Et økokritisk perspektiv på friluftslivelevenes forhold til naturen

Ved å satse på utdanning for bærekraftig utvikling, kan utdanningsprogrammer i friluftsliv legge til rette for et økosentrisk skifte i forholdet menneske-natur, som uten tvil er en underliggende årsak til naturkrisen.

Friluftslivfaget bør utdanne for bærekraftig utvikling som svar på naturkrisen. Ved å satse på utdanning for bærekraftig utvikling, kan utdanningsprogrammer i friluftsliv legge til rette for et økosentrisk skifte i forholdet menneske-natur, som uten tvil er en underliggende årsak til krisen. Denne artikkelen søker ny innsikt i friluftslivstudentenes forhold til naturen gjennom hva de sier om eget friluftsliv. Artikkelen tar sikte på å gi kritisk innsikt i hvordan friluftsliv og undervisning utendørs kan føre til mer bærekraftige forhold til naturen. Empirien består av åtte intervjuer analysert innenfor rammen av posthuman og økokritisk teori.

Funnene indikerer at studentene i denne studien har dannet et antroposentrisk forhold til naturen innenfor en natur-kultur-dikotomi. Selv om studentene i studien er miljøbevisste, ettersom de bygger sitt forhold til naturen innenfor en natur-kultur-dikotomi, holder de seg ikke ansvarlige utover sitt eget private forhold til naturen. Følgelig opplever disse studentene spenninger innenfor natur-kultur-dikotomien mellom deres økologisk bevisste forhold til naturen og deres antroposentriske syn på naturen.

Friluftslivsfaget bør synliggjøre sitt forhold til naturen og kritisk undersøke hvordan det representerer naturen gjennom pedagogisk praksis.

An ecocritical perspective on friluftsliv students’ relationships with nature

By aiming for education for sustainable development, friluftsliv education programmes could facilitate an ecocentric shift in the human–nature relationship that is arguably an underlying cause of the crisis facing the natural world.

Friluftsliv (“free-air life”) and outdoor education programmes should educate for sustainable development in response to the crisis facing the natural world. By aiming for education for sustainable development, friluftsliv education programmes could facilitate an ecocentric shift in the human–nature relationship that is arguably an underlying cause of the crisis. This article seeks new insight into friluftsliv students’ relationship with nature through their reports on their own friluftsliv. The article aims to provide critical insight into how friluftsliv and outdoor education may lead to more sustainable relationships with nature. The empirical work consists of eight interviews analysed within a framework of posthuman and ecocritical theory.

The findings indicate that the friluftsliv students in this study have formed an anthropocentric relationship with nature within a nature–culture dichotomy in their own friluftsliv. Although the students in this study are environmentally conscious, as they are building their relationship with nature within a nature–culture dichotomy, they do not hold themselves accountable beyond their own private relationship with nature. Consequently, these students experience tension within this nature–culture dichotomy between their ecologically aware relationship with nature and their anthropocentric view of nature.

Friluftsliv and outdoor educational programmes should make their relationships with nature explicit and should critically examine how they represent nature through educational practice.

Introduction

The world is facing collapsing ecosystems, climate crises, and rapidly shrinking biodiversity (IPBES, 2019), crises behind which human influence is a primary driver (IPCC, 2021). The United Nations Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development (UNECE, n.d.) highlights participatory and transformative education as a critical element in creating a more sustainable society (see also Straume, 2020). According to Loynes (2018, p. 29), more and more educators around the world are consciously designing outdoor education programmes that are transformative in terms of environmental issues. Scholars in Norway argue that friluftsliv education programmes should (continue to) address climate change and the ecological crisis as being the most critical problems facing society today (Breivik, 2020; Leirhaug et al., 2019).

The Scandinavian notion of friluftsliv (literally “free-air life”) has become familiar beyond Scandinavia as an exceptionally environmentally friendly form of outdoor recreation and education. The deep ecology movement strongly influenced the beginnings of friluftsliv education in Norway in the 1970s (Breivik, 2020; Leirhaug et al., 2019). As such, the Norwegian tradition of friluftsliv education has a normative value base in terms of relationships with nature and environmental responsibility. Normative friluftsliv education advocates for a personal experience of nature in which the individual seeks a deeper connection with nature and becomes an ecologically conscious citizen (Leirhaug et al., 2019).

At this point, it is necessary to note that friluftsliv education is also an arena with conflicting values. Gelter (2010) claims that global and commercial influences have created a divide between traditional value-driven friluftsliv and modern friluftsliv. On the one side is traditional normative friluftsliv with its deep ecological values. On the other is the neo-liberal “performance code” focusing on skills and performance in nature (Backman, 2011, p. 284). In a study of representations of nature in Norwegian teacher education, Hallås et al. (2019) have found an instrumentally oriented friluftsliv with only one mention of friluftsliv to link it to ecological values. Similarly, in his study of friluftsliv education in Swedish schools, Mikaels finds that friluftsliv has been “reduced” to activities and skills in a natural context (2017, pp. 29–30). Whatever the underlying values of friluftsliv and outdoor education programmes, a commonality is that they revolve around nature experiences and can potentially address sustainable relationships with nature.

