Læreres profesjonsfaglige digitale kompetanse – den forsømte ledelsen av teknologirike klasserom?

Kunnskap om hvordan lærerutdanningen kan bidra til å utvikle lærerstudentes profesjonsfaglige digitale kompetanse er avgjørende for å sikre at lærerstudenter er forberedt på å møte framtidens behov.

Forskningen som blir presentert i denne artikkelen har som mål å øke kunnskapen om hvordan man kan konseptualisere klasseledelse som en tverrfaglig kompetanse innenfor profesjonsfaglig digital kompetanse. Vi benytter to ulike konseptuelle rammeverk for læreres profesjonsfaglige digitale kompetanse og en mindre del empiriske data for å beskrive spørsmål om praktisering av klasseledelse. De to tilnærmingene inkludererer TPACK-modellen («Technical Pedagogical Content Knowledge»), inkludert kunnskap om teknologi, pedagogikk og innhold så vel som om kontekst, og rammeverket «the European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators» (DigCompEdu), som peker på profesjonsfaglig digital kompetanse i form av seks lærerspesifikke kompetanser. To øyeblikksbilder fra klasserom med lærerstudenter i praksis blir analysert, og analytiske styrker og svakheter ved de to tilnærmingene blir analysert. Øyeblikksbildene indikerer at de konseptuelle rammeverkene er ulike med hensyn til å ta opp spørsmål om klasseledelse i teknologirike klasserom, noe som er en grunnleggende del av læreres profesjonsfaglige digitale kompetanse. Vi anbefaler videre forskning om relevante begreper om klasseledelse, som igjen kan bli brukt som indikator for læreres profesjonsfaglige digitale kompetanse og øke den analytiske styrken i de konseptuelle rammeverkene i utdanningsforskning.

Teachersʼ Professional Digital Competence – The Neglected Management of Technology-rich Classrooms?

Understanding how teacher education programmes can contribute to develop student teachersʼ professional digital competence is crucial for ensuring that student teachers are prepared to meet the future needs of society.

The research presented in this article aims to gain increased knowledge on how to conceptualise classroom management as a transdisciplinary competence within professional digital competence (PDC). We employ two different conceptual frameworks on teachersʼ PDC and a small set of empirical data to illustrate classroom management issues in teaching practice. The two approaches include the Technical Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) model, including technological, pedagogical and content knowledge as well as contextual knowledge, and the European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu), which illustrates PDC in terms of six educator-specific competences. Two snapshots of student teachersʼ classroom practices are analysed and the analytic strengths and weaknesses of the two approaches are demonstrated. The snapshots indicate that the conceptual frameworks differ in addressing issues of classroom management in technology-rich classrooms, which is a crucial part of teachersʼ PDC. We recommend further investigation into relevant classroom management concepts, which, in turn, can be used as indicators of teachersʼ PDC and increase the analytic strength of the conceptual frameworks for education research.

Introduction

Teacher education programmes include a large variety of subject areas, but lack a common vision of what constitutes a professional teacher (Hammerness, 2013) and the role of transdisciplinary learning processes in teacher education (Caspersen et al., 2017; Dahl et al., 2016). This research aims to increase knowledge about student teachersʼ transdisciplinary digital competence. Understanding how teacher education programmes can contribute to develop student teachersʼ professional digital competence (PDC) is crucial for ensuring that student teachers are prepared to meet the future needs of society (Johannesen & Øgrim, 2020).

The understanding of teachersʼ PDC is under continuous investigation (Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, 2018; Johannesen et al., 2014; Lund & Aagaard, 2020; Mishra & Koehler, 2006). This research focuses on what constitutes such competence. The research directs its attention towards student teachers, as their professional acumen should ideally align with the digital competence of in-service teachers. Consequently, when discussing the competence of teachers in the context of this study, it is equally applicable to the competence of student teachers. Several frameworks have been developed to understand teachersʼ PDC, such as within the Technical Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) community (Caniglia & Meadows, 2018; Feng et al., 2017; Ozden et al., 2016). However, such frameworks tend to support descriptive rather than analytic research and are often based on self-reported data (Kimmons & Hall, 2018; Pareto & Willermark, 2018; Siddiq et al., 2016). Several of these studies (Koh et al., 2014; Yeh et al., 2014) lend themselves to Mishra and Koehlerʼs (2006) TPACK framework by expanding its scope to cover actual use in practical situations (such as TPACK practical) and by providing references for future surveys or measurement construction (Yeh et al., 2014). Measuring competence in terms of self-reported data is challenging. Not only is there a challenge in defining what PDC entails, but also in developing relevant assessment instruments that mirror the authentic tasks that teachers engage in (McGarr & McDonagh, 2019). Furthermore, self-reported data tends to be influenced by intentions as well as actual practice of the ones responding.

Harris et al., (2010) address these challenges by focusing on the practical use of technology, such as investigating lesson plans and analysing them according to curriculum goals and strategies. While conceptual frameworks often focus on skills and knowledge of using certain technologies, there is less focus on pedagogical use of technologies and how to use technology for developing 21st century skills, such as creativity, communication, collaboration and critical thinking (OECD, 2018).

Additionally, there are still many unanswered questions regarding classroom management in technology-rich classrooms, such as negative pupil behaviour when using tablets in the classroom (Durak & Saritepecİ, 2017) and how the introduction of technology into classrooms changes the dynamics of the classroom (Bolick & Barels, 2014). A systematic review of technology in classroom management (Cho et al., 2020) reveals that technology in classrooms can be seen as tools for managing the classroom rather than tools for pupilsʼ learning.

In this study, we investigate two existing overarching conceptual frameworks and their capacity to describe classroom management as part of student teachersʼ PDC in practice placement. We ask:

- In what ways do the frameworks TPACK and DigCompEdu emphasise classroom management for teachers?

