Med mål om å bryte nytt land for et mer demokratisk skolesystem

Vår tid, som kan defineres gjennom den globale kampen for å bevare planeten, det nylige møtet med den livstruende covid-19-pandemien og en økning i antall autokratier, har tydelig vist at demokrati og internasjonal diplomatisk kommunikasjon er avgjørende.

Nødvendigheten av å bygge demokratisk kompetanse i møte med dagens globale utfordringer strømmer ned i læreplanene. Som en illustrasjon på dette innførte Norge i 2020 en ny læreplan som formidlet en forventning om at elevene skulle oppleve et demokratisk skolesamfunn i praksis. Som svar på den nye læreplanen besluttet en videregående skole i Norge i 2019 å begynne arbeidet med å utvikle og implementere en ny pedagogisk modell. Ambisjonen var å øke elevenes følelse av medbestemmelse og deltakelse i skolen, lokalsamfunnet og samfunnet for øvrig. Deretter har en tverrfaglig pedagogisk modell vært under utvikling ved skolen, der faginnholdet er organisert etter overordnede tema. Disse emnene presenteres for elevene som læringsoppdrag.

Gjennom dybdeintervjuer med lærere og ledere som jobber med å utvikle den nye pedagogiske metoden, undersøker denne artikkelen hvilke utfordringer og muligheter deltakerne møtte i denne prosessen. Dataene er kodet gjennom en trinnvis deduktiv-induksjonsmetode og analysert ved hjelp av Bernsteins konsepter for klassifisering og ramme. Deltakerne identifiserte skolens lite fleksible organisasjonsstrukturer – som skoleadministrativt system, bygningen, vurderinger og den fastsatte timeplanen – som aspekter som gjorde det utfordrende for skolen å gå bort fra den formidlingsbaserte tilnærmingen til utdanning. Omvendt er implementering av tverrfaglige temaer i norsk læreplan ett eksempel på en strukturendring som deltakerne mente hadde åpnet for mer fleksibilitet. Deltakerne opplevde imidlertid at denne fleksibiliteten ikke ble utvidet inn i regelverket som styrer tidsbruken på skolen eller vurderingsskjemaene. Derfor konkluderer artikkelen med at strukturelle endringer er nødvendige for å muliggjøre framveksten av pedagogiske modeller som kan øke elevenes medbestemmelse, aktive deltakelse og virkelighetsnære erfaringer i skolen.

On a Mission to Break Ground for a More Democratic School System

Our current era, which can be defined by the global struggle to preserve the planet, the recent encounter with the life-threatening COVID-19 pandemic, and a rise in the number of autocracies, has clearly shown that democracy and international diplomatic communication are crucial.

The importance of building democratic competency in the face of current global challenges cascades down into national curricula. Illustratively, in 2020, Norway introduced a new national curriculum that conveyed an expectation that students should experience a democratic school society in practice. In response to this new curriculum, in 2019, an upper secondary school in Norway decided to embark on a mission to develop and implement a new pedagogical model. The ambition was to increase the students’ sense of codetermination and participation in school, the local community, and society at large. Subsequently, an interdisciplinary pedagogical model has been in development at the school, in which the subject content is organized according to overarching topics. These topics are presented to students as quests called learning missions.

Through in-depth interviews with teachers and leaders currently working on developing the new pedagogical method at the school, the current article investigates the challenges and opportunities the participants encountered in this process. The data have been coded through a stepwise deductive-induction method and analyzed using Bernstein’s concepts of classification and frame. The participants identified the inflexible organizational structures of the school—such as the school administrative system, the building, assessments, and the set timetable—as aspects that made it challenging for the school to depart from the dissemination-based approach to education. Inversely, the implementation of interdisciplinary topics in the Norwegian National Curriculum is one example of a structural change that the participants thought had opened up more flexibility. However, the participants experienced that this flexibility was not extended into the regulations controlling how time is spent in school or the assessment forms. Hence the article concludes that structural changes are necessary to enable the growth of pedagogical models that can increase students’ codetermination, active participation, and real-life experiences in schools.

Introduction

Our current era, which can be defined by the global struggle to preserve the planet, the recent encounter with the life-threatening COVID-19 pandemic, and a rise in the number of autocracies, has clearly shown that democracy and international diplomatic communication are crucial. Concerningly, the 2021 V-Dem Institute’s Democracy Report shows that, over the past two decades, the global level of democracy has declined to its 1989 level (Boese et al., 2022). Similarly, according to the Global Democracy Index, the year 2021 marked another major decline in the global level of democracy (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022). Within the international community, there has been broad agreement that education is essential for turning this trend around. When young students are allowed to be active agents in their community and voice their opinions through education, this increases their level of civic engagement (OECD, 2022). Correspondingly, the importance of building democratic competency in the face of global challenges cascades down into national curricula and school policy.

Illustratively, in 2020, Norway introduced a new national curriculum expressing the expectation that students should experience a democratic school society in practice, stating, When the voices of the pupils are heard in school, they will experience how they can make their own considered” (Ministry of Education and Research, 2017, 2.5) The curriculum includes a core curriculum, published already in 2017 and implemented in 2020, that provides values and principles for Norwegian education, for example, by calling for more active participation and codetermination for students, not only in the school’s student council but also in everyday school life and practice. Furthermore, the core curriculum introduced three interdisciplinary topics: 1) health and life skills, 2) democracy and citizenship, and 3) sustainable development. This is the first time in Norwegian school history that the national curriculum includes three named interdisciplinary topics that are mentioned in the introduction of every subject curriculum and explicitly tie together various competency goals from the individual subject curricula with the expressed intent of making the students see the connections between subjects (Ministry of Education and Research, 2017).

In response to the new curriculum, in 2019, an upper secondary school in Norway decided to embark on a mission to develop and implement a new pedagogical model. The ambition was to increase the students’ sense of codetermination and participation in school, the local community, and society at large. Another major aspiration was to facilitate holistic, personalized, student-engaging, relevant, and social in-depth learning through structural reorganization. There were approximately 1,800 students at the school, and many of these students were attending a vocational education program. An interdisciplinary pedagogical model was put into development at the school, in which competency goals were organized according to overarching topics. These topics were presented to the students as quests—called learning missions—through which the ambition was that the students would be invigorated to explore relevant content and choose appropriate learning methods themselves. The new learning mission model was implemented incrementally starting in September 2020, following the implementation of the new National Curriculum (LK20).