A common assumption when linking friluftsliv and outdoor education to environmental issues is that the personal experience of nature will lead to citizens who are more environmentally conscious and responsible, as seen in the Norwegian government’s latest white paper on friluftsliv (Meld. St. 18 (2015–2016)). Research suggests that experiences with nature that engage the participant’s emotions, compassion, and sense of meaning have a greater chance of bringing about environmentally responsible behaviour (Lumber et al., 2017). Chawla (2006) argues that the quality of the experience and with whom the experience is shared influences the potential for a person to become more environmentally responsible. Research suggests that nature experiences become more profound when people engage with nature through hands-on activities such as craft making (Haukeland & Sæterhaug, 2020). In addition, becoming environmentally accountable seems to be a lifelong process rather than a “quick fix” with one-time nature experiences (Chawla, 2006; Martin, 1996).

Furthermore, the empirical evidence of a connection between personal experience and environmental accountability is not wholly convincing. Høyem (2020) shows that environmental awareness does not equate to environmentally responsible behaviour. Through a series of interviews with outdoor recreationists, Høyem discovered that informants shared the conviction that nature experiences could lead to environmentally responsible behaviour, although their conduct did not reflect environmental consciousness. In their recent literature review, Gruas et al. (2020) found that the majority of the 47 publications surveyed show outdoor recreationists to have a low level of awareness of the environmental impact of their activity in nature. An earlier study on Norwegian leisure activities found friluftsliv to be one of the leisure activities with the greatest environmental impact (Hille et al., 2007). The assumption that nature experiences should lead to more environmentally conscious actions despite (some) nature experiences having a high environmental impact means that there is a sustainability paradox in friluftsliv (see Gurholt & Haukeland, 2019). Furthermore,Aall et al. (2011) have found that while experience with nature drives outdoor recreation in Norway, the nature experience is increasingly mediated by cultural artefacts such as cars, cabins, and leisure boats.

In this article, I take the stance that friluftsliv and outdoor education should engage in education for sustainable development. As students are future practitioners in this field, I find their perspectives particularly interesting. Current research lacks a student perspective on sustainability, the relationship with nature, and nature experiences within the contexts of friluftsliv and outdoor education in higher education. Therefore, this article seeks to answer the following research question: How is friluftsliv students’ relationship with nature formed through their friluftsliv? This article is part of a more exhaustive study exploring friluftsliv students’ relationship with nature through their reports on their own friluftsliv and friluftsliv education.

I have used qualitative interviews to investigate friluftsliv students’ relationships with nature within the context of their own friluftsliv. The scope of the article is not to generalise to all friluftsliv students in the various educational programmes in Norwegian higher education, but I do aim to provide an analytical transferability of relationships with nature by way of posthuman and ecocritical concepts. In doing so, I hope to make a novel contribution to the friluftsliv and outdoor practitioners who want to educate for sustainable relationships with nature.

Conceptual and analytical framework on human–nature relationships

Ferrando (2016) argues that it is not enough to address the symptoms of environmental challenges: we need to address the underlying cause – our anthropocentric relationship with nature. In this study, I look to ecocriticism and posthumanism to inform my understanding of human–nature relationships. A posthuman understanding of the human–nature relationship opposes the Cartesian dichotomies found in the anthropocentric humanities (Braidotti, 2013). Barad (2007, p. 160) argues for a flattened ontology in which the more-than-human and human world are intra-actively entangled. Intra-active implies being a part of and acting from within, in contrast to inter-active, which refers to influence between groups and ecologies. As such, the posthumanist subject is embedded in and intra-acting with human and more-than-human ecologies (Braidotti, 2019, p. 45). In other words, relationships between humans and nature are relationships no different from human–culture relationships. Nature and culture represent different environments, but they are not opposites.

The anthropocentric human–nature relationship in modern society has led to an understanding of nature as a resource exploitable for human culture (Braidotti, 2013; Vetlesen, 2015). Humans have rationalised and justified overconsumption of the natural world as a result of understanding nature and culture as two distinct worlds. I understand nature and culture not as dichotomies but as part of a posthumanist nature–culture continuum of environments and relationships. Understanding our existence as embodied and embedded in ecologies of nature and culture makes us as humans accountable and responsible for our actions and relationships with nature (Barad, 2007; Braidotti, 2013).

