Forslag til et rammeverk for elevers akademiske perspektivtaking i samfunnskunnskap

På tvers av de ulike temaene som dekkes av samfunnsvitenskapelige fag på ungdomstrinnet og i videregående skole i nordiske land, er et hovedformål med faget å bidra til elevenes evne og tilbøyelighet til å se samfunnsmessige og politiske spørsmål, konflikter og argumenter fra ulike perspektiver.

Det å bidra til elevers evne til perspektivtaking kan ses på som et av formålene med samfunnsfag og samfunnskunnskap i skolen, nært knyttet til skolens demokratiske mandat. Tidligere litteratur har skilt mellom mellommenneskelig og akademisk perspektivtaking som begge kan spores tilbake til teorier om sosial perspektivtaking (Gehlbach et al., 2012; Sandahl, 2020). Formålet med denne artikkelen er å argumentere for og diskutere et rammeverk til bruk i arbeid med perspektivtaking i samfunnskunnskap på ungdomstrinnet og i videregående skole. Rammeverket kombinerer en eksisterende modell for perspektivtaking med perspektiver fra deliberativ og agonistisk demokratiteori for å integrere samfunnsvitenskapelige perspektiver, elevers perspektiver og perspektiver fra bredere sosiale og politiske debatter og prosesser. I presentasjonen av rammeverket argumenterer jeg for og diskuterer hvordan deliberativ og agonistisk demokratiteori kan bidra til og ha ulike implikasjoner for undervisningspraksis i skolen. Som et forslag til implikasjoner for undervisning, skisserer jeg noen muligheter og tilnærminger til det å jobbe med perspektivtaking i samfunnsfag, fokusert på hva som er det spesifikke formålet med undervisningen.

Suggesting a framework for students’ academic perspective-taking in secondary social science education

Across the various topics covered by social science subjects in secondary school in Nordic countries, one main purpose of the subject is contributing to students’ ability and inclination to see societal and political issues, conflicts and arguments from different perspectives.

Contributing to secondary students’ perspective-taking is one of the main purposes of social science education in school, closely related to the democratic mandate. Previous literature has distinguished between interpersonal and academic perspective-taking, both deriving from theories on social perspective-taking (Gehlbach et al., 2012; Sandahl, 2020). The purpose of this article is to argue for and discuss a framework for facilitating academic perspective-taking in secondary social science education. The framework combines an existing model of perspective-taking with recent deliberative and agonistic democratic theory to integrate disciplinary perspectives, students’ perspectives and perspectives from broader social and political debates and processes. In presenting the framework, I argue that and discuss how perspectives from deliberative and agonistic theory can contribute to and have different implications for social science classroom practice in secondary school. To contribute with practical implications of the article’s theoretical contributions to social science didactics research, I outline some didactic opportunities for working with perspective-taking, focusing on the specific purpose of the activity.

Introduction

Across the various topics covered by social science subjects in secondary school in Nordic countries, one main purpose of the subject is contributing to students’ ability and inclination to see societal and political issues, conflicts and arguments from different perspectives (Sandahl, 2020). Perspective-taking relates to the ability to understand our co-citizens and cooperate and coexist within a diverse and pluralistic society. As such, students’ development of perspective-taking is related to the democratic mandate of schools. Moreover, contributing to students’ perspective-taking in social science education is important for both society and the individual student when it comes to understanding and acting in society and democracy, an ever-important purpose of social science subjects in the Nordic countries (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2019; Swedish National Agency for Education, 2011). In this sense, perspective-taking may contribute to students’ opportunities to take place in society by offering them new vantage points from which to see and understand the world around them.

In his empirical intervention study in Sweden, focusing on perspective-taking as a second-order concept, Sandahl (2020) found that interventions requiring secondary students to engage with different perspectives on the good society, contributed to their understanding and perspective-taking related to different countries’ welfare models. His review of research showed that most relevant studies of students’ perspective-taking had been conducted within history education. Similarly, I argue that several studies within social science education directly or indirectly point to the need for further theoretical and empirical insight into how perspective-taking is or can be facilitated in the social science classroom for students to develop their understanding of the present-day society they are a part of (e.g., Andersson, 2018; Blennow, 2018; Mathé, 2020; Olsson, 2021). For example, Olsson (2021) found few examples of students combining individual and structural perspectives in their interpretations of current events and pointed to the challenge of designing teaching that contributes to students’ ability to identify and understand perspectives that are not explicitly addressed in the media. Another example comes from Andersson (2018), who found that certain types of teaching business economics hindered, while others facilitated, a sensitiveness to the interests of others related to sustainability issues. Finally, Blennow (2018) addressed the importance of perspective-taking related to understanding minority perspectives and the role of emotions in the social science classroom and argued that disciplinary perspectives are not sufficient when it comes to teaching contested subject matter. That is, social science education requires a sensitivity to political and affective aspects of perspective-taking, since understanding and discussing social science issues involves values, priorities and different notions about problems and their solutions. To conclude, the lack of studies dealing specifically with perspective-taking in social science education combined with the importance of perspective-taking addressed in social science didactic research, demonstrates a need to develop didactic frameworks for perspective-taking specific to social science education.

While perspective-taking is an important aspect of controversial issues discussions (Larsson, 2019), controversial issues theories are not sufficient to cover work on perspective-taking in social science education. For example, such theories often include criteria for what issues should be considered controversial (for an overview, see Sætra, 2019). I argue, however, that social science education needs a framework that can be used for a wide range of topics and issues in social science lessons, contested or not, open or closed, theoretical or practical/ongoing in society, as social science subjects include diverse themes and content (e.g., personal economy, working life, political systems, socialisation processes). Sandahl’s (2020) study made a substantial contribution to understanding students’ perspective-taking in social science education, but this phenomenon needs further theoretical development to capture different sources and types of perspectives particular to social science as a school subject. This is important, I argue, both to bring the field of social science didactics forward and to further develop how perspective-taking can be understood and addressed in secondary social science education. To contribute to this development, I combine an existing model of perspective-taking (Sandahl, 2020) with democratic theory. This combination underscores the democratic mandate social science as a school subject is imbued with (Larsson, 2019) and contributes to building a didactic framework suited for issues addressed in secondary social science education.