The research in the current article is based on in-depth interviews with teachers and leaders who were working to develop the new pedagogical method at the aforementioned upper secondary school. All the participants were key players in the development work at the school and represented a development work undertaken from 2019 until the writing of this article, which affected approximately 750 students in its first year and approximately 1,500 students annually after 2021. The research was part of a larger Action Research Public Sector PhD project, which entailed me being both a teacher and a researcher at the upper secondary school. The study was financed by the school owner and the Research Council of Norway.

The research question addressed in this article is:

What are the challenges and opportunities the teachers and leaders have encountered in the process of transitioning to learning missions?

This is an important question to explore because the school’s development work is a micro-level example echoing a macro-level ambition in international educational policy. The ambition behind the school’s development project was to move toward a more interdisciplinary, active, and student-centered approach. influential policy reports, such as the OECD report Schools for 21st Century Learners and the Horizon Report 2015 (Johnson et al., 2015; Schleicher, 2015).

Generally, research has supported the idea that transitioning to more student-active methods is advantageous. Active learning is defined as “learning that requires students to engage cognitively and meaningfully with the materials” (Chi & Wylie, 2014, p. 219) and is often contrasted with dissemination-based learning. In a one-way lecture, for example, the teacher facilitates a passive mode of engagement centered around the teacher´s activity and expects the students to ensure that the material is processed. In the active learning approach, both the learners and the teacher(s) are predominantly attentive to how the material is processed by the students, and the teachers aim to facilitate situations in which the learners are allowed to engage with the material. (Bonwell & Eison, 1991; Chi & Wylie, 2014; Deslauriers et al., 2019; Prince, 2004). Fullan et al. (2018) have shown that deep learning and the transition to active learning are intrinsically linked. Other studies have found that combining elements from project-based learning and problem-based learning can enhance critical thinking and student engagement (Hanney & Savin-Baden, 2013; Shekhar et al., 2020). Moreover, a meta-study from 2019 that compared and analyzed the findings from 299 studies concerning the impact of student-centered instruction methods, concluded that a more student-centered approach can lead to significantly better learning achievement for students than the traditional dissemination-based approach. In the implications for further research, Bernard et.al argued that research should move beyond comparing whether new practice outperforms traditional classrooms to the questions of how nontraditional approaches can be further developed (Bernard et al., 2019). It is in this context that it is interesting to explore what hinders and enables the development of a more student-active, interdisciplinary approach in a school that has centered on such a transition.

Because the Norwegian National Curriculum, LK20, is new and has been implemented amid COVID-19 measures, there has been limited research on the renewed curriculum’s consequences for practice. The research project Evaluation of the Subject Renewal (EVA) published two reports on the process leading up to the implementation of the new curriculum. In their first report, they argued that the introduction of interdisciplinary topics might lead to confusion and tension because it is unclear how and to what degree the various subjects should be integrated into the practical work with the interdisciplinary topics (Karseth et al., 2020). This confusion was echoed by Andreassen and Tiller (2021) in their extensive analysis of the LK20 curriculum, who even questioned whether the Core Curriculum’s interdisciplinary topics were merely intended as a guide for the authors of the specific competency goals and not for the teachers working with the curriculum (2021, p. 227). The EVA’s second report explored the tensions revealed in the practical preparation for implementing the curriculum. The authors critically questioned how the tension between implementing something new while simultaneously building on existing practice can affect and limit the new practice (Ottesen et al., 2021, pp. 83–89). The current article’s data material has suggested some answers to the questions posed in EVA’s reports: the challenges and opportunities the participants have encountered while implementing a pedagogical model that responds to the ambitions of LK20 can elucidate the effect of such structural tensions, particularly those related to interdisciplinary topics and active learning.

A literature review of Norwegian research on civic and citizenship education from year 2000 and onward has indicated that even though teachers know that it is important that educators and schools should strive to develop active democratic citizens, it is often unclear to the practitioners how this should be done in practice (Biseth et al., 2021). That there exists a general plurality in the understanding of democracy which affects what practice looks like has been systematically studied in an international, theoretical review of 377 peer-reviewed articles examining how democratic education is conceptualized. Sant showed how different normative understandings of democracy have impactful implications for practice (Sant, 2019). Given that it is an explicit goal in the Norwegian Core Curriculum to enable students to act as active democratic citizens in their current school situation, the curriculum instructs Norwegian practitioners that students should learn to be democratic citizens through democracy, not only for democracy in their future as adults. Research has illuminated that to enable active participation, it is necessary for schools and their practitioners to have a broader focus than only strengthening civic knowledge. Skills, experiences, attitudes, values, and belief in future participation can be supported by focusing on developing the students’ sense of political efficacy, by creating an open classroom climate, and by active participation and experiential learning (Blaskó et al., 2019; Hoskins et al., 2015; Kosberg & Grevle, 2022; Ødegård & Svagård, 2018; Sohl & Arensmeier, 2015; Westheimer, 2015). Although several studies have discussed the teachers’ understanding of democracy or pedagogy, the current research study has elucidated which aspects of school life practitioners, who already conscientiously work toward the ambition to strengthen students’ opportunity to be active participants in their own everyday school life, identify as challenges and opportunities. This contribution can provide valuable insights into the measures that can be undertaken in research and at the policy level to support practitioners.

Theory

Bernstein’s (1973) concepts of classification and frame, which are related to identifying the educational knowledge code—the founding principles that guide curriculum, pedagogy, and evaluation—were helpful to relate the micro-level experiences in the empirical data at a macro theoretical level. By analyzing the data through Bernstein’s concepts, I was able to cluster the complexity of the data, which allowed me to present the data more coherently and concisely.

“curriculum defines what counts as valid knowledge, pedagogy defines what counts as a valid transmission of knowledge, and evaluation defines what counts as a valid realization of this knowledge on the part of the taught” (1973, p. 47). He sorted curricula into two categories based on their level of classification, that is, the level of the boundary between content: 1) the collection type is curricula with closed relationships between content, and 2) the integrated type refers to curricula with weak boundaries between content. In a collection type, the boundaries between content are what shape identity and one is socialized into the codes of a particular discipline. Interdisciplinary topics would be an example of a more integrated type, as the boundaries between content are weaker.

Framing, on the other hand, refers to the degree of control the teacher and learners have over what is transmitted at the pedagogical level. If the framing is strong, there are limited options for the teacher, even though the teacher is powerful in relation to the student and the student cannot affect what, how, or where the content is taught. When framing is weak, however, the student’s prior knowledge is welcomed, and there is little insulation separating the student’s world outside of school from that in school.