Ecocriticism and the NatCul Matrix

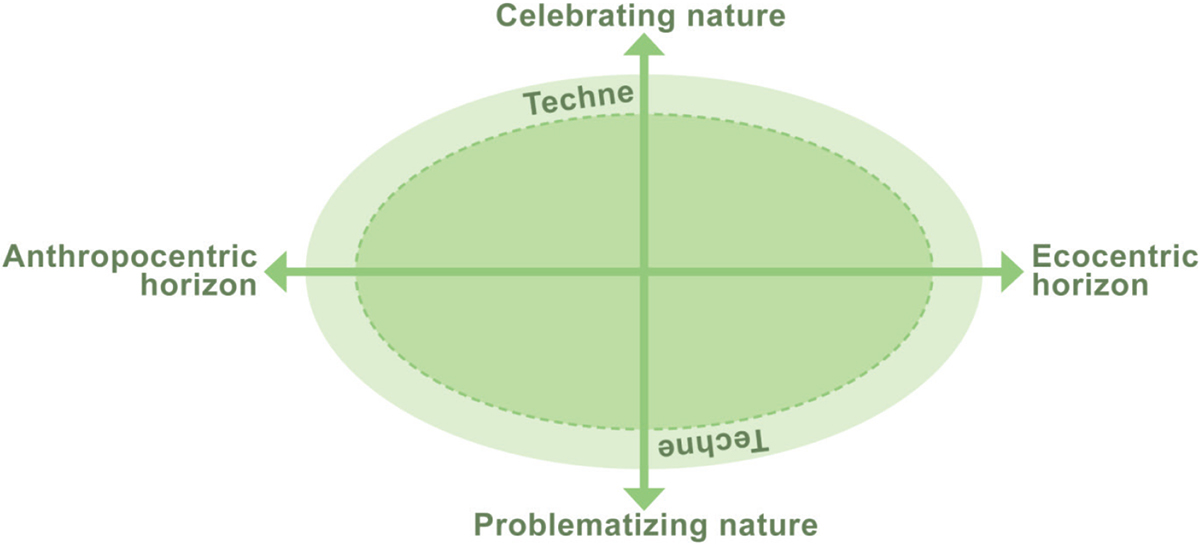

Influenced by the posthuman concept of the nature–culture continuum, Goga et al. (2018) developed the Nature in Culture Matrix (NatCul Matrix) as an analytical and conceptual tool for ecocritical research. Ecocriticism is the study of how nature is represented in culture (Garrard, 2012; Goga et al., 2018). On the horizontal axis of the matrix, nature representations can be identified along a continuum with anthropocentric and ecocentric horizons. The vertical axis of the NatCul Matrix allows for discussion of portrayals of nature on a continuum from celebration to problematisation. The two continuums in the NatCul Matrix allow for a critical deconstruction of nature representations and nature tropes on every day and ontological levels (Goga et al., 2018).

In ecocriticism, nature tropes refer to typical representations of the human–nature relationship in literature. Nature tropes are literary images, metaphors, and common concepts that are recurring themes used to understand nature. According to Garrard (2012), some of the best-established tropes in nature writing and ecocritical literature are the pastoral, wilderness, apocalypse, and dwelling tropes. Below, I will place the four nature tropes in the NatCul Matrix and give examples that are relevant to friluftsliv.

In her PhD thesis, Kloet (2010) examines how nature is represented in outdoor recreational writing in Canada. Kloet shows how wilderness can be associated with both celebrating and problematising views of nature. The wilderness trope can be found in the romantic roots of friluftsliv in the late 1800s and early 1900s, where overcoming challenges in remote nature could be seen as a rite of passage for bourgeois men (Gurholt, 2008). At the same time, pastoral can be understood to mean pristine and idyllic in outdoor recreational contexts. The pastoral and the idyllic wilderness tropes are associated with a tourist’s perspective with romantic understandings of the aesthetic beauty of nature (Garrard, 2012, p. 117). These tropes build on the dichotomy between nature and culture, where the human being, representing culture, visits natural environments but is never seen as part of nature (Beery, 2014). As such, both pastoral and wilderness tropes are anthropocentric and mostly celebratory in the context of friluftsliv.

The apocalypse trope in ecocriticism problematises the relationship between humans and nature by referring to environmental catastrophes and the end of human civilisation. It invokes a sense of responsibility for preventing the catastrophic implications of an anthropocentric relationship between humans and nature. Using this nature trope, one acknowledges the negative influence of anthropocentric human activity on nature. Nature is closely linked to the human world and to how human activity influences ecosystems in which humans partake in apocalyptic tropes. There is interaction between nature and culture in this trope. Apocalyptic tropes in friluftsliv may be anthropocentric and include how littering and pollution ruin a nature experience. Apocalyptic tropes may also have a ecocentric angle and problematise friluftsliv with regards to nature itself.

Lastly, the dwelling trope refers to an ecocentric intra-active relationship between humans and nature. Garrard (2012, p. 117) shows how the dwelling trope in literature can represent relationships where an intra-active influence on nature is key, both celebrating and problematising the relationship. Celebratory elements of the dwelling trope are found in a traditional, normative understanding of friluftsliv as an alternative way of life. When Næss says that friluftsliv is a way of life, he is suggesting a deeper connection with nature where he is not an observer but a part of the natural ecosystems of his environment (Næss, 1999, p. 367). This trope depicts nature not as a place to visit but as the environmentally accountable human’s home. Martin (1996) shows that nature is seen as a subject and part of the self in the dwelling trope.

Surrounding the matrix is a concept referred to as “techne”. Techne is the idea that technology and culture mediate nature experiences. For example, techne can be understood as the mediating artefacts that Aall et al. (2011) found to be increasingly related to the nature experience. These mediating artefacts affect the nature experience and the human–nature interaction, in both an enabling and a lessening sense. Cultural norms, ideas, and understandings are an expression of techne and mediate an understanding of nature and the nature experience in friluftsliv. For example, a rock climber and sheep farmer may have different understandings of the same alpine mountain landscape. The jagged peaks may invoke a celebratory understanding in the rock climber, who is looking for inspiring routes and climbing opportunities. By contrast, the sheep farmer may problematise the landscape, fearing for the sheep as they wander the landscape.