Building on existing literature to address the research gap identified above, the purpose of this article is to develop a didactic framework for facilitating students’ perspective-taking in social science education. As few studies explicitly address and develop perspective-taking in social science education in the Nordic context (Sandahl, 2020 is an important exception), there is a need to combine previous models of perspective-taking with theory from the social sciences, one of the knowledge domains contributing to the school subject (Christensen, 2022). I therefore incorporate deliberative and agonistic democratic theory, as these hold valuable insights for social science education both because they revolve around social scientific perspectives on society, democracy and politics and because they include the affective dimension, to develop a framework for perspective-taking in secondary social science education. The following question guides this article:

What can deliberative and agonistic democratic theory contribute to students’ perspective-taking in social science education?

This article makes a theoretical contribution to the literature on students’ perspective-taking in social science education by building on connections and opportunities that emerge in the meeting between elements of perspective-taking and deliberative and agonistic theory. The structure is as follows: I first provide an operationalisation of academic perspective-taking in social science education. Second, I briefly introduce deliberative and agonistic democratic theory and discuss their use in educational research. Third, I deduce and elaborate on four central themes and their implications for students’ perspective-taking in social science education and present a framework combining elements of perspectivetaking and democratic theory. Finally, I discuss opportunities and approaches offered by the framework that may contribute to students’ perspective-taking.

Operationalising academic perspective-taking in social science education

In this section, I draw on existing literature on perspective-taking to operationalise academic perspective-taking in social science education. For educational purposes, we can distinguish between interpersonal and academic perspective-taking, both deriving from theories on social perspective-taking developed for example in social psychology (Gehlbach et al., 2012; Sandahl, 2020). Interpersonal perspective-taking involves trying to discern other people’s “feelings, thoughts and motivations” (Sandahl, 2020, p. 2) in personal interactions. Academic perspective-taking moves beyond this as it concerns discerning others’ thoughts, feelings and motivations in relation to cultural, historical or political contexts or backgrounds. That is, it concerns the social, cultural and political phenomena and agents being studied (Sandahl, 2020, p. 5). Students’ ability and motivation to engage in interpersonal perspective-taking is an important aspect of facilitating a positive and constructive classroom climate for social scientific learning and dialogue. I focus on academic perspective-taking in this article as it includes a connection to social and political contexts that are central to social science education. However, I incorporate aspects of interpersonal perspective-taking when this is relevant for social science education (such as showing empathy in a classroom discussion).

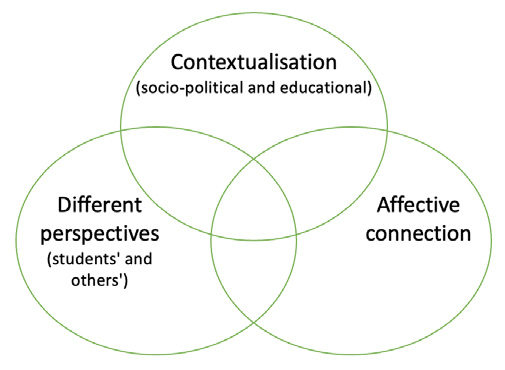

Sandahl’s (2020, p. 7) model of academic social perspective-taking, adapted from Endacott and Brooks’ (2013) model for promoting historical empathy, consists of three elements visualised in a Venn diagram. First, “contextualisation” relates to the cultural, historical and ideological setting. Second, the concept of “differential perspectives” highlights that a social issue can be considered from different points of view and that people have different opinions about them. Third, the “affective connection” underscores that social issues are value-laden and often appeal to people’s emotions in different ways. Students can react emotionally both to the issues and perspectives addressed and to each other. I build on Sandahl’s model to develop an operationalisation of academic perspective-taking for secondary social science education that incorporates the integration of disciplinary perspectives in the subject content of social science with students’ perspectives and perspectives from broader social and political debates and processes. Sandahl (2020) investigated perspective-taking as a second-order concept, focusing on disciplinary and analytic perspectives. I use his model as a starting point but develop it specifically to include the more political aspects of perspective-taking in social science education. For example, in exploring a certain social or political issue, teachers and students may draw on various social scientific perspectives (e.g., individual versus structural explanations), political lines of argument (e.g., ideological viewpoints), and their own opinions and beliefs (reflecting their socio-economic background, personal experiences etc.). This aspect of social science education implies that contextualising work with academic perspective-taking involves both socio-political and educational contexts and that the different perspectives students work with can come from students or other people or institutions and be school-internal (i.e., from students or teachers) and/or school-external (i.e., from the broader public, politics or the social sciences). The educational context includes the overall purpose of the lesson or period, the topic and content students are working with in the subject and the specific group of students involved. Using the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine (hereafter: RiU) as an example of an international conflict typically addressed in social science education (e.g., Blennow, 2018; Olsson, 2021), this could for example entail exploring European politics and Russian and Ukrainian societies (context); diverse views of the invasion, such as the different concerns of authorities, business interests, and international aid organisations as well as the views of students themselves (different perspectives); and acknowledging that students are subjected to gruesome images and constant news of war in news and social media, affecting them in different ways (affective connection). This view of academic perspective-taking is illustrated in Figure 1.