If both classification and framing are strong, the educational relationship is shaped by traditions and the pupil is seen as ignorant with little power (Bernstein, 1973, p. 51). In other words, if one is to follow the logical line of Bernstein, to increase the students’ level of opportunity to partake in decision-making in everyday school life, it is necessary to move in a direction toward weak classification and framing. As mentioned in the introduction, it is an explicit ambition in the Norwegian Core Curriculum to increase the students’ opportunities to participate actively and partake in decisions regarding everyday life in school and class.

However, weak classification and framing entail blurring the lines between what is and is not considered knowledge, which, according to Bernstein, will most likely direct attention toward how knowledge is built rather than which knowledge should be attained. Furthermore, more of the student’s life in terms of feelings, values, and context is exposed in the educational setting, which may result in a more intense and thorough socialization process. A sudden change in the cultural traditions of classification and framing leads to resistance. This is why a transition to a weaker classification and framing presupposes solidarity and a shared understanding among the employees that such a transition entails a different learning output, whereas the lack of such support can lead to a problem of order within the organization (Bernstein, 1973, pp. 63–66).

Andreassen (2016) used Bernstein’s theoretical framework when analyzing the room for action where the various competency goals extend to the schools, the teachers, and the students in the Norwegian Curriculum from 2006 (LK06). Additionally, he explored the same categories when analyzing the National Curriculum of 2020 together with Tiller (Andreassen, 2016; Andreassen & Tiller, 2021). The current study further explores this room for action from the practitioner's perspective and shows that not only do the competency goals affect the classification and framing for the participants, but from their perspective in the practice field, in which all aspects that influence school life are merged into practice, they also highlight how other aspects of school, such as the school administrative system or the building, affect the level of classification and framing. This is important because it suggests that such aspects should receive more attention.

Fullan had a similar understanding to Bernstein, making a distinction between deep learning and the traditional grammar of school. According to him, traditional grammar is a “conservative default culture that provides a sense of security, familiarity, and predictability. The default culture, as if it had a life of its own, seems ready to neutralize or blunt any serious attempt at change” (Fullan, 2020, p. 654). Also, it is necessary to break out of this grammar to enhance the quality of learning and achieve deep learning (Fullan et al., 2018).

Methods

The data presented in this article are based on 1) unstructured individual interviews, and 2) unstructured group interviews. In the individual interviews, open-ended questions were posed directly to the participant by me. In the group interviews, the participants were seated around a table and given Post-it notes. Each participant had a specific color Post-it note. On the table, there were two A3 pieces of paper, one labeled “challenges” and one labeled “opportunities.” Two of the groups were also given a third poster, labeled “wishes,” because they presented a few notes that could be more accurately described as wishes. Throughout the group interviews, the participants wrote down the challenges and opportunities they had experienced while transitioning to teaching through learning missions and sorted them into the two, sometimes three, categories. Throughout the interviews, the participants wrote short notes, sorted them into the most appropriate category, explained and discussed what they meant by what they had written on the notes, and talked about their experiences linked to the content. The participants also exchanged experiences and discussed similarities and differences of their experiences.

I developed the method in this way because I wanted the interview to take the form of an informal conversation. As this study is part of an action research study and as I am also a practitioner at the school and a colleague to the participants, I intended this study to both enable fruitful exchange between the participants in the ongoing action and document the findings of the unstructured interviews. This turned out to be advantageous because the conversation brought up aspects that were relevant to the practitioners. After the interviews, several of the practitioners expressed that they thought it had been useful to participate in the interviews and that they enjoyed the way I had set it up because it was easier for them to shape the interview so that it brought up what was relevant for them. Swain and King (2022) argue in an article on informal conversations in qualitative research that this approach might create more ease of communication and therefore be advantageous for the quality of the conversation. They distinguish informal conversations from unstructured interviews, as the latter is planned. (Swain & King, 2022). In the current study I have, therefore, unstructured interviews and incorporated elements from informal conversations.

Participant selection consisted of 13 employees at the school. Most of the participants hold at least two of the following roles: leader, teacher specialist, or teacher. The school offers a range of educational programs, and the participants mirrored the diversity of these different programs. Consequently, both teachers and subject teachers were represented. The informants were invited to the interviews and selected because of their active participation in developing and evaluating the learning missions. The current study was part of a larger public sector doctoral dissertation work, meaning that I was both a teacher and researcher at the school. This double role gave me valuable insights into whom I should invite to participate in the interviews. All the quotes have been translated from Norwegian into English by me.

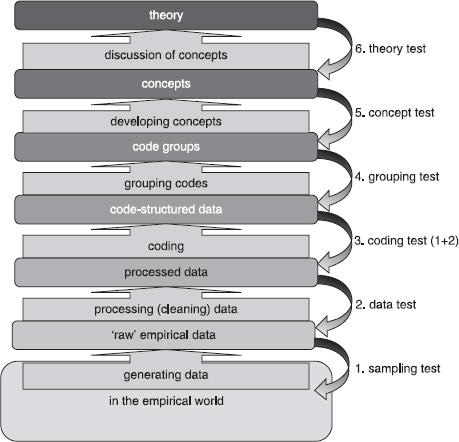

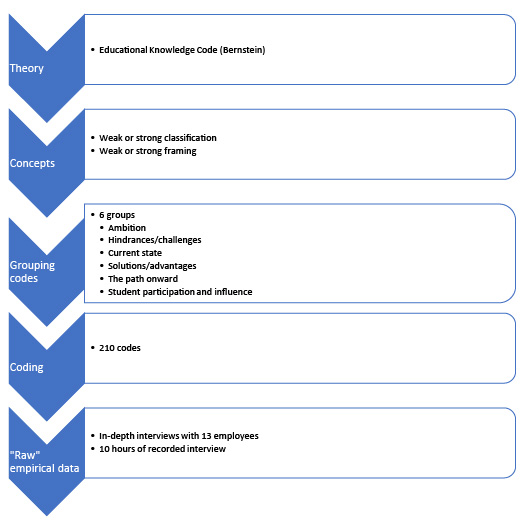

All the interviews lasted for one to two hours and were video recorded. The recordings and the Post-it notes were transcribed and then coded in two rounds. The program NVivo was used to transcribe and code the data. I based the coding approach on Tjora’s (2019) stepwise deductive-induction method of coding, which is illustrated in Figure 1.

Source: Tjora, 2019, p. 3

In the first round of coding, I coded the content using an inductive descriptive approach, during which I ended up with approximately 210 codes. In the second round, I thematically sorted the codes and identified six code groups. This stage made me understand that Bernstein´s concepts of classification and framing from the theory of the Educational Knowledge Code were appropriate to reduce the complexity of the data material in the analysis.

Adapted from Tjora (2019).