When studying texts and oral accounts, techne also has a hermeneutic function in that it reminds the reader and the listener that the views and values communicated by friluftsliv students are mediated and interpreted within a research context.

Method

I have used qualitative interviews to investigate friluftsliv students’ relationship with nature through their reports on their own friluftsliv. Our language helps to shape our relationships with nature and the natural environment (Beery, 2014; Ferrando, 2016; Goga, 2016). Therefore, investigating how friluftsliv students characterise nature in spoken language can help us to understand the informants’ relationship with nature and provide further insight into the human–nature relationship in friluftsliv. The narratives and conceptual statements in the interviews reveal the students’ particular understanding of their relationship with nature.

Informants

I recruited eight friluftsliv students from two universities in Norway that were conveniently accessible to me as the researcher. At both universities, four students volunteered in response to an invitation issued to third-year students on the friluftsliv bachelor’s degree course. The eight informants were 23 to 41 years of age and included four females and four males. Four of the informants were Norwegian and the other four were European of various nationalities. The informants have been anonymised and given generic names in this article. It is worth mentioning that the educational programmes at both universities include courses that touch directly on the relationship with nature and on sustainability in friluftsliv. However, it is not my aim to investigate how each student’s education has influenced their relationship with nature. This study nevertheless takes a step towards educators and future practitioners in the field having a better understanding of nature within the context of friluftsliv.

The informants were informed of the purpose of the study, and they provided written consent for the interviews to be recorded. During the interviews, video and audio recordings were made using Zoom and stored on a secure research server. The Norwegian Centre for Research Data approved the handling of personal information in the study (NSD, reference code: 194047).

Design and interview procedures

The interviews were conducted over the internet using Zoom as the interview medium to enable video and voice communication. I completed two pilot interviews in the first half of May 2020 to evaluate Zoom as an interview medium and test the interview procedure. I made substantial changes after these pilot interviews; these interviews are not included in the study. I conducted the eight interviews included in the study in May and June 2020. The interviews lasted approximately one hour each.

I developed a good rapport with all of the informants, in part because they were able to participate in the interviews from home and, as such, felt comfortable in the interview setting (see Lo Iacono et al., 2016). In one of the interviews, the informant had issues with his web camera. However, this did not affect our rapport during the interview, and I have included the interview in the study.

The interview procedure included two elicitation tasks that the informants performed before the interview. I also had an interview protocol, which served as a loose guide to topics and a reminder as I probed and asked follow-up questions. In addition to a brief introduction to the study and a warm-up in which the informants were asked to introduce themselves, the interview comprised two main sections. According to the first section of the interview protocol, I probed the informants’ friluftsliv and their relationship with nature; this was linked to a photo-elicitation task. The informants had produced two or three photographs depicting their friluftsliv and their relationship with nature for the photo elicitation task. This part of the interview was driven by the stories that the photos elicited from the informants.

The second section related to a second elicitation task and explored the informants’ experience of nature representations in their friluftsliv education. The second elicitation task required the informants to read a short newspaper article by Faarlund (2020) in which he criticises friluftsliv programmes and educators as being passive in terms of the sustainability paradox in friluftsliv. This part of the interview followed a more traditional questioning structure regarding the informants’ reactions to the second elicitation task and their own experience of sustainability and nature representations in their educational programme. For the purposes of this article, the main analytical section was the photo elicitation and the conduct of interview protocol relating to the students’ own friluftsliv and their relationship with nature.

I chose to utilise photo elicitation in the interviews to contextualise the informants’ relationship with nature. According to Harper (2002), photo elicitation interviews are well suited to establishing a shared understanding and to bridging the gap between the researcher and the informant. I further believe, as Harper argues, that photo elicitation is better at generating information with a link to emotions, memories, and profound thoughts than interviews do on their own. Using photos to elicit the informants’ own experiences and information about events in their lives gives the interviews a narrative nature. The photos in this study were either taken by the informants themselves or else the informants were in the photos. For example, one informant’s first photo showed a drawing of a mountain scene and an inspirational quote. The rest of his photos were photos of nature and various forms of friluftsliv activity. However, as Pink (2013) emphasises, the use of photo elicitation must not be understood as a method for extracting information. Instead, the photos provide context and a backdrop to the anecdotes elicited by the photos. As such, the photos themselves are not part of the analysis for this article.

Ecocritical analyses

I used Nvivo 12 (QSR International Ply Ltd, 2020) to transcribe and analyse the interviews. I analysed the interviews by conducting close re-readings and by thematically coding ecocritical tropes and affective statements on the students’ friluftsliv and their relationship with nature. To avoid “quasi-statistical coding” that would decontextualise the informants’ stories (see Pleasants & Stewart, 2020, p. 12), I mapped the codes for each informant in the NatCul Matrix. By visually mapping these in the NatCul Matrix, I obtained a sense of the thematic content of the interviews without reducing the informants’ relationships with nature to limiting codes and themes. Not carrying out coding for the informants as a whole at this stage allowed me to pursue a more thorough understanding of the individual informants’ relationship with nature.

Once I understood each informant’s relationship with nature as well as possible, I analysed the informants together in order to identify recurring themes and emerging differences. I focused on the recurring tensions that emerged in the students’ relationships with nature through their friluftsliv.