- In what ways do the frameworks emphasise classroom management applicable to typical student teacher practices?

To address these research questions, we employ the two conceptual frameworks on a small set of data and investigate the ways in which they work as tools for describing and understanding two snapshots of student teachersʼ classroom management in practice placement.

Classroom management

Kounin (1970, as cited in Hastie et al., 2007) reports that the ways teachers handle misbehaviour are not the keys to successful classroom management; instead, the key is what teachers do to prevent misbehaviour in the first place. The technology-rich classroom, filled with tempting digital tools, creates new situations in which matters of discipline might seem relevant again. Doyle (1986) describes student and teacher behaviour as mutually influencing; changes in student behaviour have direct consequences for the academic work and thus require responses from the teacher. For example, if students pay attention to playing with digital tools, the teacher will act to restore focus, thereby suspending attention to academic work. The agendas that students have for work (and play) in the classroom functionally impact their work (Allen, 1986). In particular, social systems strongly reinforce the understanding of how students negotiate task demands with their teachers (Carlson & Hastie, 1997; Hastie et al., 2007). In a digitalised society, the distinction between social and scholarly lives is blurred, and such task negotiations have become even more relevant.

Classroom management emphasises teachersʼ competence in organising work so that students and teachers have peace of mind (Kounin, 1970; Ogden, 1987). On the other hand, the teacher effectiveness tradition focuses on facilitating good relations between teachers and students (Lillejord et al., 2010; Nordahl, 2013) and on facilitating good learning processes, with an emphasis on the importance of academic content (Christensen, 2008). Here we understand classroom management in line with Christensen and Ulleberg (2020) as the relationships between students and teachers, both as individuals and as part of a community, as well as in the setting of academic content.

Plauborg et al. (2010) have summarised research on teacher behaviour in three areas: 1) organising of classroom activities, such as lesson plans, coherence in content and methods, well-orchestrated transitions, variation in teaching methods and high expectations, 2) facilitating learning environments, such as the development of a caring learning environment, extensive use of feedback and avoidance of pre-set student categorisation, and 3) facilitating teacher–pupil relationships and communication, such as appreciative communication and dialogic teaching. In line with this categorisation Cho et al. (2020 identify three schools of thoughts in a systematic review: ecological, behavioural and social-emotional. However, the number of studies that have examined these conditions in technology-rich classrooms is limited (Krumsvik, 2014; Bolick & Barels, 2014; Meinokat & Wagner, 2022). Nevertheless, we have identified some research on classroom management in technology-rich environments.

There are different ideas about how to understand classroom management, for example ecological ideas emphasizing organizing rooms and routines (Cho et al., 2020), or behavioural ideas (Gunnars, 2021) introducing systems of support or response to students. Yet, it is not clear how digital technologies as videos, simulations, or apps can support ideas about classroom management (Cho et al., 2020).

A review of scholarly research exploring the confluence of classroom management and technology indicates a predominance of studies focused on classroom management, with a comparatively limited emphasis on the intersection of these two fields (Meinokat & Wagner, 2022). Several studies appear to concentrate primarily on the potential negative impacts or disruptions caused by the integration of digital technologies into classroom management (Selwyn, 2016; Henderson et al., 2017; Aagaard et al. 2023).

In conclusion, the perspective of teachers on both digital technology and classroom management is of critical importance (Egeberg et al., 2021; Farkhani et al., 2022; Johler et al., 2022). Teachers generally harbour positive attitudes towards the integration of digital technologies in teaching, yet the implementation of these technologies in classroom management may be impeded by factors such as insufficient resources, limited time, or a lack of technological infrastructure (Pratolo & Solikhati, 2021).

Encouragingly, numerous studies have indicated that pre-service teachers can enhance their classroom management skills through targeted interventions in teacher education. The literature suggests that such training and instruction can have a significant positive impact on pre-service teachersʼ classroom management abilities (Dicke et al., 2015).

Various modes of delivering this training exist, ranging from traditional classroom-based instruction to innovative virtual reality courses designed to support the development of classroom management competencies (Seufert et al., 2022). The focus of the training can be tailored to address specific areas of need, such as reducing pre-service teachersʼ anxiety related to teaching responsibilities (Theelen et al., 2022)

Given the limited body of research concerning classroom management within technology-rich environments, it becomes compelling to delve into the experiences articulated by Giæver et al. (2020) regarding instruction in such classrooms. Accordingly, in the present study, we will adopt Plouborgʼs acclaimed categories of classroom management and apply them to scenarios situated in technology-rich classrooms, as depicted in Giæver et al. (2020). Based on the categories from Plauborg et al. (2010), Giæver et al. (2020) emphasise three areas: 1) the teacherʼs organisation of classrooms with digital tools, such as the pupilsʼ and the teacherʼs physical location, 2) the teacherʼs facilitation of teaching and learning with digital tools, such as planning, presentations and feedback, and 3) the teacherʼs work with the development of relationships in technology-rich classrooms, such as encouragement, feedback and customisation of tasks (Giæver et al., 2020).

Two conceptual frameworks for understanding teachersʼ digital competence

A previous study of three frameworks for teachersʼ PDC revealed that the frameworks failed to sufficiently illuminate classroom management issues (Johannesen et al., 2019). In this study, we have chosen to further investigate the TPACK framework, which has been extensively operationalised into measurable indicators of teacher knowledge (Harris et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 2009), and is widely used in international research on teachersʼ and student teachersʼ PDC. In addition, we have chosen the European DigCompEdu framework (Redecker, 2017), an internationally renowned framework that also addresses the educational setting for teacher competence.

In the following sections, the two conceptual frameworks are presented. The frameworks represent different perspectives for understanding and analysing teachersʼ PDC.