Findings

The presentation of the findings is divided into four sections: In the first section, I elucidate how the participants explained the ambition for the new pedagogical model. Even though I knew the ambition at the school well, both as a teacher and researcher, it is important to shed light on how the participants conceptualized this vision. In the second section, I summarize the most common challenges the participants encountered. The third section describes how the participants framed the difference between the ambition and reality of the new pedagogical approach. In the fourth and final section, I summarize which solutions and advantages the participants encountered after they had transitioned to working with learning missions.

Most of the participants viewed the new ambition as a conscious breakage with many aspects of the traditional way of teaching. One participant, for example, described that the set-up of a traditional classroom was not ideal for learning: “The best learning does not happen sitting at desks; this has been a very important premise … it is an important part of it that learning should happen other places than only within the school.” Similarly, several participants explained that the set timetable was perceived as a traditional aspect of school that did not fit well with the new pedagogical ambition:

The way it was intended was that the timetable would be dissolved, and then, the Norwegian teachers, the English teachers, and the program subject teacher would sit there as a resource for the students, who would be able to approach them to seek knowledge and get help …

Moreover, the traditional dissemination-based approach to teaching was seen as not fulfilling the criteria for the learning missions, as described by one of the leaders at the school:

We made a template that the teachers should plan their teaching against. It was also a kind of reminder list … if you checked the “low” box on everything, such as student activity, there is no teaser, nothing that triggers motivation … in a way, it is a PowerPoint and an assignment afterwards; then, you should think whether to adjust your plan. That was the idea.

One participant explained why the dissemination-based approach was discouraged: “To fill up, memorize, and spit it out afterwards, that is the opposite of student-active learning, I think…”.

A challenge brought forward by the participants was how a new administrative computer system, which was also introduced to the employees in 2020 along with the new curriculum, had further illuminated to the participants the complexity of the organizational structure in an upper secondary school. The system counts the appropriate number of hours per subject, student and teacher so that it will fit perfectly with the regulations. One leader described this shift as follows:

The dream was that the school would flow just a bit more; we then got a school administrative system parallel with this, which, if possible, was even more rigid than the former system we had, in which an entire year had to be planned before the summer at a detailed level. We have to insert whether we are going to have an alternative activity because that is not counted on the teacher and it is not counted in the subject.

Ironically, the improved software enhanced the possibility of monitoring the complex regulations of upper secondary education perfectly, and this shift made the school´s organizational structure seem more fixed. One leader explained how detail-oriented the computer system allowed the school to be:

This is why we have a 48-minute model here, to have five days during the year that can be used on some other activities than just the pure timetable, so that means that … if we would have had a 45-minute model, we could not have had any activities at all; we could not have had the team spirit day; we could not have had the sports day. Then, we could not have had any theme day, we could not have had the mock exams, and we could not have had any of those things, which is why we have set up a bit longer sessions … it influences that much those three minutes. It sounds ridiculous, but it is very bureaucratic I think; it is all about counting and such, that is, the technology we have as a school administrative system.

One participant reflected on why the system has been set up in this way:

Technology makes it more difficult because it is bureaucratic technology … the transition that we have had to … the school administrative system, it is entirely correct everything in there, the number of hours, everything is following the regulations, but it is not necessarily in accordance with what is communicated about thinking interdisciplinary and doing what was expected from the White Papers from the Parliament leading up the renewal of the curriculum because there was a lot of focus on flexibility, I felt, and a focus on finding solutions, thinking interdisciplinary and such, which our school technology is not built for at all.

This impression of the school administrative computer system as a hindrance to more flexibility in school was also echoed in teachers’ descriptions. Several considered the system to hinder pedagogical development, as exemplified below:

Participant A: There is (anonymized name of school administrative system) which is so locked that it … destroys everything!

Researcher: How so?

Participant A: The leaders are obliged to insert all hours in the system and have them counted, and the system is so rigid that it is not possible to move hours or dissolve timetables or the equivalent because this makes the system crack.

Participant B: It is the world’s worst computer system.

When I asked the participants whether this challenge would have been solved by removing the new administrative computer system, one leader answered with the following:

No, I think maybe we had not managed it completely … with our old system either because there is something about how it is connected with absence management, it is connected with a lot, but with the school´s administrative system, it is almost connected with the salary of the individual teacher, in addition, meaning that the lesson must be held. But it is difficult to get some flexibility when the schedule is as tight as it is here.

This shows how the complexity of the various national regulations for compulsory instruction time in the classroom, such as students’ absence management and teachers’ employment contract, constitute the core of the challenge that the participants encountered, and not the administrative computer system itself.

One leader expressed resignation when describing how timetables and the complex structure in school made it difficult to break out of the traditional pattern when working with the interdisciplinary learning missions:

A learning mission could have been much better if one would have had more flexibility... I think that ... it forces us into old thoughts about yes, then, I will make a lecture plan for the subject Norwegian, and then, you will make a lecture plan for ehm … simply put, timetables and structures in school are a hindrance for working more flexibly, so it becomes … at the same time, it is about those agreements we are tied to … that is just the way it is. So then, we make the best out of the situation and the framework we have.

Another common challenge discussed was related to the school’s building and facilities, which were designed for a traditional and dissemination-based model. The school was expecting funding to build a new school, but when three counties were merged into one in January 2020, these plans changed. At this point, the school had already started the process, as described by one leader:

... we planned a new school building, which was designed in such a way that things looked very different, there was much more room for sitting and working differently in a much more social way of working. For example, there were no desks and chairs in lines and rows in a room and such things, which we really liked, but it cannot be like that now, meaning that the building structure is actually a structural hindrance.

A different leader expressed the following:

I wish we had learning areas that were much more adjusted to a different way of working because now, it is very closed. There is one teacher in each classroom with one class; that is what our school is built for.

The teachers conveyed that the building structure made it difficult to be creative and give students a physical space to cooperate.

I can say that ok, in this learning mission I am not going to stand in the front and chatter, but there is no room to run the class creatively because we do not have any space other than the classroom.

When the only available space was a traditional, poorly equipped classroom, teachers felt that it was more challenging to give creative assignment in which the students would for example make products, film, record sound, role play, or have private conversations, and made sitting by their desk the easiest choice by default. One participant called this the “learning by sitting” approach of school.

A similar situation was described for the workshops at the vocational school, which, because of the lack of space, had been spread out to different locations. For some of the students and teachers, their school week was spread out to four different locations, making it problematic to create one coherent product following the ambition of the learning missions. Having the mechanical workshops and the subject teachers separated in different locations meant that the students had to learn specific techniques in isolation, such as welding, instead of being able to use the welding on a product they were working on in the other workshop The teachers thought this was a frustrating hindrance.