Findings and discussion

The students in this study chose various approaches to present their friluftsliv and their relationship with nature. Some of the students shared structured narratives with overarching plots; others highlighted specific aspects of their relationship with nature. In the interviews, the students shared both concrete experiences and generalisations of their friluftsliv and their experience of nature. In analysing the interviews, I identified two common tensions in the informants’ relationships with nature. Firstly, the informants’ friluftsliv occurs within a state of tension between nature and culture. Secondly, the informants experience tension between the values and actions relating to sustainability in friluftsliv.

Friluftsliv in nature–culture tensions

Although the eight informants have multifaceted relationships with nature through varied friluftsliv activities, I identified some commonalities. At the core of all eight informants’ rationale for their friluftsliv is a celebratory notion of nature as pastoral and as an idyllic wilderness. The informants all contrasted time spent in nature through friluftsliv with the life they lead in the cultural world. By using the celebrating nature tropes of idyllic wilderness and the pastoral, the informants problematise culture and romanticise nature. Frode, when sharing a picture of a solo ski expedition that lasted almost two weeks, exemplifies how a sense of wilderness allows a more profound connection with nature and disconnection from culture.

Frode: Being alone in nature lets me get so much closer to nature. Solitude is a gateway for me to come into close contact with nature and take it all in. Nature is awesome. Being alone in the wilderness is a way to get that feeling, but I will say that I can also get the same feeling when I am close to town and I sit at a bonfire. I find the presence and connection easier on longer trips, but I can also find it on short trips.

Some students say that they intentionally use friluftsliv to disconnect from the business of their everyday lives and (re)connect with simpler life in nature. As Hilde exemplifies:

Hilde: When I am out like that, just being out, I feel that I am doing something, and I have a plan for what I should do, and everything else I don’t have to think about.

Hilde describes feeling that she does not meet the expectations she sets for herself in everyday life. Arne has similar feelings. He portrays his “normal life” in society and contrasts this with the sense of peace he obtains through his friluftsliv:

Arne: I think the competitive and aesthetic sides of it are important to me.

Interviewer: How is this important to you? How does this show?

Arne: I think it is closely related to living in nature for a little longer than just one day. It may have to be a little more than a day. I often feel that when you are out more than a day, your rhythm goes down a bit, so you notice some more details, and you forget time and place.

Interviewer: Would you say that you are more anchored when in nature?

Arne: Yes. Yes, I think when you are out, life is much easier. (…) There are many things that I do not quite understand about how it works in society. So, in many ways, what happens in society is much more complex than [what happens] when we are out in nature, and it is very concrete and straightforward in several ways.

The quotes from Frode, Hilde, and Arne exemplify the disconnect between the natural and cultural worlds that I found at the heart of all of the informants’ friluftsliv. The students use wilderness and pastoral tropes that separate nature and culture from each other and which are anthropocentric at the core. As such, the students reveal a nature–culture dichotomy in their rationale for their friluftsliv. The dichotomy between life in human culture and life in nature is at one and the same time the tension driving their friluftsliv and the resolution of that tension. The further from culture the informants get, the more connected they feel with nature. The experience of connection with nature in the students’ friluftsliv nevertheless seems fragile. Several of the informants said that powerlines, roads, cabins, and the tracks of other skiers in the area seemed to undermine their romantic notions of wilderness and the pastoral.

Interviewer [referring to David’s photo of himself ski mountaineering with a snow-covered mountain landscape in the background]: What role does nature play in these experiences?

David: It plays a huge role. It is, in a way, the backdrop, you could say. But, on the other hand, it is the whole thing. I feel more and more that the longer I am away from human constructs, the deeper the experience [of nature].

Interviewer: Yes.

David: If I am on a trip, as in the photo, and I see a powerline going through the valley or over the mountain, I think it is pretty disturbing.

(…)

David: I think it is a little like these human encroachments are more reminiscent of violations than encroachments in some situations.

David exemplifies what several informants discussed in terms of seeking wilderness untouched by other humans. The wilderness and pastoral tropes relate to disconnecting from culture and reconnecting with nature. The informants portray themselves as visitors in nature before returning home to culture. According to Garrard (2012, p. 63), wilderness is a romantic notion wherein the individual seeks “nature as a stable, enduring counterpoint to the disruptive energy and change of human society”. Through wilderness and pastoral tropes, the informants celebrate nature as an unchanging contrast to culture’s “constructed reality”. Beery (2014) warns that the notion of wilderness as untouched land creates artificial boundaries between people and the world in which they live. This seems paradoxical when the informants talk of wilderness as a place of connection with nature. By living in a nature–culture dichotomy, the informants feel connected with a romantic notion of nature while simultaneously creating separation between their friluftsliv and their cultural lives.

The informants depict nature as a pastoral and as idyllic wilderness in stark contrast to the cultural environment of everyday life. The informants’ sense of peace and belonging in nature fades once they return to culture. Scrutiny of the informants’ friluftsliv and their relationship with nature within the NatCul Matrix shows that the nature–culture dichotomy is a techne that mediates their nature experience. The mediation of the nature experience within this nature–culture dichotomy imposes constraints on their friluftsliv and their relationship with nature. The techne of separation from nature as found in the nature–culture dichotomy cannot foster the accountability of an intra-active relationship with nature.