Framework 1: TPACK

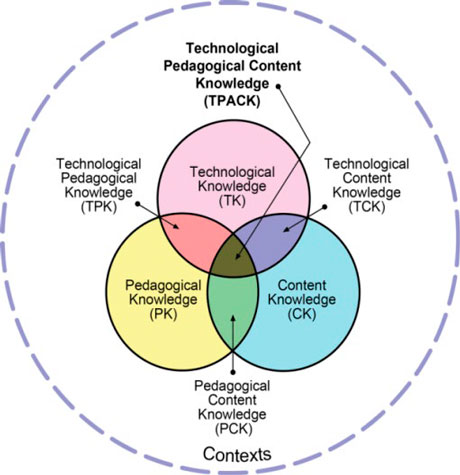

The TPACK model as developed by Mishra & Koehler (2006) and Koehler & Mishra (2009) is based on the concept of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), developed by (Shulman, 1986). The model contains three primary forms of knowledge: content knowledge (CK), pedagogical knowledge (PK) and technological knowledge (TK) (see Figure 1). The relationships between these forms of knowledge are scrutinised through four intersections: Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), technological content knowledge (TCK), technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK), and in the centre, technological and pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK). This paper emphasises the latter three intersections that are most relevant when analysing the role of technology in teaching. TCK is how teachers show knowledge of combining class content with technology. TPK is how teachers use their knowledge through applying technology in their teaching. TPACK depends on the overlap of TPK and TCK (e.g. the relevant technology must be chosen and used in a way that supports teachersʼ understanding of the content).

Framework 2: DigCompEdu

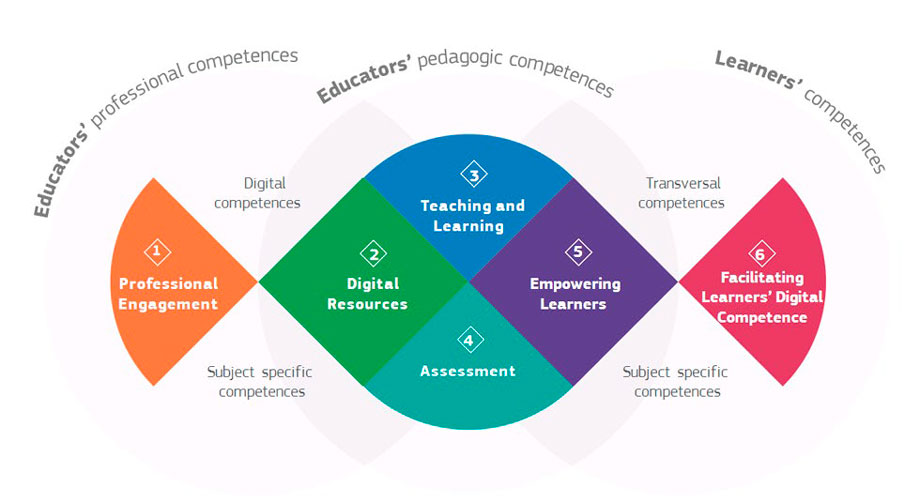

The DigCompEdu framework (Redecker, 2017) illustrates PDC in terms of three different competence areas for educators and learners: educatorsʼ professional competences, educatorsʼ pedagogical competences and learnersʼ competences (see Figure 2). These competence areas are divided into six specific competences. Within educatorsʼ professional competences, we find 1) professional engagement in using digital technologies in communication and collaboration and professional development, as well as digital and subject-specific competences. The educatorsʼ pedagogical competences comprise four areas: 2) creating and sharing digital resources, 3) managing and orchestrating the use of digital technologies in teaching and learning, 4) using digital technologies and strategies to enhance assessment and 5) using digital technologies for empowering learners. Finally, the framework indicates that educatorsʼ competences embrace learnersʼ competence and how to 6) facilitate learnersʼ digital competences as well as subject-specific and transversal competences. These six competence areas are divided into a total of 22 sub-fields. Furthermore, the descriptions of the six competence areas are operationalised into activities described to help educators foster quality teaching and learning strategies. To support educators in developing their PDC, the framework rests on a progression model and a rubric for self-assessment in each of the areas.

Methodology

To answer the first research question, the two frameworks are analysed according to the three areas of classroom management suggested by Giæver et al. (2020). This analysis identifies some indicators for classroom management in technology-rich classrooms. Two snapshots from classroom practice are then used to illustrate the ways in which student teacher practice in technology-rich classrooms correlates with these indicators.

Identifying classroom management in the two conceptual frameworks

The two frameworks address different perspectives on PDC. The TPACK framework mostly describes the types of competences needed by educators and how these relate to each other, while the DigCompEdu framework presents detailed competence descriptors needed in education, as well as activities for gaining these, and furthermore puts the competence descriptors into a system of self-assessment.

Neither of the two frameworks explicitly mentions or describes classroom management. The richness of details provided by these frameworks presents a challenge when attempting to scrutinize them for elements related to classroom management. Nevertheless, in an effort to discern traces of classroom management within them, we have elected to review these frameworks using the categories established by Giæver et al. (2020) as an analytical lens.

The selected indicators employed in this study were identified independently by each of the authors of this article and then discussed and agreed upon.

There may be different ways to describe the content of TPACK. In this paper, TPACK is operationalised through instruments developed for measuring TPACK, both as self-reported data (Schmidt et al., 2009) and as observed data (Harris et al., 2010). From Schmidt et al. (2009), we employ the indicators given in Table 8 Factor Matrix for Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (p. 135). From Harris et al. (2010), we use the Technology Integration Assessment Rubric found in the Appendix of the article. These instruments entail indicators that can be identified as addressing classroom management issues.

Appendix A presents the identified criteria related to classroom management, as found in these two sources. From the DigCompEdu framework, we have identified classroom management issues from the indicators for a digitally competent educator (see Appendix B).