Some of the participants addressed how the usefulness and personal development the students experienced through the learning mission were not necessarily reflected or awarded in the assessments of the students’ acquired competency. One leader discussed this:

I think that it is very closely related: assessment and learning mission must be seen in connection because if these do not align, then you will not get anywhere. There is something that the traditional assessment type is that you go through something, and then, you get a test at the end; and that does not align with what learning missions are”… they should rather be evaluated in the process I …. It is absolutely a part of these learning missions that it shall not end up in a test at the end.

A teacher participant, however, expressed the difficulty of measuring the students´ development as a result of the learning missions through assessments in the following manner:

I experience that the students are in such good personal development, and they grow while they attend this school. I think it is very difficult to put that into a graded assessment ... I think that if we are going to take this about learning missions to its result, then we must have a different grading system or assessment system, which is much more nuanced and personally directed; we should not have just a cluster to measure everyone up against each other.

Additionally, challenges related to cooperation and time were mentioned by the participants numerous times during the interviews. This was particularly highlighted as a challenge with assessments and exams. Several participants thought the interdisciplinary learning missions created an advantageous potential for having fewer exams and formal evaluations as this could lower the students’ sense of stress, and hence increase the potential for in-depth learning. As the timetable was not set up for interdisciplinary lectures or assessments, the teachers had to find creative solutions when assessing the interdisciplinary learning mission. Several participants mentioned that it was a challenge to find the time for developing the framework for and conducting joint assessments with the various teachers involved. Some mentioned that they filmed the students while presenting their product and subsequently shared the film with the other subject teachers. Others voluntarily worked to attend a common assessment when they do not have classes, as exemplified in the following extract:

It [the assessment ] was a role play, and then, I am actually sitting there class periods that week, which I will not get paid for, so it is understandable that a teacher will react … but if it is going to work, I have to do it like that; if not, I would not have succeeded in cooperating with my colleague in those class periods. So that is a measure that I do, but I cannot expect as a colleague…that they (other colleagues) will do that for free.

In Norway, teachers are paid for the class periods for which they teach, and in addition, they have some inflexible and flexible time for preparation and development work. When the participant stated, “to work for free,” they meant that leaders/colleagues cannot require teachers to teach during their preparation- and development time, which again entails that participating in other class periods than their own becomes voluntary work which cannot be formally expected or systematized at an organizational level. Several participants expressed in the interviews that it would be a dream to have the timetable dissolved, at the very least when there were assessments for the students.

According to one leader, the new ambition created a breach among the employees at the school: “The challenge, from my perspective, has been the conflict that arose between what we can call the traditionalists and the modernists … and that conflict stopped a lot of the process, so that was tremendous work in the beginning.” Although several of the participants described that they had experienced such resistance from others, none of the participants expressed negative attitudes toward transitioning to the learning missions. This may be because all the participants had been active in developing the new model.

Several participants also mentioned that the students were not used to active learning and that the transition was a challenge:

The biggest challenge … is that the students are not used to active learning at all; they are not used to seeking out learning. They are used to sitting completely still and calm on their chair and shutting up, preferably with earplugs in the ear and hood over, so it looks like they are listening to music.

The fact that the students were not used to active learning and expressed passivity underlined the importance of shifting to a new pedagogical model for the participants who had encountered this challenge.

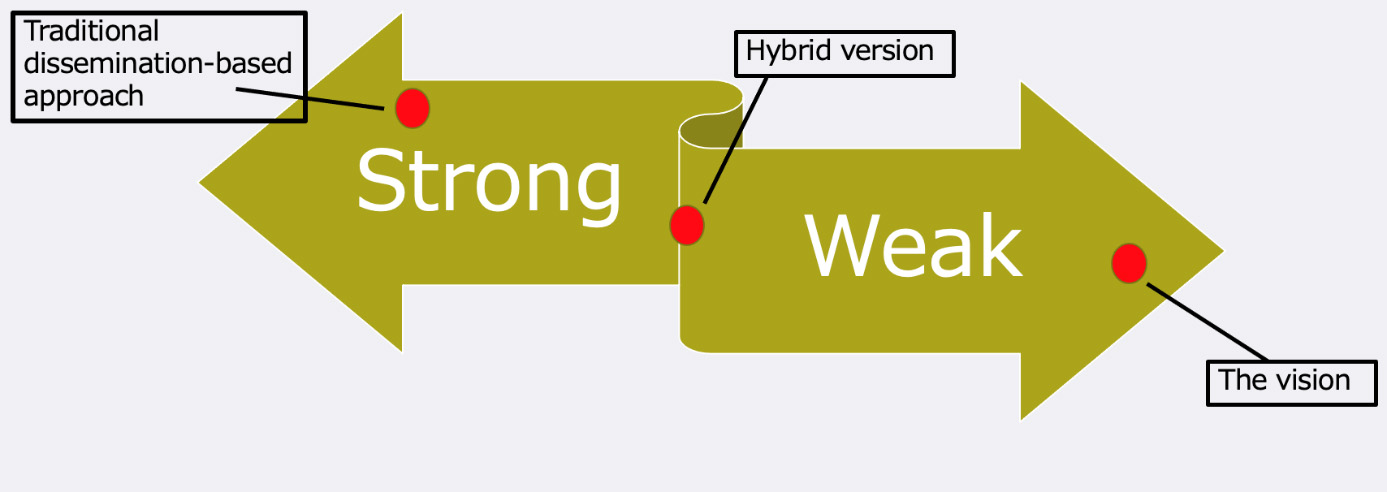

The various challenges the employees at the school encountered created a break between the vision and reality. Whereas the vision rested on the idea that the students would be able to move between subjects and teachers following students’ needs to solve the learning mission, the formal requirements to follow a set timetable planned a year in advance led to a different reality. One participant called this “a hybrid version,” and another said that “we´ve landed on something in between.” Some felt disillusioned, as illustrated in the following quote:

… we are now talking about the framework for the learning mission; it is clear that if the students are expected to move to different classrooms and have the Norwegian teacher first and second lesson, then the English teacher in the third, fourth, and fifth, and the program subject teacher in the sixth, seventh, and eighth, then the whole point of the learning missions is gone.

Many of the challenges the employees encountered in the school’s development process were because of the limitations of the traditional structures in schools, such as the timetable, the set-up of the classroom, and the formal expectations (e.g., number of hours per school subject). Although structure can be useful for creating order, it can also limit flexibility. The school aimed to let the students partake in shaping their school day; to reach this goal while also working around the challenges and limitations they experienced, it was necessary to think anew. Which solutions and opportunities have helped the employees toward developing the new model?