Ferrando (2016) argues that separating the human cultural world from the natural world is the cause of the anthropocentric relationship between humans and nature. Consequently, I suggest that understanding friluftsliv as an escape from culture to nature is inherently anthropocentric and imposes a nature–culture dichotomy in its rationale for the nature experience. As seen from within the nature–culture dichotomy, the very term friluftsliv (free-air life) is a techne that mediates a romantic notion of nature and (re)affirms the nature–culture dichotomy. The suggestion that life in nature is life in free air that is clean and has not been polluted by humans similarly implies that life within human culture stands in opposition to it when understood within the nature–culture dichotomy. The conjecture that this is an anthropocentric relationship with nature is further supported by the one-sidedness of the informants’ relationships with nature. They all discuss what they obtain from their relationship with nature, but have little, or nothing at all, to say about how they are accountable in their relationship with nature. By arguing for a relationship with nature from an anthropocentric stance, the dichotomy between nature and culture is (re)formed (Braidotti, 2013, pp. 84–85). As such, it becomes a logical loop that enforces the dichotomy by contrasting the natural and cultural sides of the students’ beings. A more holistic, ecocentric relationship with nature cannot be found through friluftsliv if it is based on and imposes a nature–culture dichotomy. The nature–culture dichotomy creates a barrier to facilitating an ecocentric shift in the relationship between humans and nature. As the informants’ relationship with nature is manifested through friluftsliv within a nature-culture dichotomy, they are not held accountable in all aspects of their lives.

One informant, Gry, addresses the dichotomy between nature and culture in her life and tries to break the tension between human cultural life and friluftsliv life.

Gry: I now want to tear down the barrier between everyday life and friluftsliv. Some elements [of each] must be in both. So you do not put on a friluftsliv uniform and change to another, different state of being.

Instead of accepting the dichotomy, Gry actively tries to include positive elements of her friluftsliv in her everyday life and thus bridge the gap between life in nature and life in culture. Living closer to nature and attempting to bridge the gap in herself between nature and culture are among the choices Gry has made to resolve the tensions in the nature–culture dichotomy. Gry’s friluftsliv and her relationship with nature are multifaceted, as is true of all the informants. However, when she addresses the nature–culture dichotomy, she shows an understanding of the relationship between humans and nature as intra-active. Braidotti (2013, p. 191) argues that only by embracing the multiplicity of our being can we become accountable for our actions towards nature. By embracing nature and culture as intra-active ecologies, Gry has made herself accountable for her actions in both nature and culture. However, by upholding the nature–culture dichotomy in order to rationalise and define friluftsliv, the other informants do not seem to consider themselves as accountable and responsible in respect of the impact of their friluftsliv on nature. Maintaining the dichotomy may serve to justify a lack of accountability for their actions while they engage with the cultural world. This lack of accountability builds up the second tension: sustainability in friluftsliv.

Tension of sustainability in friluftsliv

The second common tension in the informants’ relationship with nature concerns sustainability in their friluftsliv and in society’s relationship with nature. Many of the informants value ecologically conscious friluftsliv and attempt to lessen their environmental impact by using public, or less, transport and second-hand, or less, clothing and gear. The informants build on the nature–culture dichotomy, however, in that they feel consciously connected with nature when they put on their “friluftsliv uniform”. However, as the personal friluftsliv of most of the informants is multifaceted, many of them also experience the conflict between the values of ecologically conscious friluftsliv and those of modern friluftsliv, as found in the sustainability paradox in friluftsliv. For example, several of the informants elaborated upon their conflicting values regarding the equipment required for modern, specialised friluftsliv and travel abroad. Frode exemplifies this conflict when he justifies the use of specialised equipment for his modern friluftsliv:

Frode: So, this is a slightly more modern version of friluftsliv that, sadly, requires a lot of equipment, so that is a slight loss, but something that gives me great joy.

Interviewer: So, it is pragmatic, and you make a compromise with yourself?

Frode: Yes. So, I must try to find a balance between nature conservation and nature enjoyment. I think that being a role model for others has to do with finding a sustainable middle way, not a way that is so extreme that everyone feels that it is too brutal, but trying to be moderate and do it in a way that still works.

Frode exemplifies how many of the informants justify themselves and make compromises in order to cope with the tension of the sustainability paradox in their friluftsliv. Several informants told similar stories, justifying friluftsliv with a larger environmental footprint while identifying with ecologically conscious friluftsliv. The students show awareness of the environmental footprint in their friluftsliv while justifying it with their positive personal outcomes and by balancing it with ecologically good deeds that tip the scales for the informants in their ethical struggle.

The informants also make strong affective statements and use apocalyptical tropes when discussing the negative impact of modern society on nature. Many informants expressed a sense of humankind’s failing custodianship of nature. There is frustration in the informants’ views on society’s relationship with nature. This problematisation of the relationship between humans and nature creates tension in the celebratory, romantic notion of nature in the students’ friluftsliv.

Hilde expresses a desire to take care of nature, but, like many of the informants, she expresses frustration over society’s anthropocentric relationship with nature.

Hilde: I want to take care of [nature], and one can see how humans affect nature negatively, with pollution and such things.