Data collection from student teacher practice

As stated previously, studies investigating PDC among teachers and student teachers predominantly rely on self-reported data (Kimmons & Hall, 2018; Pareto & Willermark, 2018; Siddiq et al., 2016). However, the present study distinguishes itself by utilizing observational data, thereby capturing the practical actions and experiences of student teachers during their practice placement. This approach provides a window into the concrete behaviours exhibited by these student teachers, moving beyond mere subjective intentions.

Approximately 115 classes have been observed, encompassing around 20 groups of student teachers across 15 placement schools. Given this vast pool of data, numerous snapshots could have been selected for closer examination. However, we have opted to present two specific snapshots that effectively portray typical and illustrative situations. The rationale behind this selection lies in the fact that both snapshots exemplify common classroom management issues in technology-rich environments and shed light on genuine instances of student teachersʼ PDC.

All classrooms were observed during the student teachersʼ practicum in primary schools. The classrooms were equipped with the kind of technology one could anticipate meeting in an ordinary Norwegian classroom, and were not chosen according to the schools being engaged in any kind of digitalisation programme, or having a focus on using digital tools in teaching and learning.

The researchers used fieldnotes, combined with a predefined observation form addressing activities and classroom management matters, such as organisation of classrooms, facilitation of teaching with technology, and management of technical and relational issues (based on categories from Giæver et al., 2020): see Appendix C. After each observation, the researchers compared their notes and recorded a summarising conversation about what they had observed during the session. The observed practice, utterances and opinions were then analysed according to the TPACK and DigCompEdu frameworks, to uncover in what ways these frameworks support classroom management issues.

Snapshots

From the observation of the student teachers, several findings emerged as candidates for investigating whether the frameworks presented above are relevant to illustrate practical issues in classroom management. The next two paragraphs present brief snapshots of the two situations as an introduction to the forthcoming finding and discussion sections.

Snapshot A: Student Teachers Using Tablets in a Norwegian Language Class for 5th Grade

A student teacher was teaching approximately 20 5th graders in the Norwegian language. In the classroom, there was access to an ordinary whiteboard, partially covered by a digital whiteboard connected with AppleTV or HDMI cable. The student teachers and pupils all had their own iPads.

Several examples illustrate how the student teacher organised the classroom. They connected the tablet to the digital whiteboard and, after some technical struggle, managed to mirror the iPad on the whiteboard screen. They used iThought (a software for mind mapping) to present the lesson plan. At this school, iThought is used by all teachers both for the planning of lessons and for presenting activities and goals to the pupils via the whiteboard screen.

At the start of the class, the pupils had their tablets packed down in their bags. However, after an introduction to the topic, the pupils could use their tablets to work on a task. After working for approximately 30 minutes, the student teacher told there were 10 minutes left and then later, 1 minute.

As for the facilitation of teaching and learning with digital tools, the student teacher asked the pupils to use different applications in their work. The pupils were supposed to write a personal story, and the student teacher asked them to use a premade template. This template was not known to the pupils, and the student teacher used their private tablet to show where to find the template and how to use it.

In terms of pupil–teacher interactions, the student teacher instructed the pupils to work quietly during the task. At the conclusion of the class, pupils were directed to close their tablets, thereby displaying the “apple up” sign.

Snapshot B: Student Teacher Using Tablets in a Mathematics class for 10th Grade

A student teacher was teaching approximately 25 10th graders in mathematics. There was access to a digital whiteboard; the pupils had their own iPads, and the student teacher had an iPad connected to the digital whiteboard.

In organising the classroom, the student teacher used a tablet, and the tablet screen was mirrored on the digital whiteboard. The student teacher used MS PowerPoint to present the lesson plan to the pupils. It must be noted that these student teachers did not have access to the school infrastructure and might therefore not be using OneNote, as the placement teacher would have done.

The pedagogical methodology employed by the student teacher adhered to a cyclical pattern: an example was presented on the digital whiteboard, the pupils worked individually in their notebooks and then reporting by showing outcomes on the iPad screens. This way of integrating technology for presenting the pupilsʼ individual work and joint review of the tasks was commonly used in mathematics teaching in this class.

During the class, there were some challenges with access to the software due to administrative changes in the school district. Specifically, some pupils had trouble accessing one of the assignments. This was solved by asking another pupil to “AirDrop” the assignment.

In addition to presenting examples, the student teacher displayed some exercises on the digital whiteboard for the pupils to solve.

The student teacher did not seem to be aware of an ever-increasing share of the pupils who did not work with the exercises but were busy with completely different things. By the end of the class, the student teacher asked the pupils to lay their heads on their desk and show their thumbs up, down or sideways to show their overall judgement of the class, their own engagement and if they had learned anything new.

Findings and analysis

In analysing the two forwarded frameworks, we rest our arguments on the indicators identified from the frameworks (Appendix A and B) and discuss how these indicators are relevant to illuminate classroom management dimensions of student teachersʼ PDC.

Teachersʼ organisation of classrooms with digital tools

The way the teacher organises the physical classroom indicates the kind of learning activities supported and arranged for (Giæver et al., 2020). In both snapshots, the classroom setting was organised with a 1:1 tablet and a whiteboard screen to mirror the student teachersʼ tablets. In addition, the whiteboard screen was used as a blackboard. The installed infrastructure was arranged for audio via speakers connected to the whiteboard. The classrooms were organised in a traditional way, with the pupils heading towards the whiteboard screen.

When looking into the instruments offered by TPACK research, neither Schmidt et al. (2009) nor Harris et al. (2010) present indicators that support teachers in reflecting on how to set up a classroom. There are indicators addressing how to select technologies (Appendix A, #1.1); however, they do not elaborate on how to set up the classroom when using 1:1 technology. The DigCompEdu framework addresses how to set up learning sessions (Appendix B, #3a). However, as with the TPACK framework, the DigCompEdu framework is not explicit regarding the physical organisation of the classroom.