Even though the COVID-19 measures had created a challenging time in the school’s development project, the digital competency the teachers acquired and practiced through the lockdown periods opened new possibilities. Some had experienced that students who normally received poor grades had blossomed during the lockdowns. One teacher wondered whether this was because when working at home those students were less prone to observe how fast the others were solving the assignments in comparison to themselves and, consequently, were able to stay more focused and motivated than before.

Furthermore, even though the teachers in general had followed their students in the set class periods through online meetings, communication with students and the lecture plan had been more flexible during lockdown periods. This allowed both the students and teachers to experience a different school day situation in which learning and assessment happened while the students were spread in many different locations. The COVID-19 period opened new opportunities for letting students travel to off-school sites and manage their time more freely. One participant reflected upon this:

There were some gains we received when we had home school during which we dared to let the group loose on their own, and then, you did not even need to be at the school. This makes me think that then there must be an opening for making the timetable more flexible.

In short, the experiences during the COVID-19 period showed the participant that a more flexible timetable was positive.

One solution all the participants agreed that had provided more, rather than less, flexibility was the interdisciplinary topics introduced with the new National Curriculum in Norway. Whereas before the school’s development project, interdisciplinary cooperation was most often initiated with the various goals of the specific subjects and then coordinated into interdisciplinary projects, the starting point was now the interdisciplinary topics, which were subsequently tied to the specific subjects. The fact that the overarching topics and subject-specific goals were decided in the National Curriculum made it easier to plan interdisciplinary projects in advance because these could be plotted into the annual plan without the preliminary mapping of overlapping subject-specific goals. For some learning missions, students and teachers worked for more than three weeks on each of the three interdisciplinary topics. One participant explained that, by starting more systematically with the Core Curriculum, the understanding of how this is connected to the specific subjects had also developed: “One uses the Core Curriculum more systematically and gets a better understanding of the prescribed goals in it; then, every subject is placed more in its rightful place, if I can put it like that?”

In the learning missions, in which they started with the interdisciplinary topics and subsequently decided which subject-specific goals would be included, made the school spend more time on these topics than would have been done if the school had followed the traditional approach. It is certainly true that the interdisciplinary topics made it easier to plan and coordinate interdisciplinary learning missions for teachers and their leaders.

When asked about the positive aspects of the new pedagogical model as it was practiced, the most common answer among the participants revolved around how the new approach enabled the students to understand the connection between various subjects, hence increasing the probability of creating in-depth learning. This was motivating for the teachers, who felt that the students better understood the relevance of what they learned in school. One participant explained how this affected the students:

I experience that the students get a different understanding of which role the various subjects have and what their significance is for what they are going to learn, first and foremost in vocational education, but also in their personal development.

A better sense of relevance was another positive aspect that the participants had experienced through the learning missions as these were practiced. Some of the participants, particularly program subject teachers, experienced how it was advantageous to include elements from entrepreneurship in the learning missions to make them truly relevant. The following quote is an example of how the teachers viewed their real-life practice as optimal:

Participant 1: “I think that it [what students create] has to be used for something; that is the best we can achieve.”

Participant 2 agrees.

Participant 1: “They are going to sell their products in the Christmas market. And then, we are including it in English [the subject], math, and vocational subjects. And then, they have that youth business. They have made it, they make the products, they are there in the middle of it and doing it, and that is very relevant.”

One participant had a dream of designing the learning missions as a form of active citizenship in which what the students did in their subjects in school would benefit the local community, hence giving the students practical experience of contributing to local society. Another emphasized that the learning missions should be useful for the current time and be designed accordingly: “If it is going to be a learning mission, then it is there and then; it has to be something that can be used or, yes, something that will be useful for something, so the timing is super essential. We have to be able to shape it, and it has to be a real mission.” This underlines the value of having the learning missions shaped by both society and the students in contrast to the more traditional dissemination-based model in which the students often follow textbooks.

Another participant explained that the salary the students received through the youth business was motivational:

… to make the instruction close to reality … we have started a youth business … we have received equipment from (anonymized name of the business) that they were done with using and that they were going to throw away, so we got that equipment. And that equipment one can repair and sell, so that leads to them (the students) doing it, it is like a carrot that they are left with something as a result of what they are doing.

Several common core subject teachers experienced that the students appreciated that the subjects were closely linked to the various professions the students were aiming for, as exemplified in the following quote: “I can see that my students appreciate it when I now work more vocationally, that Norwegian and social science … take more into consideration the profession they are in and do not think of Norwegian and social science as isolated.” Meanwhile, a vocational subject teacher expressed the following:

What I think is fun about working with the learning missions is that instead of memorizing theory, you can work on creating an understanding in the students, because retrieving theory today, it´s in books, online, there are academic articles, it´s out in the industry…you can get theory whenever you want, and as a skilled worker today it might not be the theory that you need, but rather to create understanding for the profession.

This participant experienced that learning missions created a framework for building understanding rather than an emphasis on specific and common knowledge. This was interesting because the focus shifted toward a general development of understanding, but also a general move away from shared, common knowledge as the path to reach such an understanding.

Analysis and discussion

In all the interviews, the participants reflected on which solutions would be the most suitable to move the school’s development project closer to the intended vision. The message most clearly communicated through the interviews was that the complex structure administering everyday life in upper secondary schools was not designed to make room for student participation, active learning, and increased interaction with the local community. Even though the National Curriculum had introduced interdisciplinary topics that provided more flexibility in terms of coordinating and planning interdisciplinary learning missions, this elasticity was not reflected in the regulations that the school’s administrative system represented to the participants. The feeling of being restricted by the complex structure created by the teacher’s employment contract and the system that monitored students’ presence, was a hindrance to transitioning toward a more student-centered and interdisciplinary pedagogical approach. This does not mean that there was no opportunity to further develop the model within the framework currently in place. As expressed by one of the participants, these aspects cannot be changed at the school level, so the path forward will have to focus on what can be done within the existing framework at the school level. However, illuminating practical and structural challenges is also important as resolving such aspects would probably make it easier for the practitioners to develop new practices.

The transition to active interdisciplinary learning requires the students and employees at the school to work differently than what they have been used to; in many ways, the employees at the school were carrying out groundbreaking work. For the participants, one of the main arguments for transitioning to a more interdisciplinary and student-centered approach was that the student would experience the school as relevant, both here and now and for the unpredictable future the school is preparing the student for. The flip side of this was that the success of the new pedagogical approach could be measured by the degree to which the students experienced that the learning missions were indeed relevant. Many of the participants reflected upon what elements of the learning missions made the new approach relevant and how it could be improved to make it even more relevant. The aspect of usefulness in the real world was continuously considered key to creating a sense of meaningfulness and relevance for the students.