Deliberation in educational research

To frame the use of deliberative theory in this article, this section gives a brief account of the role of deliberation in educational research. As the school subject of social science in the Nordic context has a strong democratic mandate and there is a need to develop a framework directed at social scientific issues, I combine perspective-taking with democratic theory. Educational research related to education for democracy has been strongly inspired by different strands of democratic and political theory and theories of deliberative democracy. An important contribution is Habermas’ (e.g., 1995) procedural-deliberative democracy which emphasised participants’ commitment to reason, the common good and the force of the better argument. In this context, deliberation can broadly be understood as conversations aiming to solve common problems. However, the Habermasian model has been criticised. Some researchers have critiqued proceduralist models for restricting deliberation to a public sphere related to government and its institutions and strictly political issues (Benhabib, 1996). Others have criticised Habermas’ focus on rational argumentation on the grounds that it favours certain people (such as those with higher education) and excludes others from participating (Young, 1996). As a result, the development of deliberative theory has involved issues related to the matter (content) and manner (form) of deliberation and situatedness of different perspectives. Criticising deliberative democratic theory for its focus on consensus and the common good, some have argued for an agonistic model of democracy. Theorists such as Mouffe (2005) have argued that conflict is a natural and necessary aspect of modern societies and warned against ignoring political conflicts and resolving them by aiming for consensus. According to Paxton (2019), principles of agonistic democracy include political contestation, an acknowledgement that any consensus is provisional, and that conflict is seen as a productive force to unite citizens through engagement in a common process. As such, the role of conflict and consensus is central to the theoretical debate about deliberation.

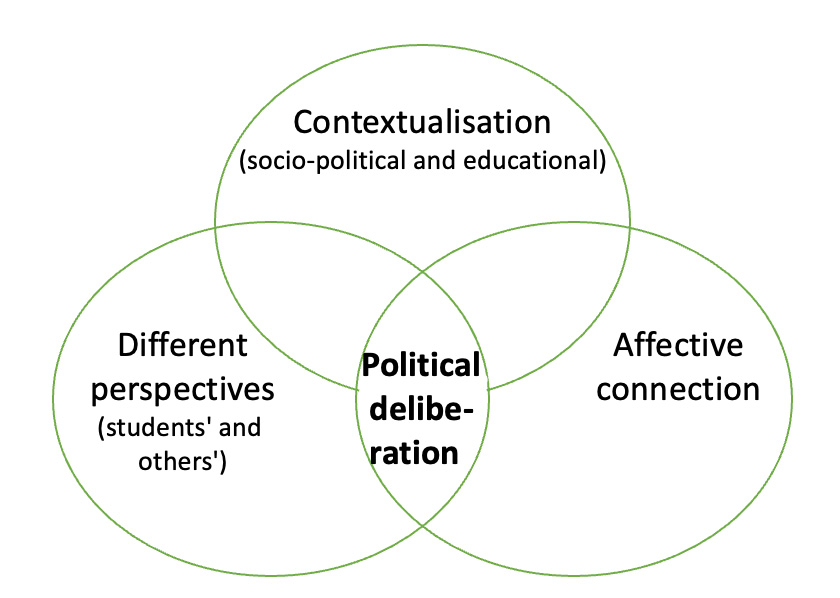

Different versions of deliberative democracy and their critics are popular theoretical perspectives when it comes to understanding issues such as classroom discussion (e.g., Ruitenberg, 2009; Samuelsson, 2016; Samuelsson & Ness, 2019; Tryggvason, 2018). While previous studies have found that classroom discussion can be beneficial both for students’ knowledge and for thir engagement (Hess & McAvoy, 2015; Swedish Institute for Educational Research, 2022), some critics have argued that deliberation and deliberative democracy have been used in a variety of ways across theoretical and empirical research and that tenets of democratic theory have been transferred uncritically into educational research (Reich, 2007; Samuelsson, 2016; Samuelsson & Bøyum, 2015). Related to their critique, Samuelsson and Bøyum (2015) and Reich (2007) have suggested that a stronger integration between democratic and educational research is needed. This article contributes to such integration by examining how ideas from recent deliberative and agonistic democratic theory, particularly related to different forms of deliberation, might contribute to students’ perspective-taking in social science education. To achieve this, I use democratic theory as a lens through which to shed light on key aspects of perspective-taking in social science education. For the purpose of this article and to include different kinds of classroom conversations, I view deliberative and agonistic accounts of democracy to fall somewhere on a spectrum, with the promotion of rational consensus on one end and continual disruption on the other (Paxton, 2019). Consequently, while not attempting to assimilate deliberation and agonism (Tryggvason, 2018), I adopt a rather broad use of the term deliberation, also including agonistic forms of political communication not aiming for consensus. Specifically, I focus on how different forms and aspects of political deliberation (i.e., relating to socio-political issues) can contribute to students’ perspective-taking in social science education. Figure 2 illustrates the combination of political deliberation and the three components of academic perspective-taking.

In Figure 2, political deliberation is placed in the middle of the Venn diagram, overlapping with the three elements from Sandahl (2020). I argue that contextualisation, different perspectives and the affective connection can be fruitfully addressed through different forms of classroom deliberation. I use the concept of political deliberation broadly to include different forms of classroom conversation or discussion, not only those adhering to specific deliberative criteria and intended for decision-making. Examples include whole class or group discussions, prepared debates, and many less structured conversation formats, which may serve different purposes and allow students to engage with multiple perspectives from a range of sources. They can be seen as political both in content and form: social science issues often concern values, priorities and different possible solutions to socio-political problems, and students may have different opinions and beliefs about them. For example, turning again to the RiU, deliberation can be used to address complex issues, such as investigating the underlying causes of the invasion (contextualisation) and analysing political communication from involved or affected actors (different perspectives), as well as processing students’ reactions (affective connection). There is a potential, I argue, that through classroom deliberation of relevant issues, students can develop their knowledge and understanding of social science subject content as well as get help dealing with a dramatic situation. However, various forms of deliberation have different and important implications for academic perspective-taking in social science education, which I elaborate in the following.

A framework for academic perspective-taking drawing on deliberative and agonistic theory

In the brief account of deliberative and agonistic accounts of democracy above, four central themes emerged as important in the theoretical debate which are also relevant for students’ perspective-taking in social science education: (1) the matter of deliberation, (2) situatedness of perspectives, (3) the manner of deliberation, and (4) the role of conflict and consensus in deliberations. In the following, in order to develop a framework for perspective-taking in social science education, I elaborate different approaches to the four themes based on deliberative and agonistic theory.