Several of the informants attempt to resolve the tension by participating in beach and town clean-ups. But, beyond that, the informants exert little influence on the relationship between humans and nature in broader society. Trying to change environmental policies can feel overwhelming, as Aall et al. (2011) discuss, and the informants expressed an inability to influence society’s relationship with nature. As the informants cope with the tensions of sustainability in society and their friluftsliv, it is apparent that they have a very private relationship with nature. Few of them have openly discussed their values and their relationship with nature in their friluftsliv with friends or fellow students. Instead, the students talked about by being good role models so as to influence others to become more environmentally conscious in their friluftsliv.

As seen above, Gry strove to rethink the nature–culture dichotomy in her life. Braidotti (2013, p. 49) shows that realising that one is oneself embedded in an array of non-exclusive belongings allows for accountability. By consciously choosing to address the dichotomy between nature and culture in her life, Gry has become accountable for the state of the relationship between humans and nature in society. Gry is the only informant who discussed actively lobbying for change in society through environmental activism. When the relationship with nature is defined by the human visitor who returns to the cultural world by taking off their “friluftsliv uniform”, there can be no accountability for the relationship between humans and nature. Only by acknowledging that nature and culture are two sides of the same ecological coin can we move past the anthropocentric exploitation of nature and towards a sustainable relationship between humans and nature (Ferrando, 2016).

Implications for friluftsliv and outdoor education

Ecocriticism and posthumanism have provided a novel framework for critically investigating friluftsliv students’ relationships with nature. I have argued that the informants in this study mediate their relationship with nature through a techne of the nature–culture dichotomy that fosters unaccountability. This study contributes new insight that may be valuable in designing friluftsliv and outdoor education praxis that addresses education for sustainable development.

In order to have a sustainable relationship with nature, we need to move away from an anthropocentric, dichotomic relationship towards an ecocentric, embedded, and entangled relationship in line with posthuman ontology (Braidotti, 2013; Ferrando, 2016). As posthuman ontology suggests, we should see nature and culture not as separate but as intra-active ecologies along a nature–culture continuum of environments. Only by being non-exclusively embedded in and embodied by nature and culture can we hope to take responsibility and be accountable for our relationships with the environment. I believe, as is argued in environmental and ecological philosophy, that the personal experience of nature is vital in this shift towards a responsible and accountable relationship with nature (Næss, 1999; Vetlesen, 2015). Friluftsliv and outdoor education have the potential to facilitate such a change.

Based on this study and the theoretical framework of posthuman ecocriticism, outdoor educators who hope to contribute to sustainable development must critically examine their relationship with nature. Educators should hold themselves and their students accountable and take responsibility in their relationships with nature. To facilitate sustainable relationships with nature that are characterised by accountability, I would argue that outdoor educators must mediate nature experiences using a techne of the nature–culture continuum rather than a dichotomy. Furthermore, the language used when talking about nature and experiences in nature is powerful and should be scrutinised for how it conveys the relationship with nature. Consequently, I call on outdoor educators to make explicit their personal and institutional relationships with nature and how these relationships are characterised in educational praxis.

What it means to use the techne of a nature–culture continuum to mediate nature in friluftsliv and outdoor education is not clear to me at this point. To paraphrase Braidotti, (2013, p. 82), the collapse of the nature–culture divide requires that we devise a new vocabulary, with new tropes to refer to the relationship between humans and nature in sustainable friluftsliv and outdoor education. In other words, this is a process that will take time and critical thinking within educational praxis. I believe, however, that such effort will be worthwhile, as a relationship between humans and nature that is built on a nature–culture dichotomy is not, and never has been, sustainable.

Further research is needed on the conceptual and practical implications of the ecocritical and posthuman understanding of the relationship between humans and nature in friluftsliv and outdoor education. In addition, other critical approaches to the relationship between humans and nature in friluftsliv and outdoor education may provide additional insight into educating for sustainability in these educational programmes.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the friluftsliv students for participating in this study and for taking the to give me detailed accounts of their relationships with nature. I would also like to thank the two anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive feedback on the manuscript. Lastly, I must thank professor Nina Goga for her valuable guidance as I grappled with the posthuman and ecocritical perspectives on the relationship between humans and nature.

Litteraturhenvisninger

Backman, E. (2011). Friluftsliv: a contribution to equity and democracy in Swedish Physical Education? An analysis of codes in Swedish Physical Education curricula. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(2), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2010.500680

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

Beery, T. (2014). People in nature: Relational discourse for outdoor educators. Research in Outdoor Education, 12, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1353/roe.2014.0001

Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Polity Press.

Braidotti, R. (2019). Posthuman knowledge. Polity Press.

Breivik, G. (2020). ‘Richness in ends, simpleness in means!’ on Arne Naess’s version of deep ecological friluftsliv and its implications for outdoor activities. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2020.1789719

Chawla, L. (2006). Learning to love the natural world enough to protect it. Barn, 2, 57–78.

Ferrando, F. (2016). The party of the anthropocene: Post-humanism, environmentalism and the post-anthropocentric paradigm shift. Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism, 4(2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.7358/rela-2016-002-ferr

Faarlund, N. (2020, 27 March). Karriere fremfor naturvennlighet? [Career rather than nature friendliness?]. UTE, p. 96.