The breakage with traditional aspects that the ambition of the school entailed would, in Bernstein’s framework, be conceptualized as a change toward both a weaker classification and weaker framing. It would be a weaker classification because the goal of the model was to make it more relevant for the particular student through a thematic and interdisciplinary approach, hence blurring some of the lines between the different subjects. It would be a weaker framing because the goal was to move from the traditional dissemination-based method toward a more flexible and student-centered way of organizing life in school, one in which the students themselves would have more freedom to choose where, how, and when they would work on the various missions.

As predicted by Bernstein’s framework, the intended shift toward a weaker classification and weaker framing encountered resistance. The participants observed that it was not fully possible to create weak classification and, hence, give the students more freedom to make decisions while also following the formal requirements controlled by the administrative computer program and the classroom and workshops available. Therefore, students’ freedom of choice in terms of how, when, and where they were taught was also limited, meaning that, in their case, classification and framing were interconnected and stronger than expected. The result was a middle place in which one ended up with a mix of the two, as illustrated in the image below

Even though the participants had experienced that they had not been able to move on to ongoing practice as much as intended, more teacher than before moved away from a dominantly subject-specific, dissemination-based approach to a more interdisciplinary approach. This was made easier by the interdisciplinary topics introduced with the new national curriculum. The transition had shown the participants that the students were able to see more connections between the subjects rather than understanding the subjects as separate from each other. This discovery and contiguous positivity among the employees towards the interdisciplinary learning missions reiterate recent research on how a majority of teachers considered interdisciplinary teaching key to enhancing relevance, connection to society outside the classroom, and learning outcomes (Biseth et al., 2022). Furthermore, the participants found that giving flexibility was easier when they replaced the old organizational structure with a process-related one. This aligns with Bernstein’s prediction that the focus will shift from what they learn to how they learn.

According to Bernstein, a weaker classification and framing will strengthen the student’s participation. Moving in such a direction would align with the following ambition in the national Core Curriculum: “The pupils must experience that they are heard in the day-to-day affairs in school, that they have genuine influence, and that they can have an impact on matters that concern them” (Ministry of Education and Research, 2017, 1.6). It is important to emphasize that for Bernstein, weaker classification and framing also give the teacher more freedom, even though the teacher´s role is more authoritative when classification and framing are strong. Put simply, if day-to-day affairs are too directed by tradition, framework and control measures, it is more complicated for teachers and students to impact matters that concern them. This may be one reason why some participants experienced flexibility during the COVID-19 measures, as a period in which they dared to give the students more freedom. This is similar to the conclusion drawn in another study on the impact of corona measures in primary and lower secondary schools in a Norwegian municipality (Bubb & Jones, 2020).

The findings in this article provide insight into some specific challenges and opportunities the participants had encountered when working towards complying with the ambitions for the interdisciplinary topics. Although the new curriculum introduced interdisciplinary topics, this did not exist as a category in the school administrative system. This contradiction created frustration for the employees, specifically in how the new curriculum communicated a move toward more flexibility, student participation, and interdisciplinarity, while the new administrative computer program based on the legal and formal requirements provided no framework to fulfill this ambition. In a report on results from an extensive questionnaire to evaluate the implementation of the new curriculum, 63% of participants representing the school owners of upper secondary schools in Norway respond that they not at all or to a small degree adjust subjects and school hour distribution to take care of the interdisciplinary topics. In the elaboration on why this is not done, some of the respondents replied that this is left to the specific schools to decide (Bergene & Solbue Vika, 2022, pp. 38–40). The findings in this article, however, suggest that it is not that simple for individual schools to adjust the subject- and school-hour distribution when the school administrative program and the regulations the program monitors make it very complicated to make such individual adjustments.

Furthermore, no formal assessment was tied to the interdisciplinary topics. Many of the challenges the employees at the school encountered were linked to a tension between the subject-specific assessment expectations and the ambition of creating interdisciplinary topics. The participants strived to seamlessly merge subjects so that the completeness of a problem and interconnections between the subjects would stand out to the students. The students were asked to create an assignment in which they reflected upon the problem they worked with rather than focusing on which part of the information pertained to the individual subjects. However, when the teachers and students assessed the product, they again had to focus on each subject as the assessments were tied to this aspect. The extra layer of competency that had evolved through organizing and solving a task according to relevance rather than subject-specific criteria was not mirrored in the assessments. The experience of working hard to merge the subjects and, subsequently, to unmerge the subjects was time-consuming and frustrating for the participants. The deeper reason for the frustration the participants encountered seems to be that it was confusing to the participants that the ambition communicated through the curriculum was interdisciplinarity, yet the framework for assessing the students was purely subject-specific.

Finally, to move the model onward, the participants ideally would want a more flexible organizational framework and a building structure more adjusted to the new model. Within the hybrid version, however, they identified that a less complex structure and one developed to make space for allowing the students to influence what, how, and where they learned was necessary to allow for a higher degree of student participation and influence. Furthermore, if the students were to experience the new model as meaningful, it would be necessary to give them the experience that active learning in which the students can show a broader spectrum of their lifeworld was relevant, both in terms of usefulness in the real world and by aligning the assessment of the students’ competency with the competency they acquired through the learning missions.

Considering that the goal of the learning missions and the school’s development project was to make the learning more relevant for the individual student and provide an opportunity for students to show their complete competency, it is important to create learning missions that are flexible enough to include the student’s prior knowledge and personality. Only if the teachers themselves have flexibility can they extend flexibility to their students, and this is why the framework for creating a structure cannot be too complex. Furthermore, the students are likely to experience active, student-centered learning as more relevant for them if the assessment and their grades reflect what they have learned through being active.

Conclusion

The participants identified the organizational structures of the school, such as the school administrative system, the building, the assessment, and the set timetable as inflexible measures that impeded the school from moving away from a dissemination-based approach to education. Inversely, the implementation of interdisciplinary topics in the new Norwegian National Curriculum can be seen as an example of a structural change that the participants thought had opened up a new space of opportunities to create interdisciplinary, student-centered learning missions. Even though the new curriculum had opened up more flexibility, the participants experienced that this flexibility was not extended into the regulations, which controlled how time should be spent in school or the assessment norms. This suggests that more similar structural changes would be helpful to enable the growth of pedagogical models that will allow for an increase in student participation, co-determination, and real-life experiences in schools.