The matter of deliberation

In this paragraph, I discuss the role of the matter of deliberation for students’ perspective-taking. The matter or object of deliberation concerns on what topic or issue students are to be able to see different perspectives. Broadly, this means social scientific topics like the economy, the relationship between individuals and society, and the rule of law. The object of deliberation is also influenced by current events and other issues of interest to teachers and students in the classroom, of which the RiU is a pertinent example. Because discussions can be spontaneous, teachers and students are often required to discuss issues they were not prepared to discuss that might provoke disagreement and discomfort. Due to the potential negative consequences of discussing contested normative issues, the matter of deliberation is a recurring theme in democratic theory. Benhabib (1996), for example, clearly stated that conversational restraint is a limitation, meaning that no topic is off limits. In her line of thought, conversational restraint risks foreclosing deliberation about important public issues (Enslin et al., 2001, p. 122). Similarly, Young argued that as there are differences and conflicts in diverse societies, the object of deliberation will be contested. That is, given that a society has difficult, normative disagreements or conflicts, these should not be kept out of public deliberations, as public deliberation may, according to theorists such as Benhabib (1996) and Young (1996), be our best hope for coming to some kind of resolution. In this article, the central point is that different kinds of issues are suitable for different purposes when it comes to students seeing or understanding such issues from the perspective of someone differently situated than themselves.

Situatedness of perspectives

Situatedness concerns students’ and others’ context and personal situation, that is, aspects of our lives that shape how we view the world around us. In this paragraph, I therefore discuss the role of situatedness for students’ perspective-taking in social science education. Young is known for her work on inclusion of minority groups in democratic deliberations, an essential aspect of which is viewing difference as a resource for reaching understanding among people with different cultural backgrounds, thereby increasing people’s opportunity and ability to engage with the perspectives of others. The situatedness of perspectives thereby includes understanding the context of others’ perspectives. The social science classroom is an important arena for students to discover, understand and express perspectives on socio-political issues, both students’ own and from other sources. When it comes to the situatedness of perspectives, the role of young people as democratic participants is also important for social science education. Young (1996, 2002) and Benhabib (1996) shared the notion that those affected by a democratic decision should be included in the process of deliberation and decision-making, for example people across political boundaries. The question of whose perspectives are considered legitimate in political deliberation is also pertinent in an educational context, as students are involved in discussing a range of relevant issues impacting their present and future lives. Students under the legal voting age have access to several forms of participation and even engagement within the youth wings of political parties, but they are often excluded from voting in and running for election. Students may also have experienced that their perspectives are not taken seriously, for example in public debate about political issues. Young’s bid to widen access to deliberation is therefore relevant in an educational context. In the classroom, secondary students are in principle considered legitimate participants with equal political status. Students are positioned as actors who are asked to reflect, interpret and discuss independently and critically, which enables academic perspective-taking and considerations of the situatedness of perspectives. Moreover, a central reason why perspective-taking is important in social science education, is that it widens students’ horizons and allows them to understand and consider political issues from different angles, which again may influence their political choices and actions.

The manner of deliberation

In this paragraph, I discuss different approaches to the manner of deliberation. Manner broadly concerns how deliberations are organised and carried out, including which norms, rights and restrictions guide them and their participants. The scholarly debate about the manner of deliberation has developed substantially since Habermas’ procedural-deliberative democratic theory, in tandem with increasing heterogeneity in Western democracies. To include women and cultural minorities and to allow participants to learn from others’ experiences and social perspectives, Young (1996) suggested three alternative forms of communication to supplement critical argument. Greeting involves introductory phrases that are often necessary to establish trust or respect, such as mild flattery. Rhetoric refers to the forms and styles of speaking that attend to the audience, for example, by addressing their situatedness or context as well as efforts to get and keep attention. Storytelling fosters understanding across differences through activities such as revealing people’s particular experiences that cannot be shared by others and illuminating one’s sources of values, culture and meaning.

Benhabib (1996, pp. 82–83), however, argued that Young’s alternative forms of communication are good examples of everyday communication that should not necessarily be included in specifically political communication. Rather than opening the specific forms of communication included in political deliberation, Benhabib emphasised how public deliberation within and across nation-state boundaries contributes to transforming meaning through “democratic iterations” (Benhabib, 2007, p. 447). Democratic iterations are processes of deliberation and learning through which universalist right claims are contested and contextualised. Every iteration transforms meaning, adds to it and enriches it. For example, the distinctions between “citizens” and “non-citizens”, “us” and “them”, can be negotiated through democratic iterations (Benhabib, 2007).

As several studies have highlighted discussions as an important citizenship activity for students (e.g., Hess & McAvoy, 2015; Mathé, 2018), the manner of deliberation is an important issue. Fortunately, a variety of communication forms can be used in the classroom. It seems key, however, that teachers are aware of the difference between focusing on rational argument and focusing on alternative forms of communication (and the issues and knowledge and skills suitable for each of them). Choosing one or the other should ultimately relate to the purpose of the activity. For example, the teacher must consider whether the purpose is for students to practice forming logical arguments and responding to opposing ones about a specific issue or for students to understand the perspectives of others without necessarily agreeing with or challenging these. That is, the manner of deliberation relates to the kind of perspective-taking that is encouraged. This question of the manner of deliberation relates closely to another contested issue highly relevant for the social science classroom, namely the role of conflict and consensus in political deliberations, which I discuss below.

The role of conflict and consensus in deliberation

I now turn to the last of the four aspects of political deliberation relevant for students’ perspective-taking in social science education that I address in this article. Whether or not to strive for consensus is an important question for teachers and students planning and engaging in classroom discussions. Following the Habermasian model of deliberative democracy, aiming for consensus is an essential characteristic of deliberation, especially of deliberation as decision-making (Habermas, 1995). Recently, researchers have debated, nuanced and even rejected the aim, or requirement, of consensus (e.g., Leiviskä & Pyy, 2021; Mouffe, 2005; Paxton, 2019; Ruitenberg, 2009; Samuelsson, 2018). A critique of deliberative theories of democracy is that they ignore fundamental conflicts and power relations in society. According to Paxton (2019), a “danger with consensus is its frequent desire to label shared principles as neutral, rational or even universal” (p. 4). Mouffe (2005) claimed that true consensus is not realistic and that claims of consensus necessarily suppress or silence dissenting perspectives.