Another organisational issue that emerges from the data pertains to the handling of technical problems. In Snapshot A, the student teacher struggled to mirror the iPad on the whiteboard screen. In Snapshot B, we observed the pupilsʼ difficulties with subscription access to digital learning resources. The instruments offered in TPACK do not address these kinds of classroom management issues on an aggregated level (Appendix A), only when measuring pure technical skills. DigCompEdu, however, has indicators for this, when addressing the issue of having forseen learnersʼ need for guidance (Appendix B, #3d) and to identify and solve technical problems when operating devices and using digital environments (Appendix B, #6d).

Teachersʼ facilitation of teaching and learning with digital tools

Planning for lessons in a technology-rich environment entails having a plan for use and non-use of digital tools as well as being ready for unforeseen events (Giæver et al., 2020). The two snapshots show that the student teachers used technology to present the lesson plan and organise the lessons.

Schmidt et al. (2009) present several indicators related to TPACK for how to choose and teach with technology, but no indicators for lesson planning with technology support. Harris et al. (2010), however, present an indicator that might include planning, namely to what extent technology use supports instructional strategies (Appendix A, #2.2). In this sense, TPACK addresses the importance of planning for a technology-rich classroom.

DigCompEdu also presents indicators that address the facilitating of teaching and learning in technology-rich environments. The indictors stating the importance of reflecting on the effectiveness and appropriateness of the digital pedagogical strategies and flexibly adjust methods and strategies (Appendix B, #3c) address the planning process, but do not mention the use of technology in this matter.

In Snapshot B, we observed the use of a repeating scheme for organising teaching using digital technology. Looking into the frameworks analysed in this article, we see that TPACK presents several indicators for considerations about when and for what purposes digital tools work well, such as I can choose technologies that enhance the content for a lesson (Appendix A, #1.3); I can select technologies to use in my classroom to enhance what I teach, how I teach, and what the students learn (Appendix A, #1.1) ; and technology selection(s) are compatible with curriculum goals and strategies (Appendix A, #2.3). Likewise, DigCompEdu presents indicators, such as select and employ digital pedagogical strategies which respond to learnersʼ digital context (Appendix B, #5a) and reflect on the effectiveness and appropriateness of the digital pedagogical strategies and flexibly adjust methods and strategies (Appendix B, #3c), which underpin the importance of these kinds of classroom management issues.

Teachersʼ work with the development of relationships in technology-rich classrooms

Establishing good routines for behaviour in a technology-rich classroom is essential in building a good learning environment and good teacher–pupil relationships (Giæver et al., 2020). In both snapshots, we observed student teachers having routines for order and discipline. In Snapshot A, the student teacher used “Apple Up” as a way of getting the pupilsʼ attention and telling them to stop using the iPad. In Snapshot B, the student teacher asked the pupils to put their heads on the desk, thereby telling them that they should finish their work and concentrate on what the student teacher said.

The indicators identified from the TPACK framework do not specify these kinds of classroom management issues. DigCompEdu addresses these issues when presenting indicators, such as to monitor studentsʼ behaviour in digital environments in order to safeguard their wellbeing (Appendix B, #6b).

In Snapshot B, we observed that the student teacher failed to see and follow up on the pupils who did not pay attention to the schoolwork. Having internet available demands ever-more follow-up by the student teacher. None of these kinds of classroom management issues are addressed within the TPACK framework or its indicators. A couple of the indicators given by DigCompEdu address topics related to these issues, such as to be aware of behavioural norms and know-how while using digital technologies and interaction in digital environments (Appendix B, #6a) and to react immediately and effectively when learnersʼ wellbeing is threatened in digital environments (Appendix B, #6c).

Identified classroom-management issues are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of main findings.

|

Snap shot issues |

TPACK indicators |

DigCompEdu indicators |

|

Physical organising of classroom |

No |

No |

|

Handling technical problem |

No |

Yes |

|

Planning for technology use |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Purpose of using digital tools |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Routines for order and discipline |

No |

Yes |

|

Follow up of pupils in classroom |

No |

Yes |

Discussion – the analytic strength of TPACK and DigCompEdu in student teachersʼ placement practice

Drawing upon the three areas outlined by Giæver et al. (2020), this discussion examines the presentation of classroom management issues within the two distinct frameworks. Firstly, it is noteworthy that neither framework offers explicit indicators for teachersʼ organisation of the physical classroom with digital tools.

TPACK does provide guidance on classroom organisation in the context of technology selection indicators, but does not extend this advice to the physical arrangement of the classroom. DigCompEdu, on the other hand, offers insight into the utilisation of digital resources as well as the structuring of learning sessions, activities, and interactions within a digital environment.

An ecological approach to classroom environments is recognised as one of several schools of thought within the field of classroom management (Cho et al., 2020). However, this perspective is not extensively explored in the current body of research. This apparent oversight may be attributable to the rapid evolution of digital technologies, or it could be an issue that is taken for granted.

Considering a sociomaterial view of teaching and learning (Fenwick et al., 2012), there is a risk that the pedagogical and academic potential of consciously planning for the role of technology within the learning context may be overlooked. As Cho et al. (2020) argue, there is a pressing need for a greater understanding of how specific technologies play a role in classroom management, thus highlighting the need for further attention in this area.

Secondly, the facilitation of teaching and learning with digital tools by teachers is partially supported within both frameworks, as they both include indicators for describing teachersʼ planning of teaching and learning with digital tools. These indicators resonate with research suggesting that teachers, in general, exhibit a positive attitude towards technology utilisation in classrooms (Pratolo & Solikhati, 2021), yet they also express anxiety concerning the responsibility this incurs (Theelen et al., 2020). As such, these indicators represent important aspects of the expected competence for teachers in technology-rich classrooms.