In the clash between the school’s ambition and organizational structures fitted for the traditional dissemination-based school structure, the participants found new opportunities to structure learning missions in interdisciplinary topics and improved digital tools and competency. Paradoxically, granted that the school’s ambition was to enhance students´ participation and influence, the employees experienced that the flexibility required to make space for student participation and co-determination in line with the vision was hampered by the complexity of having to joggle the new pedagogical model and traditional structures. The findings led to two key observations that should be further explored to move the learning mission model toward enhanced student participation and co-determination. First, if the school wants to enable more flexibility to include the student’s co-determination and active participation, it is necessary to reduce the complexity of the organizational structures. Second, if the students are to experience active learning as truly relevant, it is necessary that the competency the student has acquired by being active is captured and aligns with the assessments.

Litteraturhenvisninger

Andreassen, S.-E. (2016). Do we understand the curriculum? (Forstår vi læreplanen?) [UiT The Arctic University of Norway]. Munin: Open research archive. https://munin.uit.no/bitstream/handle/10037/9671/thesis_entire.pdf?sequence=3

Andreassen, S.-E., & Tiller, T. (2021). Rom for magisk læring: En analyse av læreplanen LK20. Universitetsforlaget.

Bergene, A. C., & Solbue Vika, K. (2022). Questions for school-Norway: Analysis and results from the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training´s survey in relation with the evaluation of the Subject Renewal (No. 15; p. 96). The Nordic Institute for Studies of Innovation, Research and Education. https://www.udir.no/contentassets/4e546a7ee2744062adf940c1a3ef3292/nifu_2022_sporring_fagfornyelsen.pdf

Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Schmid, R. F., Waddington, D. I., & Pickup, D. I. (2019). Twenty-first century adaptive teaching and individualized learning operationalized as specific blends of student-centered instructional events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 15(1–2), e1017. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1017

Bernstein, B. (1973). On the classification and framing of educational knowledge. In Knowledge, education, and cultural change. Routledge.

Biseth, H., Seland, I., & Huang, L. (2021). Strengthening connections between research, policy, and practice in Norwegian civic and citizenship education. In B. Malak-Minkiewicz & J. Torney-Purta (Eds.), Influences of the IEA Civic and Citizenship Education Studies (pp. 147–159). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71102-3_13

Biseth, H., Svenkerud, S. W., Magerøy, S. M., & Rubilar, K. H. (2022). Relevant Transformative Teacher Education for Future Generations. Frontiers in Education, 7. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.806495

Blaskó, Z., da Costa, P. D., & Vera-Toscano, E. (2019). Non-cognitive civic outcomes: How can education contribute? European evidence from the ICCS 2016 study. International Journal of Educational Research, 98(2019), 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.07.005

Boese, V., Alizada, N., Lundstedt, M., Morrison, K., Natsika, N., Sato, Y., Tai, H., & Lindberg, S. (2022). Autocratization changing nature? Democracy report 2022. Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem). https://v-dem.net/media/publications/dr_2022.pdf

Bonwell, C., & Eison, J. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom [George Washington University]. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED336049.pdf

Bubb, S., & Jones, M.-A. (2020). Learning from the COVID-19 home-schooling experience: Listening to pupils, parents/carers and teachers. Improving Schools, 23(3), 209–222.

Chi, T. H. M., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 219–243.

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2022). Democracy Index 2021: The China challenge. https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2021/

Fullan, M. (2020). System change in education. American Journal of Education, 126(4), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1086/709975

Fullan, M., Quinn, J., & McEachen, J. (2018). Deep learning: Engage the world. Change the world (Kinde). Sage Publications.

Hanney, R., & Savin-Baden, M. (2013). The problem of projects: Understanding the theoretical underpinnings of project-led PBL. London Review of Education, 11(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14748460.2012.761816

Hoskins, B., Saisana, M., & Villalba, C. M. H. (2015). Civic competence of youth in Europe: Measuring cross national variation through the creation of a composite indicator. Social Indicators Research, 123(2), 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0746-z

Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2015). NMC Horizon report K-12 edition. The New Media Consortium. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED593612

Karseth, B., Kvamme, O. A., & Ottesen, E. (2020). Fagfornyelsens læreplanverk: Politiske ambisjoner, arbeidsprosesser og innhold (No. 1). https://www.uv.uio.no/forskning/prosjekter/fagfornyelsen-evaluering/

Kosberg, E., & Grevle, T. E. (2022). Review of International civic and citizenship survey data analyses of student political efficacy. In R. Desjardins & S. Wiksten (Eds.), Handbook of civic engagement and education. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2017). Core curriculum – values and principles for primary and secondary education. Laid down by Royal decree. The National Curriculum for the Knowledge Promotion 2020. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng

Ødegård, G., & Svagård, V. (2018). Hva motiverer elever til å bli aktive medborgere? [What motivates students to become active citizens?]. Tidsskrift for Ungdomsforskning, 18(1), 28–50. https://journals.oslomet.no/index.php/ungdomsforskning/article/view/2995

OECD. (2022). Trends Shaping Education 2022. OECD Publishing. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/trends-shaping-education-2022_6ae8771a-en

OECD Future of education and skills 2030: Learning Compass 2030, (pp. 1–150). (2019). OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf

Ottesen, E., Colbjørnsen, T., & Gunnulfsen, A. E. (2021). Fagfornyelsens forberedelser i praksis: Strategier, begrunnelser, spenninger (No. 2; p. 114).

Prince, M. (2004). Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research. Journal of Engineering Education, 3, 10.

Sant, E. (2019). Democratic Education: A Theoretical Review (2006–2017). Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 655–696. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319862493

Schleicher, A. (2015). Schools for 21st-Century Learners: Strong Leaders, Confident Teachers, Innovative Approaches | READ online. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/schools-for-21st-century-learners_9789264231191-en

Shekhar, P., Borrego, M., DeMonbrun, M., Finelli, C., Crockett, C., & Nguyen, K. (2020). Negative student response to active learning in STEM classrooms: A systematic review of underlying reasons. Journal of College Science Teaching, 49(6), 45–54.

Sohl, S., & Arensmeier, C. (2015). The school’s role in youths’ political efficacy: Can school provide a compensatory boost to students’ political efficacy? Research Papers in Education, 30(2), 133–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2014.908408

Swain, J., & King, B. (2022). Using Informal Conversations in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 16094069221085056. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221085056

Tjora, A. (2019). Qualitative Ressearch as Stepwise-Deductive Induction. Routledge.

Westheimer, J. (2015). What Kind of Citizen? Educating Our Children for the Common Good (Kindle edition). Teachers College Press.