For this article, the question is why and how conflict and consensus matter for students’ academic perspective-taking in social science education. Questions arise, such as: Does striving for consensus enable or inhibit students’ perspective-taking? Can an agonistic approach exacerbate or even initiate conflict among peers, also beyond the political, perhaps weakening students’ inclination to be open to perspectives other than their own? In response to the first question, Leiviskä and Pyy (2021), drawing on Martha Nussbaum (2013), have argued that the political project in citizenship education should be to strive towards common goals rather than encouraging conflict. Their idea is that finding common solutions motivates us to try to understand where others are coming from and how and why they might see things differently than we do, which is arguably also relevant for academic perspective-taking in social science education.

Conversely, teachers in Samuelsson’s (2018) study described how, in their experience, aiming for consensus inhibited students’ free discussion. Offering alternative ways of conceptualising and actualising consensus, Samuelsson (2018) presented a multifaceted concept of consensus that allows for agreement and disagreement among students on issues such as the procedures for reaching a decision, facts pertaining to the issue under discussion, and the outcome itself. In this view, consensus is a “regulative idea” (Samuelsson, 2018, p. 2) to guide the discussion rather than a required endpoint. For a classroom discussion on students’ own opinions or on differing political or scientific solutions to a societal problem (cf. Sandahl, 2020), applying consensus as a regulative idea might mean that students are encouraged to listen actively to each other, build on each other’s arguments and try to find some common ground. This may contribute to perspective-taking as students are required to relate actively to others’ points of view. Contrary to the consensus approach, Mårdh and Tryggvason (2017) argued that, to inspire students’ political engagement, we need to understand that political identification always requires a “constitutive outside” (Mouffe, 2005, p. 15) or some feeling of group belonging, resulting in a sense of a them outside of one’s own group. Ignoring this affective aspect of political identification might result in increased political apathy (Mårdh & Tryggvason, 2017). However, Leiviskä and Pyy (2021) cautioned against exposing children and young students to the notion of political conflict in the classroom. They argued that it may be hard for students to distinguish between disagreements on issues and conflicts between themselves and fellow students. The risk is that conflicts are reinforced, and that the socio-emotional classroom environment suffers. An implication of this view is that a conflict-approach may hinder perspective-taking if it leads to a poorer and more polarised classroom climate. This discussion shows that deliberative and agonistic ideas have different implications for classroom discussions meant to contribute to students’ perspective-taking in social science education. Consequently, different approaches may be used for different types or purposes of perspective-taking, such as understanding an issue from different ideological perspectives or from someone with a different background than oneself, which a framework for academic perspective-taking needs to open for.

Summarising key connections: A framework for academic perspective-taking through political deliberation

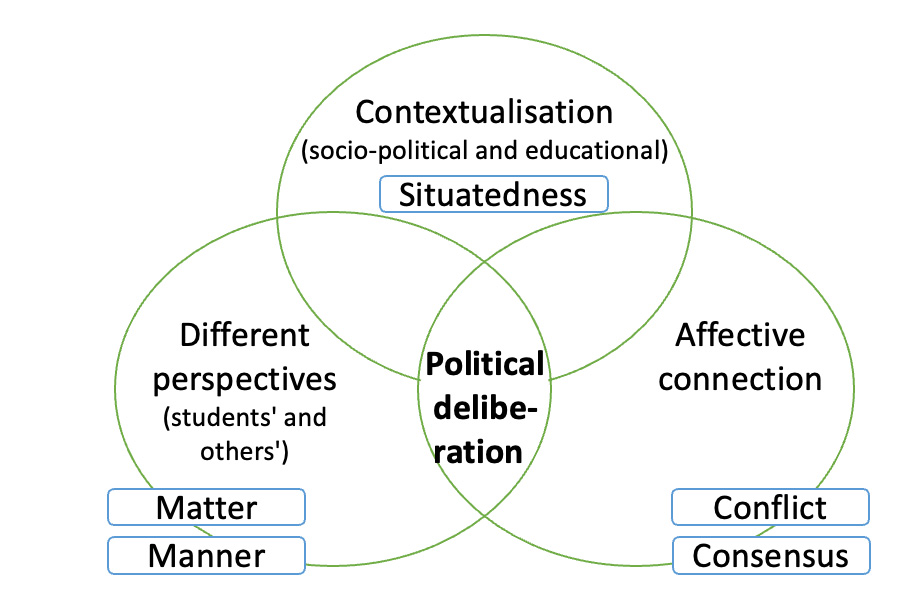

In the previous section, I argued for the relevance of deliberative and agonistic perspectives in relation to academic perspective-taking in social science education. Figure 3 illustrates the connections identified through the discussion above and can be seen as a framework for working with academic perspective-taking in secondary social science education.

To capture different sources and types of perspectives particular to social science education, the framework illustrated in Figure 3 combines the three elements of academic perspective-taking with four important aspects of deliberative and agonistic theory. I argue that the democratic theory applied here contributes to academic perspective-taking in social science education in secondary school, as the resulting framework accommodates the diverse kinds of perspectives and their sources – both subjective and disciplinary – that are necessary in this school subject.

To exemplify: Teaching about the RiU may require contextualisation on Russian and Ukrainian societies and how they differ from students’ own (situatedness). The invasion can be related to a range of social science themes – such as political systems, war and conflict, international relations, and foreign aid – and perspectives on these (matter). The form of deliberation should be suited to the purpose of the lesson (manner). Students’ affective connection relates to the level of agreement in the classroom, either on procedures for the conversation or the subject matter itself (conflict and consensus), as well as the role of students’ emotional reactions to the topic. In the following section, I qualify the model of academic perspective-taking in secondary social science education that combines and integrates deliberative and agonistic ideas.