However, the management of technical problems within the classroom, as identified in the snapshots and addressed by Giæver et al. (2020), is less evident within these frameworks. Within the TPACK framework, such indicators are not apparent at an aggregated level (see Appendix A). A more detailed examination of the technical dimension of TPACK reveals indicators that address teachersʼ personal digital skills (see Schmidt et al., 2009). Nonetheless, personal digital skills do not equate to possessing the knowledge necessary for handling technical problems in a classroom full of pupils as observers.

In contrast, DigCompEdu does provide indicators addressing such incidents. These unexpected and spontaneous situations are not uncommon for teachers and may recur due to factors such as insufficient resources and a lack of technological infrastructure (Pratolo & Solikhati, 2021). Moreover, a deficiency in training and instruction during pre-service training may undermine student teachersʼ classroom management abilities (Dicke et al., 2015).

Finally, in terms of teachersʼ work with relations and behaviour in technology-rich classrooms, there are notable differences between the two frameworks. TPACK appears to fall short in addressing how to cultivate a classroom culture where technology does not detract from pupilsʼ learning. In contrast, DigCompEdu tackles issues of developing relationships in technology-rich classrooms with an emphasis on safeguarding pupilsʼ well-being. In this regard, DigCompEdu seems to acknowledge this crucial facet of teachersʼ competence in technology-rich classrooms.

The absence of indicators describing the relational dimensions of classroom management in the TPACK model is a significant weakness within the framework. The behavioural aspect of classroom management is often cited as the most critical component (Gunnars, 2021; Christensen & Ulleberg, 2020). Moreover, disturbances and distractions are increasingly recognised as crucial factors in classroom management (Selwyn, 2016; Henderson et al., 2017; Aagaard et al. 2023).

In summary, the TPACK framework is frequently utilised to assess student teachersʼ self-reported knowledge of technology, pedagogy, and content, thereby providing a holistic view of the teaching situation. The frameworkʼs clarity and accessibility make it well-suited for facilitating discussions about the necessary knowledge within a professional community. However, to find practical guidance, one must closely examine how this framework is operationalised and employed in empirical studies, such as those by Schmidt et al. (2009) and Harris et al. (2010). These works offer matrices and questionnaires that define the components of this knowledge.

Despite its widespread use in characterising teachersʼ PDC and measuring their level of knowledge, the TPACK framework does not offer guidelines for developing or improving teachersʼ PDC. These must be sought from other sources. In this respect, the TPACK framework appears to overlook certain dimensions of PDC that we believe are integral to teacher competencies. Furthermore, the lack of sufficient focus on classroom management issues as indicators when measuring PDC diminishes the frameworkʼs ability to identify the full range of necessary competence areas.

In contrast, DigCompEdu is detailed and comprehensive. The framework not only outlines characteristics but also provides prescriptions and guidelines for understanding and developing PDC. The observed utilisation of technology verifies that the DigCompEdu framework addresses several aspects of classroom management, thus encompassing numerous areas of classroom management that are the focus of this study. Nevertheless, the extensive range of issues addressed results in DigCompEdu being less communicative than TPACK.

Conclusions and Further Research

While many studies on teachersʼ PDC rely on self-reflections about teachersʼ plans and intentions for technology use in the classroom, this study is based on observational data. It demonstrates that the frameworks do not explicitly address issues of classroom management in technology-rich classrooms, such as handling unforeseen incidents of technology failure, using technology for preparing and organising teaching sessions, and physically designing technology-rich classrooms.

In this inductive approach, we uncover general issues of technology use in the classroom and, more specifically, classroom management. Furthermore, these practices are interpreted according to the indicators of the two frameworks. In doing so, we have identified issues that are not apparent within the two frameworks.

When working with the two frameworks in a top-down approach (i.e., looking for classroom management issues), the indicators provided by previous research (such as Harris et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 2009) and detailed descriptions of the framework (Redecker, 2017) do not explicitly refer to what is characterised as classroom management issues in Giæver et al. (2020). However, when working in a bottom-up approach (i.e., using student teacher practice as a starting point), one can reflect on the practices and consider whether they can be categorised into more general indicators provided by the frameworks.

This research calls for further inductive studies of classroom practices to investigate the analytical strength of TPACK and DigCompEdu as frameworks for PDC. It would be interesting to supplement this with a sociomaterial perspective on classroom organisation. Given the ongoing debate about the use of mobile phones and tablets in schools and the burgeoning AI revolution, it would be timely to study the impact of different materials used in the classroom, particularly how technology-based materials influence classroom management. This should explore not only how to organise and orchestrate material parts, but also how teaching methods vary and change with different materials. Furthermore, the behavioural and relational dimensions of classroom management in different material settings should be investigated. Through this kind of research approach, we can gain a deeper understanding of the competencies required for classroom management in technology-rich classrooms.

Appendix A

TPACK – Identified CLASSROOM-MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Developed by the authors.

From Schmidt et al. (2009), Table 8

1.1. I can select technologies to use in my classroom that enhance what I teach, how I teach, and what the students learn.

1.2 I can provide leadership in helping others to coordinate the use of content, technologies, and teaching approaches at my school and/or district.

1.3 I can choose technologies that enhance the content for a lesson.

From Harris et al. (2010), Appendix

2.1 Curriculum, goals, and technologies: To what extent technologies selected for use in the instructional plan are aligned with curriculum goals.

2.2 Instructional strategies and technologies: To what extent technology use supports instructional strategies.

2.3 Technology selection(s): To what extent technology selection(s) are appropriate, given curriculum goal(s) and instructional strategies.

2.4 “Fit”: To what extent content, instructional strategies and technology fit together within the instructional plan.