Garrard, G. (2012). Ecocriticism (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Gelter, H. (2010). Friluftsliv as slow and peak experiences in the transmodern society. Norwegian Journal of Friluftsliv. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-9185

Goga, N. (2016). Miljøbevissthet og språkbevissthet. Om ungdomsskoleelevers møte med klimalitteratur [Environmental awareness and language awareness. About middle school students’ encounter with climate literature]. Norsklæreren, 3, 60–72. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d00b418d9cad80001fc3882/t/5d68e01ab3cf300001b170dc/1567154209213/NL3-16_Goga.pdf

Goga, N., Guanio-Uluru, L., Hallås, B. O., & Nyrnes, A. (2018). Introduction. In N. Goga, L. Guanio-Uluru, B. O. Hallås, & A. Nyrnes (Eds.), Ecocritical perspectives on children’s texts and cultures: Nordic dialogues (pp. 1–23). Springer International Publishing.

Gruas, L., Perrin-Malterre, C., & Loison, A. (2020). Aware or not aware? A literature review reveals the death of evidence on recreationists awareness of wildlife disturbance. Wildlife Biology, 2020, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2981/wlb.00713

Gurholt, K. P. (2008). Norwegian friluftsliv and ideals of becoming an ‘educated man’. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 8(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670802097619

Gurholt, K. P., & Haukeland, P. I. (2019). Scandinavian friluftsliv (outdoor life) and the Nordic model: Passions and paradoxes. In M. Tin, J. O. Tangen, F. Telseth, & R. Giulianotti (Eds.), The Nordic model and physical culture (pp. 165–181). Routledge.

Hallås, B. O., Aadland, E. K., & Lund, T. (2019). Oppfatninger av natur i planverkene for kroppsøving og mat og helse i femårige grunnskolelærerutdanninger [Nature representations of nature in curriculum for physical education and food and health in five-year teacher education]. Acta Didactica Norge, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.6097

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860220137345

Haukeland, P. I., & Sæterhaug, S. (2020). Crafting nature, crafting self: An ecophilosophy of friluftsliv, craftmaking and sustainability. Techne serien – Forskning i Slöjdpedagogik och Slöjdvetenskap, 27(2), 49–63. https://journals.oslomet.no/index.php/techneA/article/view/3695

Hille, J., Aall, C., & Klepp, I. G. (2007). Miljøbelastninger fra norsk fritidsforbruk – en kartlegging [Environmental impacts from Norwegian leisure consumption – a survey] (VF report, issue 1/07). https://www.vestforsk.no/sites/default/files/migrate_files/rapport-1-07-fritidsbruk.pdf

Høyem, J. (2020). Outdoor recreation and environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 31, 100317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100317

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2021). Summary for policymakers. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. C. U. Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/#SPM

Kloet, M. A. V. (2010). Cataloguing wilderness: Whiteness, masculinity and responsible citizenship in Canadian outdoor recreation texts [PhD thesis, University of Toronto]. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=NR79366&op=pdf&app=Library&oclc_number=1019467830

Leirhaug, P. E., Haukeland, P. I., & Faarlund, N. (2019). Friluftslivsvegledning som verdidannende læring i møte med fri natur [Friluftsliv as value, Bildung and learning in meetings with free nature]. In L. Hallandvik & J. Høyem (Eds.), Friluftslivspedagogikk (pp. 15–32). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Lo Iacono, V., Symonds, P., & Brown, D. H. K. (2016). Skype as a tool for qualitative research interviews. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3952

Loynes, C. (2018). Theorising outdoor education: Purpose and practice. In T. Jeffs & J. Ord (Eds.), Rethinking outdoor experiential and informal education (pp. 25–39). Routledge.

Lumber, R., Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. (2017). Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLOS ONE, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177186

Martin, P. (1996). New perspectives of self, nature and others. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 1(3), 3–9.

Meld. St. 18 (2015–2016). Friluftsliv. Natur som klide til helse og livskvalitet [White paper on friluftsliv and nature as a source for health and quality of life]. Klima- og miljødepatementet. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/9147361515a74ec8822c8dac5f43a95a/no/pdfs/stm201520160018000dddpdfs.pdf

Mikaels, J. (2017). Becoming-place: (Re)conceptualising friluftsliv in the Swedish physical education and health curriculum [The Swedish School of Sports and Health Sciences]. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1144172/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Næss, A. (1999). Økologi, samfunn og livsstil [Ecology, community and lifestyle] (5th ed.). Bokklubben dagens bøker. https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digibok_2008090301002

Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Pleasants, K., & Stewart, A. (2020). Entangled philosophical and methodological dimensions of research in outdoor studies? Living with(in) messy theorisation. In B. Humberstone & H. Prince (Eds.), Research methods in outdoor studies (pp. 9–20). Routledge.

QSR International Ply Ltd. (2020). NVivo (12th ed.). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

Straume, I. S. (2020). What may we hope for? Education in times of climate change. Constellations, 27(3), 540–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12445

UNECE. (n.d.). EDS Strategy. https://unece.org/esd-strategy

Vetlesen, A. J. (2015). The denial of nature: Environmental philosophy in the era of global capitalism. Routledge.

Aall, C., Klepp, I. G., Engeset, A. B., Skuland, S. E., & Støa, E. (2011). Leisure and sustainable development in Norway: Part of the solution and the problem. Leisure Studies, 30(4), 453–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.589863