Discussion and implications

To answer this article’s guiding question, I build on the connections identified above and illustrated in Figure 3 to discuss what opportunities emerge when relating aspects of deliberative and agonistic theory to the three elements of academic perspective-taking: contextualisation, different perspectives and affective connection. The purpose of this section is to argue for some opportunities and approaches offered by the framework that can be used in social science education when focusing on students’ perspective-taking. While this article centres around the student as the actor of perspective-taking, teachers are essential in facilitating and qualifying this work in the classroom. In the following, implications for practice are consequently directed at social science teachers.

Contextualisation: The situatedness of students and the other

Contextualisation is an element of academic perspective-taking that speaks to the importance of framing perspective-taking activities in a socio-political and educational context. While the socio-political context involves students’ communities and the social and political climate, the educational context involves considering the overall purpose of the lesson or period, the content students are working with in the subject and the specific group of students involved. Moreover, both types are relevant for contextualising the perspectives of others. Building on Sandahl’s (2020) findings, taking into account both the context of the students in the classroom as well as other relevant contexts, such as those being studied, could be important to facilitate perspective-taking. In terms of students’ own context, this could entail characteristics of their everyday lives and local community, as well as the national socio-political context. It also includes secondary students’ political status, such as whether or not they are national citizens, have the right to vote in elections, and to which extent they are considered already citizens – as opposed to future or not-yet citizens (Biesta, 2011).

For students’ perspective-taking, their own situatedness is important in at least two ways. First, understanding one’s own context and position, and how it may differ from other contexts, can contribute to qualifying questions, arguments, and deliberation. Second, it has implications for the ways in which students can act on their convictions or interests, whether they are based on their own perspectives or interests or in support of others’. For example, learning about the conditions of children fleeing from war, or pets left behind, can inspire students to want to help. The channels of participation available to them necessarily influence their potential actions. For teachers, this situation might imply shifting the focus from political individualism directed at voting as the main act of political participation to opportunities for students’ individual and collective engagement and mobilisation, within and outside the formal structures of representative democracy. Such a shift can be implemented in social science by activities such as allowing students to engage in serious political deliberation and other actions directed at real problems that students perceive to be relevant and to get involved in local, national or global issues by using the means available to them.

The context of other perspectives, whether they stem from specific people or institutions, can be seen as a part of the subject matter, for example when asking: In what social, economic and political context are the perspectives of the other situated? As such, context relates to the matter of deliberation addressed in the following section.

Different perspectives: The matter and manner of perspective-taking

A key question for teachers when facilitating students’ perspective-taking is what kind of topic or issue is suitable for the specific purpose of the lesson and what kinds of perspectives (and from what sources) they intend the students to understand or work with. As outlined previously, sources can arise from various social scientific perspectives (e.g., individual versus structural explanations), political lines of argument (e.g., ideological viewpoints), and students’ own opinions and beliefs or those of others (e.g., those available through interviews and in fiction). In this sense, the matter of the perspective-taking activities includes both the subject-specific topic and the kinds of perspectives explored. Social science education offers a plethora of issues to choose from, and they can often easily be related to the current news cycle or issues that interest students. Following Benhabib (1996), Young (1996) and Mouffe (2005), issues such as environmental challenges, immigration and integration need to be discussed openly for people to come to workable solutions, to understand (if not agree with) others’ perspectives and values, and to allow the conflictual to be channelled into political discussions about adversarial political projects rather than into isolation, anger and violence. As such, the matter is also related to the manner, or form, of the activity.

Classroom conversations or discussions might work like what Benhabib (2004) referred to as democratic iterations. Alternatively, perhaps they can be considered micro-iterations that contribute to the broader iterative processes in society described by Benhabib. In other words, by repeating, supporting and questioning existing norms, challenging the status quo or worrying about the future, students are in a position to negotiate current understandings. In this way, they not only express their own understandings, but also allow them to be altered and challenged. Moreover, by participating in such discussions, students may influence others and, consequently, create change. Awareness of the potential of democratic iterations may be a way of negotiating different perspectives, allowing them to meet, be reflected on and developed. As a mandatory school subject, social science is in a unique position to contribute to such awareness.

Enslin (2006) posited that Young’s idea of reaching understanding across differences can be implemented in schools in a range of curricular activities. In social science, we can draw on Young to develop a form of storytelling, in which particular experiences and the source of our values are brought into the conversation to further what she called a “collective social wisdom” (Young, 1996, p. 132) not available from any one perspective alone. Indeed, from such narratives, different perspectives on issues such as identity and socialisation, economic inequality and foreign aid might emerge. This way of engaging with “others” might make it easier for students to develop solidarity by giving them increased insights into the experiences and lives of people who are situated differently from themselves. Enslin (2006) noted that even these forms of communication may be subject to critical evaluation, for example, by asking, “Is this discourse respectful, publicly assertable, and does it stand up to public challenge?” (Enslin, 2006, p. 60). In social science education, these activities can be combined with content knowledge to promote not only student understanding of how current systems and structures create differences, but also the potential of changing these systems (Mouffe, 2005, 2013). Such understanding relates to skills such as argumentation, justifying opinions and weighing evidence, which are emphasised in social science education in the Scandinavian countries (e.g., Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2019; Swedish National Agency for Education, 2011). Moreover, both Benhabib (1996) and Young (1996) emphasised the importance of listening to others.

However, Mouffe might interject that no discourse is free from power. As a result, teachers must strive to organise deliberation in a way that makes it possible to challenge existing power relations. Nonetheless, it is easy to envision a classroom situation where some students’ stories are more willingly listened to and appear more interesting, important and competent than others’. Such an imbalance might stem from the student’s popularity, richness of experience related to the issue at hand, precise use of social scientific concepts, or the way they tell their story. That is, the way various perspectives are presented in the classroom matters for students’ ability and inclination to engage with them.