Appendix B

DIGCOMPEDU – Identified CLASSROOM-MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Addressed under teacher activities in the framework, developed by the authors

1. Professional Engagement

a) To use digital technologies to communicate orientational procedures to learners and parents, e.g. rules, appointments, events

b) To use digital technologies to inform learners and parents on an individual basis, e.g. on progress and issues of concern

2. Digital Resources

a) To select suitable digital resources for teaching and learning, considering the specific learning context and learning objective

c) To assess the usefulness of digital resources in addressing the learning objective, the competence levels of the concrete learner group as well as the pedagogic approach chosen

3. Teaching and Learning

a) To set up learning sessions, activities and interactions in a digital environment

b) To structure and manage content, collaboration and interaction in a digital environment

c) Reflect on the effectiveness and appropriateness of the digital pedagogical strategies and flexibly adjust methods and strategies

d) ….having foreseen learnersʼ needs for guidance and catering for them

e) To digitally monitor student behaviour in class and offer guidance when needed

f) Monitor and guide learners in their collaborative knowledge generation in digital environments

4. Assessment

a) To use digital assessment tools to monitor the learning process and obtain information on learnersʼ progress

b) To analyse and interpret available evidence on learnersʼ activity and progress, including the data generated by the digital technologies used

c) To use digital technologies to monitor learner progress and provide support when needed

d) To use digital technologies to enable learners and/or parents to remain updated on progress and make informed choices on future learning priorities, optional subject or future studies

5. Empowering Learners

a) To select and employ digital pedagogical strategies that respond to learnersʼ digital context, e.g. contextual constraints to their technology use (e.g. availability), competences, expectations, attitudes, misconceptions and misuses

b) To consider and respond to potential accessibility issues when selecting, modifying or creating digital resources and to provide alternatives …for special needs

6. Facilitating Learnersʼ Digital Competence

a) To be aware of behavioural norms and know-how while using digital technologies and interactions in digital environments

b) To monitor studentsʼ behaviour in digital environments in order to safeguard their well-being

c) To react immediately and effectively when learnersʼ wellbeing is threatened in digital environments (e.g. cyberbullying)

d) To identify technical problems when operating devices and using digital environments and to solve them

Appendix C

Observation form 1, translated

Observation form 1 WP6

|

Theme\time |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Classroom management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transitions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Studentsʼ exploration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Handling of noise and unrest |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adapted teaching |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Problem solving |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Observation form 2, translated

Observation form 2 WP6

|

Time |

Incident |

Reflection |

|

|

|

|

Litteraturhenvisninger

Aagaard, J., Stenalt, M. H., & Selwyn, N. (2023). ‘Out of touchʼ: University teachersʼ negative engagements with technology during COVID-19. Learning and Teaching, 16(1), 98-118. https://doi.org/10.3167/latiss.2023.160106

Allen, J. D. (1986). Classroom management: Studentsʼ perspective, goals, and strategies. American Education Research Journal, 23, 437–459. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312023003437

Bolick, C. M., & Barels, J. T. (2014). Classroom management and technology. In E. Emmer & E. J. Sabornie (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management (pp. 489-505). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203074114-34

Caniglia, J., & Meadows, M. (2018). Pre-service mathematics teachersʼ use of web resources [Article]. International Journal for Technology in Mathematics Education, 25(3), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1564/tme_v25.3.02

Carlson, T. B., & Hastie, P. A. (1997). The student-social system within sport education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 16, 176–195. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.16.2.176

Caspersen, J., Bugge, H., & Oppegaard, S. M. N. (2017). Humanister i lærerutdanningene. Valg og bruk av pensum, kompetanse og rekruttering, faglig identitet og tilknytning (HIOA-rapport 2017/2).

Cho, V., Mansfield, K. C., & Claughton, J. (2020). The past and future technology in classroom management and school discipline: A systematic review. Teaching & Teacher Education, 90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103037

Christensen, H. (2008). Utvikling av klasseledelse gjennom fag. Bedre Skole, 4.

Christensen, H., & Ulleberg, I. (2020). Klasseledelse, fag og danning, 2 utg. Gyldendal akademisk.

Dahl, T., Heggen, K., Kulbrandstad, L. I., Lavudal, T., Mausethagen, S., Qvortrup, L., Slavanes, K. G., Skagen, K., Skrøvset, S., & Thue, F. W. (2016). Om lærerrollen. Et kunnskapsgrunnlag. Fagbokforlaget.

Dicke, T., Elling, J., Schmeck, A., & Leutner, D. (2015). Reducing reality shock: The effects of classroom management skills training on beginning teachers. Teaching and teacher education, 48, 1-12. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.tate.2015.01.013

Doyle, W. (1986). Classroom organization and management. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Teaching, 3rd ed. (pp. 392–431). Macmillan.

Durak, H. Y., & Saritepecİ, M. (2017). Investigating the Effect of Technology Use in Education on Classroom Management within the Scope of the FATİH Project. Çukurova Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 46(2), 441–457. https://doi.org/10.14812/cuefd.303511

Egeberg, H., McConney, A., & Price, A. (2021). Teachersʼ views on effective classroom management: A mixed-methods investigation in Western Australian high schools. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 20, 107-124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-020-09270-w

Farkhani, Z. A., Badiei, G., & Rostami, F. (2022). Investigating the teacherʼs perceptions of classroom management and teaching self-efficacy during Covid-19 pandemic in the online EFL courses. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 7(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-022-00152-7

Feng, D., Ching Sing, C., Hyo-Jeong, S., Yangyi, Q., & Lingling, C. (2017). Examining the validity of the technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) framework for preservice chemistry teachers. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3508

Fenwick, T., Edwards, R., Sawchuk, P. (2012). Emerging Approaches to Educational ResearchTracing the Socio-Material. Routledge.

Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Hatlevik, O. E. (2018). Newly qualified teachersʼ professional digital competence: Implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1416085

Gunnars, F. (2021). A large-scale systematic review relating behaviorism to research of digital technology in primary education. Computers and Education Open, 2, 100058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2021.100058

Giæver, T., Johannesen, M., & Øgrim, L. (2020). Klasseledelse med digitale vektøy [Classroom management with digital tools] in Christensen, H. & Ulleberg, I. (eds) Klasseledelse, fag og danning [Classroom management, content and formation], Gyldendal Akademisk, 2020.

Hammerness, K. (2013). Examining features of teacher education in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research,, 57(4), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.656285

Harris, J., Grandgenett, N., & Hofer, M. J. (2010). Testing a TPACK-based technology integration assessment rubric book Chapter 6. In. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/bookchapters/6

Hastie, P. A., Sinelnikov, O. A., Brock, S. J., Sharpe, T. L., Eiler, K., & Mowling, C. (2007). Kounin Revisited: Tentative postulates for an expanded examination of classroom ecologies. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 26, 298–309. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.26.3.298

Henderson, M., Selwyn, N., & Aston, R. (2017). What works and why? Student perceptions of ‘usefulʼ digital technology in university teaching and learning. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1567–1579. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1007946

Johannesen, M., & Øgrim, L. (2020). The role of multidisciplinarity in developing teachersʼ professional digital competence. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 4(3), 72-89. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3735

Johannesen, M., Øgrim, L., & Giæver, T. H. (2014). Notion in motion: Teacherʼs digital competence. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 04, 300-312. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2014-04-05

Johannesen, M., Øgrim, L., & Hatlevik, O. E. (2019). Perspectives on teachersʼ professional digital competence. ICERI2019: 12th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Sevilla.

Johler, M., Krumsvik, R. J., Bugge, H. E., & Helgevold, N. (2022, April). Teachersʼ perceptions of their role and classroom management practices in a technology rich primary school classroom. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p. 841385). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.841385

Kimmons, R., & Hall, C. (2018). How useful are our models? Pre-service and practicing teacher evaluations of technology integration models [Article]. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 62(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-017-0227-8

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2009). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Contemporary issues in technology and teacher education, 9(1), 60–70.

Koh, J. H. L., Chai, C. S., & Tay, L. Y. (2014). TPACK-in-Action: Unpacking the contextual influences of teachersʼ construction of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK). Computers & Education, 78, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.04.022

Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Krumsvik, R. J. (2014). Klasseledelse i den digitale skolen, Cappelen Damm.

Lillejord, S., Manger, T., Nordahl, T., & Drugli, M. B. (2010). Livet i skolen. Fagbokforlaget.

Lund, A., & Aagaard, T. (2020). Digitalization of teacher education. Are we prepared for epistemic change? Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 4, 56-71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3751

McGarr, O., & McDonagh, A. (2019). Digital competence in teacher education, output 1 of the Erasmus+ funded developing student teachersʼ digital competence (DICTE) project. https://dicte.oslomet.no/

Meinokat, P., & Wagner, I. (2022). Causes, prevention, and interventions regarding classroom disruptions in digital teaching: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 27(4), 4657-4684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10795-7

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Nordahl, T. (2013). Eleven som aktør. In S. Lillejord, T. Manger, & T. Nordahl (Eds.), Livet i skolen: grunnbok i pedagogikk og elevkunnskap, 2, Lærerprofesjonalitet. Fagbokforlaget.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030. OECD education working papers.

Ogden, T. (1987). Atferdspedagogikk i teori og praksis. Universitetsforlaget.

Ozden, S. Y., Mouza, C., & Shinas, V. H. (2016). Teaching knowledge with curriculum-based technology: Development of a survey instrument for pre-service teachers. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 24(4), 471–499. http://www.learntechlib.org/p/172178

Pareto, L., & Willermark, S. (2018). TPACK in situ: A design-based approach supporting professional development in practice. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(5), 1186–1226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633118783180

Plauborg, H., Vinther Andersen, J., Ingerslev, G. H., & Fibæk Laursen, P. A. P. H. (2010). Læreren som leder. Reitzel.

Pratolo, B. W., & Solikhati, H. A. (2021). Investigating teachersʼ attitude toward digital literacy in EFL classroom. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 15(1), 97-103. https://doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v15i1.15747

Redecker, C. (2017). European framework for the digital competence of educators. DigCompEdu [PDF file] (JRC Science for Policy Report, Issue. http://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC107466/pdf_digcomedu_a4_final.pdf

Schmidt, D. A., Baran, E., Thompson, A. D., Mishra, P., Koehler, M. J., & Shin, T. S. (2009). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): The development and validation of an assessment Instrument for preservice teachers. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42(2), 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2009.10782544

Selwyn, N. (2016). Digital technology as distraction: Digital downsides: Exploring university studentsʼ negative engagements with digital technology. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(8), 1006–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1213229

Seufert, C., Oberdörfer, S., Roth, A., Grafe, S., Lugrin, J. L., & Latoschik, M. E. (2022). Classroom management competency enhancement for student teachers using a fully immersive virtual classroom. Computers & Education, 179, 104410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104410

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–31. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004

Siddiq, F., Scherer, R., & Tondeur, J. (2016). Teachersʼ emphasis on developing studentsʼ digital information and communication skills (TEDDICS): A new construct in 21st century education. Computers & Education, 92, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.006

Theelen, H., van den Beemt, A., & Brok, P. D. (2022). Enhancing authentic learning experiences in teacher education through 360-degree videos and theoretical lectures: reducing preservice teachersʼ anxiety. European journal of teacher education, 45(2), 230-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1827392

Yeh, Y.-F., Hsu, Y.-S., Wu, H.-K., Hwang, F.-K., & Lin, T.-C. (2014). Developing and validating technological pedagogical content knowledge-practical (TPACK-practical) through the Delphi survey technique. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 707–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12078