skjermet barndom? Rapport basert på undersøkelse blant foreldre og lærere om barns skjermbruk. Barnevakten.

Dardanou, M., & Kofoed, T. (2019). It is not only about the tools! Professional digital competence. In C. Gray & I. Palaiologou (Eds.), Early learning in the digital age (pp. 61–76). Sage.

Fagerholt, R. A., Myhr, A., Stene, M., Haugset, A. S., Sivertsen, H., Carlsson, E., & Nilsen, B. T. (2019). Spørsmål til Barnehage-Norge 2018: Analyse og resultater fra Utdanningsdirektoratets spørreundersøkelse til barnehagesektoren. Trøndelag forskning og utvikling.

Fjørtoft, S. O., Thun, S., & Buvik, M. P. (2019). Monitor 2019: En deskriptiv kartlegging av digital tilstand i norske skoler og barnehager. Sintef.

Fleer, M. (2018). Digital animation: New conditions for children's development in play-based setting. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(5), 943–958. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12637

Flewitt, R. (2006). Using video to investigate preschool classroom interaction: Education research assumptions and methodological practices. Visual Communication, 5(1), 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357206060917

Garvis, S. (2016). Digital technology and young children’s narratives. In S. Garvis & N. Lemon (Eds.), Understanding digital technologies and young children (pp. 28–37). Routledge.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

Google LLC. (2018). YouTube (Version 13) [Web Page]. https://www.youtube.com

Guillemin, M., & Gillam, L. (2004). Ethics, reflexivity, and “ethically important moments” in research. Qualitative Inquiry, 10(2), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800403262360

Heikkilä, M., & Sahlström, F. (2003). Om användning av videoinspelning i fältarbete. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 8(1–2), 24–41.

Hesterman, S. (2011). Multiliterate Star Warians: The force of popular culture and ICT in early learning. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 36(4), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911103600412

Hsin, C.-T., Li, M.-C., & Tsai, C.-C. (2014). The influence of young children's use of technology on their learning: A review. Educational Technology & Society, 17(4), 85–99.

Jernes, M., & Alvestad, M. (2017). Forskende fellesskap i barnehagen – utfordringer og muligheter. In A. Berge & E. Johansson (Eds.), Teori og praksis i barnehagevitenskapelig forskning (pp. 71–84). Universitetsforlaget.

Jernes, M., Alvestad, M., & Sinnerud, M. (2010). “Er det bra, eller?” Pedagogiske spenningsfelt i møte med digitale verktøy i norske barnehager. Nordisk Barnehageforskning, 3(3), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.280

Kucirkova, N. (2014). iPads in early education: Separating assumptions and evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00715

Kucirkova, N. (2018). How and why to read and create children’s digital books: A guide for primary practitioners. UCL Press.

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2008). Qualitative data analysis: A compendium of techniques and a framework for selection for school psychology research and beyond. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.587

Leinonen, J., & Sintonen, S. (2014). Productive participation - children as active media producers in kindergarten. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 9(3), 216–236.

Letnes, M.-A. (2014). Digital dannelse i barnehagen: Barnehagebarns meningsskaping i arbeid med multimodal fortelling. (Doctoral dissertation). Norges teknisk-naturvitenskaplige universitet, Trondheim, Norway.

Manfra, M. M., & Hammond, T. C. (2008). Teachers’ instructional choices with student-created digital documentaries: Case studies. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 41(2), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2008.10782530

Mangen, A., Hoel, T., Jernes, M., & Moser, T. (2019). Shared, dialogue-based reading with books vs tablets in early childhood education and care (ECEC): Protocol for a mixed-methods intervention study. International Journal of Educational Research, 97, 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.07.002

Marsh, J. (2010). Childhood, culture and creativity: A literature review. Creativity, Culture and Education.

Medietilsynet. (2018). Foreldre og medierundersøkelsen 2018: Foreldre til 1–18-åringer om medievaner og bruk. Medietilsynet.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

NESH. (2016). Guidelines for research ethics in the social sciences, humanities, law and theology (4th ed.). The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees.

Palaiologou, C., & Tsampra, E. (2018). Artistic action and stop motion animation for preschool children in the particular context of the summer camps organized by the Athens Open Schools Institution: A case study. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 17(9), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.17.9.1

Petersen, P. (2015). “That's how much I can do!” Children's agency in digital tablet activities in a Swedish preschool environment. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 10(3), 145–169.

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo 12 Pro (Version 12.3.0.599; 64-bit) [Software]. https://www.qsrinternational.com

Red Jumper Limited. (2018). Book Creator (Version 5.1.10) [App]. App Store.

Sakr, M., Connelly, V., & Wild, M. (2016). Narrative in young children's digital art-making. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 16(3), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415577873

Skantz Åberg, E., Lantz-Andersson, A., & Pramling, N. (2015). Children’s digital storymaking: The negotiated nature of instructional literacy events. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 10(3), 170–189.

Smule. (2017). Auto Rap (Version 2.3.5) [App]. App Store.

Stephen, C., & Edwards, S. (2018). Young children playing and learning in a digital age: A cultural and critical perspective. Routledge.

Udir. (2017). Framework plan for kindergartens. The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

Undheim, M., & Vangsnes, V. (2017). Digitale fortellinger i barnehagen. Nordisk Barnehageforskning, 15(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.1761

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.