Affective connection: Supporting or inhibiting perspective-taking through conflict

In any classroom discussion, whether it takes the form of an exploration of ideological perspectives or students’ own opinions, the teacher facilitating the discussion will have the opportunity to allow, dig into or even emphasise disagreements and decide whether or not to aim for some kind of consensus or mutual solution. For the purpose of this article, an important question is whether disagreements can support students’ perspective-taking, as they may allow students to listen to and understand the perspectives of their peers, or whether conflictual aspects of a discussion might instead hinder perspective-taking because students then focus on defending their own views rather than exploring others’.

Young people have reported that facing opposition, in the form of stronger arguments or a harsh debating climate, is uncomfortable (Ekström & Shehata, 2016; Mathé, 2018). This may also be the case in the classroom in situations where students discuss issues about which they disagree. Drawing on Mouffe’s (2005, 2013) concept of political adversaries might be useful here. Mouffe argued that, as human societies are naturally conflictual, coming to agreement on substantive political issues is not realistic or desirable. Accepting that the goal of the discussion or debate is not necessarily to “win” the argument but to engage with other perspectives or to challenge existing power relations might make it easier for young people to dare to participate in discussions of complex issues. I would like to note, however, that such a feat is not easily accomplished by social science education alone. As Young (2002) has highlighted, engaging in heated discussions seems particularly challenging for people with marginalised experiences (Törnegren, 2013). Young may have a point that debate-like formats, which students may encounter both within and outside the classroom, especially in social media, favour assertive and aggressive speaking styles; moreover, it also seems that some groups are at particular risk of harassment. As such, conflict may be an obstacle for fruitful perspective-taking. Conversely, perhaps it is precisely the perspectives of those with whom we disagree that we should attempt to understand.

In the social science classroom, the goal should not be for students to necessarily adopt or even accept others’ perspectives, but rather to understand them. The question is: Where does this leave the teacher tasked to facilitate discussions and moderate the level of conflict (or, in some cases, try to inspire an exploration of different perspectives despite seeming consensus among the students)? Given the different characteristics and potential benefits of the various forms of deliberation, one solution is to let the educational purpose decide. Procedural forms of deliberation may be suited when the purpose is for students to practice formulating and listening to rational arguments to find a solution to a common problem (Habermas, 1995). Here, students become acquainted with pro et contra arguments regarding a specific issue. Communicative forms of deliberation may be suited when the purpose is for students to understand how and why their peers (or others) think differently than they do concerning societal issues (Young, 1996). In such instances, the focus is not on argumentation but on allowing personal narratives to illustrate how we are all shaped by our experiences and positionalities. Finally, agonistic forms of deliberation or discussion may be suitable when the purpose is to expose students to different viewpoints (each other’s or from other sources) so they can practice facing and responding to opposing perspectives (Paxton, 2019). During this process, the teacher’s role is particularly important. For example, the teacher may want to involve students in developing some ground rules for discussion (e.g., opposing arguments instead of each other, hearing each other out, building on others’ input before responding). However, it is important to note that the purpose of the framework is to open for several opportunities for and approaches to academic perspective-taking, depending on the purpose of the lesson, not to be prescriptive for classroom practice.

Concluding remarks

The purpose of this article has been to develop a framework for academic perspective-taking in social science education by discussing what deliberative and agonistic democratic theory can contribute to students’ perspective-taking in social science education and, by extension, argue for the potential role and function of this integrated framework for secondary students. As such, this article contributes to the research literature by building on connections and opportunities that emerge in the meeting between elements of perspective-taking and deliberative and agonistic theory to develop academic perspective-taking theoretically. Specifically, as the framework places students’ political deliberations in the centre of academic perspective-taking, the students’ meeting with the subject is in the foreground. Through such exploration of social science questions and issues, the three elements of academic perspective-taking can be included to support secondary students’ perspective-taking opportunities and experiences in the classroom.

While this article aims at making a theoretical contribution to the literature on students’ perspective-taking in social science education, the suggested framework can be further developed: other theoretical perspectives might challenge or add to the suggested connections and it may be adapted to suit specific thematic areas of the school subject such as those addressed in previous studies (e.g., Andersson, 2018; Blennow, 2018; Olsson, 2021). Moreover, empirical research is needed to answer several remaining questions. For example, what does it look like when teachers facilitate perspective-taking activities in their lessons? What kinds of perspectives are in focus, and how are students asked to relate to these? Future research may build on the theoretical framework developed in this article to advance empirically based knowledge about perspective-taking as a central aspect of social science education.

To conclude, aspects of deliberative and agonistic theory offer several approaches that may contribute to students’ perspective-taking in social science education. For example, when working with the three elements of academic perspective-taking (i.e., contextualisation, different perspectives and affective connection), teachers can consider the situatedness of perspectives, the matter and manner of deliberation, and the role of conflict and consensus. Importantly, what approach is fruitful depends on the specific purpose of the lesson or activity. As such, teachers may consider what kind of perspective-taking they wish to focus on and what kind of deliberation or discussion is suitable for this purpose. By qualifying work with perspective-taking through political deliberations in the classroom, this framework may contribute to students’ opportunities to gain new vantage points from which to see, understand and influence the world around them. This is important not only for individual students in an educational context, but also for the resilience of a democratic society.

Litteraturhenvisninger

Andersson, P. (2018). Talking about Sustainability Issues when Teaching Business Economics – The ‘Positioning’ of a Responsible Business Person in Classroom Practice. Journal of Social Science Education, 17(3), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.4119/jsse-885

Benhabib, S. (Ed.) (1996). Democracy and difference: Contesting the boundaries of the political. Princeton University Press.

Benhabib, S. (2004). The rights of others: Aliens, residents, and citizens (Vol. 5). Cambridge University Press.

Benhabib, S. (2007). Democratic Exclusions and Democratic Iterations: Dilemmas of ‘Just Membership’ and Prospects of Cosmopolitan Federalism. European Journal of Political Theory, 6(4), 445–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885107080650

Biesta, G. (2011). Learning democracy in school and society: Education, lifelong learning, and the politics of citizenship. Sense.

Blennow, K. (2018). Leyla and Mahmood – Emotions in Social Science Education. Journal of Social Science Education, 17(1), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.4119/jsse-867

Christensen, T. S. (2022). Observing and interpreting quality in social science teaching. Journal of Social Science Education, 21(2). https://doi.org/10.11576/jsse-4147

Ekström, M., & Shehata, A. (2018). Social media, porous boundaries, and the development of online political engagement among young citizens. New Media & Society, 20(2), 740– 759. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816670325

Endacott, J., & Brooks, S. (2013). An updated theoretical and practical model for promoting historical empathy. Social Studies Research and Practice, 8(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/SSRP-01-2013-B0003

Enslin, P. (2006). Democracy, social justice and education: Feminist strategies in a globalising world. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 38(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2006.00174.x

Enslin, P., Pendlebury, S., & Tjiattas, M. (2001). Deliberative democracy, diversity and the challenges of citizenship education. Journal of philosophy of education, 35(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.00213

Gehlbach, H., Brinkworth, M. E., & Wang, M.-T. (2012). The social perspective taking process: What motivates individuals to take another’s perspective? Teachers College Record, 114(1), 197–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811211400108

Habermas, J. (1995). Tre normative demokratimodeller [Three normative models of democracy]. In E. O. Eriksen (Ed.), Deliberativ politikk: Demokrati i teori og praksis [Deliberative politics: Democracy in theory and practice] (pp. 30–45). Tano.

Hess, D., & McAvoy, P. (2015). The political classroom. Evidence and ethics in democratic education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Larsson, A. (2019). Kontroversiella samhällsfrågor i samhällsorienterande ämnen 1962–2017: en komparation [Controversial societal issues in social studies 1962–2017: a comparison]. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, (3), 1–23. https://journals.lub.lu.se/nordidactica/article/view/21878/19690

Leiviskä, A., & Pyy, I. (2021). The Unproductiveness of Political Conflict in Education: A Nussbaumian Alternative to Agonistic Citizenship Education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 55(4–5), 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12512

Mathé, N. E. H. (2018). Engagement, passivity and detachment: 16-year-old students’ conceptions of politics and the relationship between people and politics. British Educational Research Journal, 44(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3313

Mathé, N. E. H. (2020). Preparing to Teach Democracy: Student Teachers’ Perceptions of the ‘Democracy Cake’ as a Set of Teaching Materials in Social Science Education. Journal of Social Science Education, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.4119/jsse-1243

Mouffe, C. (2005). The return of the political (Vol. 8). Verso.

Mouffe, C. (2013). Agonistics: Thinking the world politically. Verso.

Mårdh, A., & Tryggvason, Á. (2017). Democratic education in the mode of populism. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 36(6), 601–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-017-9564-5

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2019). Relevance and central values. https://www.udir.no/lk20/sak01-01/om-faget/fagets-relevans-og-verdier?lang=eng

Nussbaum, M. (2013). Political emotions: why love matters for justice. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Olsson, R. (2021). Samhälle och individ – En undersökning i samhällskunskapsdidaktik om elevers förståelse av nyhetshändelser [Society and individual – An investigation in social science education about students’ understanding of news events]. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 11(2), 57–86. https://journals.lub.lu.se/nordidactica/article/view/23169/20866

Paxton, M. (2019). Agonistic democracy: rethinking political institutions in pluralist times. Routledge.

Reich, W. (2007). Deliberative democracy in the classroom: A sociological view. Educational Theory, 57(2), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2007.00251.x

Ruitenberg, C. W. (2009). Educating political adversaries: Chantal Mouffe and radical democratic citizenship education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 28(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-008-9122-2

Samuelsson, M. (2016). Education for deliberative democracy: A typology of classroom discussions. Democracy & Education, 24(1), Art. 5. https://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol24/iss1/5

Samuelsson, M. (2018). Education for deliberative democracy and the aim of consensus. Democracy & Education, 26(1), Art. 2. https://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol26/iss1/2

Samuelsson, M., & Bøyum, S. (2015). Education for deliberative democracy: Mapping the field. Utbildning & Demokrati, 24(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.48059/uod.v24i1.1031

Samuelsson, M., & Ness, I. J. (2019). Apophatic listening (A response to Deliberating public policy issues with adolescents: Classroom dynamics and sociocultural considerations). Democracy & Education, 27(1). https://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol27/iss1/6

Sandahl, J. (2020). Opening up the echo chamber: Perspective taking in social science education. Acta Didactica Norden, 14(4), Art. 6. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.8350

Swedish Institute for Educational Research (2022). Att lära demokrati – lärares arbetssätt i fokus. Systematisk forskningssammanställning 2022:3 [Learning democracy – focusing on teachers’practices. Systematic review 2022:3] Skolforskningsinstitutet. https://www.skolfi.se/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Att-lara-demokrati.pdf

Swedish National Agency for Education (2011). Social studies. Stockholm: Skolverket. https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.4fc05a3f164131a74181078/1535372299998/Soci al-studies-swedish-school.pdf

Sætra, E. (2019). Teaching controversial issues: A pragmatic view of the criterion debate. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 53(2), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467- 9752.12361

Törnegren, G. (2013). Utmaningen från andra berättelser: En studie om moraliskt omdöme, utvidgat tänkande och kritiskt reflekterande berättelser i dialogbaserad feministisk etik [The Challenge from Other Stories: A Study on Moral Judgment, Enlarged Thought and Critically Reflecting Stories in Dialogue Based Feminist Ethics]. Doctoral dissertation, Uppsala University. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:677029/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Tryggvason, Á. (2018). Democratic education and agonism: Exploring the critique from deliberative theory. Democracy & Education, 26(1), Art. 1. https://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol26/iss1/1

Young, I. M. (1996). Communication and the other: Beyond deliberative democracy. In S. Benhabib (Ed.), Democracy and difference: Contesting the boundaries of the political (pp. 120–135). Princeton University Press.

Young, I. M. (2002). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford University Press.