Foreldreveiledning i trygghetssirkelen: En systematisk gjennomgang av effektivitet ved bruk av foreldreveiledningsprogrammer for familier med sammensatte problemer

Foreldreveiledning i trygghetssirkelen (på engelsk Circle of Security) er et forenklet, relasjonsbasert program med den hensikt å utvikle foreldrenes observasjon og evne til å foreta slutninger knyttet til det å forstå barnets behov, øke følsomheten overfor eget barn, hjelpe til med følelsesmessig regulering samt å redusere negative egenskaper som man tillegger barnet.

Foreldreveiledning i trygghetssirkelen (på engelsk Circle of Security, COS-p) er et forenklet, relasjonsbasert program med den hensikt å utvikle foreldrenes observasjon og evne til å foreta slutninger knyttet til det å forstå barnets behov, øke følsomheten overfor eget barn, hjelpe til med følelsesmessig regulering samt å redusere negative egenskaper som man tillegger barnet. COS-p er et mye brukt foreldreprogram som har oppnådd popularitet over hele verden. Til tross for at det er et av de mest brukte tiltakene innen norske barneverntjenester, har det ikke blitt gjort forskning på effektiviteten av programmet i barnevernsammenheng. Denne studien tar derfor sikte på å etablere en systematisk oversikt over programmets effektivitet for familier innenfor barnevernsystemet, både når det gjelder omsorgspersoner og til fordel for barna.

Circle of Security-Parenting: A Systematic Review of Effectiveness When Using the Parent Training Programme with Multi-Problem Families

This study aims to establish a systematic overview of the Circle of Security-parenting programme’s effectiveness for families within the child protective services system, regarding both caregivers and benefits for the children.

Circle of Security-parenting (COS-p) is a simplified, relationship-based programme with the intention of developing parents’ observation and inferential skills related to understanding their child’s needs, increasing sensitivity to their child, aiding in emotional regulation, as well as decreasing any of their negative attributions to their child. COS-p is a widely used parenting programme that is gaining global popularity, as it is currently being delivered across several continents. Despite being one of the most frequently used interventions in Norwegian child protective services (CPS), no research has been conducted on this programme’s effectiveness when used in the CPS context. This study therefore aims to establish a systematic overview of the programme’s effectiveness for families within the CPS system, regarding both caregivers and benefits for the children.

Introduction

Circle of Security-parenting (COS-p; Cooper et al., 2009) is a widely used programme that is gaining global popularity. It is currently being delivered across several continents, and most Nordic countries have implemented it as part of their early intervention foundation (EIF Guidebook, 2019; Plauborg & Jacobsen, 2017). However, empirical support for COS-p is still limited (Mothander et al., 2018). Since 2010, more than 2000 persons in Norway, with competencies as psychologists, social workers, school nurses and child welfare workers, have been trained to use the COS-p training method as part of their daily work with at-risk families (Bråten & Sønsterudbråten, 2016). Here, an at-risk family refers to one with known risk factors related to family characteristics or connected with the child’s environment, but the family appears unaffected in daily life.

Additionally, COS-p is listed as one of the most frequently used interventions in Norwegian child protective services (CPS) (Christiansen et al., 2015). However, no research has been conducted on this intervention’s effectiveness when used in the CPS context. In contrast to at-risk families, most of those involved with CPS are multi-problem families that display multiple risk factors concerning the children’s welfare and wellbeing. This review therefore focuses on identifying studies where COS-p is used as a training intervention for parents from multi-problem families. The aim is to establish a systematic overview of the COS-p programme’s effectiveness for those living in multi-problem families, with respect to both caregivers and benefits for the children. The research question is what change in effectiveness multi-problem families can expect from participating in the COS-p programme.

Circle of Security-parenting

COS-p is a simplified, relationship-based parenting programme originating from a far more comprehensive parental guidance programme, Circle of Security (COS). COS is available in two versions: COS Virginia and COS International. COS Virginia consists of an individual treatment model and a group model, whereas COS International comprises a treatment method (COS Intervention) and a parent training method (COS-p; Cooper et al., 2009). The research on the effectiveness of COS Intervention forms the basis of the development of COS-p, where findings from studies of COS Intervention have been applied to promote the possible effectiveness of COS-p. However, while COS-p shares the same theoretical framework and some resources, its model of implementation is very different, and so is any evidence of its effectiveness. Summarised, COS Intervention contains five elements: (1) Conduct and videotape a pre-group assessment using the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) and the Circle of Security Interview (COSI). (2) Review and analyse SSP and COSI to create a treatment plan. (3) Evaluate each group member’s core sensitivity. (4) Select and assemble individualised video clips for review in the group. (5) Use the manual to assist in facilitating multiple individualised video reviews with each client over the course of a 20-week minimum intervention. In comparison, COS-p contains two main elements: (1) Facilitate video reviews using the COS-p manual, with eight weekly sessions. (2) Use the COS-p fidelity journal to reflect on the experiences from the sessions (Hoffman et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2014). According to the COS website (https://www.circleofsecurityinternational.com), another main difference is that while only licensed clinicians can be trained in the COS Intervention model – which includes ten days of training, an exam and at least one year of supervised practice – the COS-p programme can be conducted by anyone who completes a four-day training programme.

The parent training method, COS-p, is a universal structured programme that intends to help caregivers increase their capacity to serve as sources of security for their children, with the idea that this strengthens caregiver sensitivity and reduces the risk of insecure and disorganised attachment. The programme offers caregivers a theoretically based understanding of the complexity of the attachment system and how it contributes to infants’ and toddlers’ development of their sense of security and competence. Childhood experiences of parental insensitivity, as well as insecure and disorganised attachment, are precursors of a variety of problematic developmental outcomes. For some outcomes – such as externalising problems, physiological dysregulation and other forms of developmental psychopathology – disorganised attachment brings a heightened risk, even in comparison to other types of insecure attachments (Fearon et al., 2010; Thompson, 2016). COS-p is an attachment-based intervention, stemming primarily from the work of psychologists John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth (Ainsworth et al., 1978), and functions as a method of promoting safe attachment between caregivers and children to prevent child mental health problems (Hoffman et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2014). However, in contrast to the other COS programmes, COS-p does not measure the quality of attachment, as the programme focuses on increasing childcare providers’ awareness of attachment. The aims of COS-p include developing parents’ observation and inferential skills related to understanding their child’s needs, increasing sensitivity towards their child, aiding in emotional regulation, as well decreasing any of their negative attributions to their child (Powell et al., 2014). The model is based on the belief that caregivers who are emotionally present with their children and helpful in processing strong feelings act to contain distress and help the children develop the ability to accomplish this themselves and become self-regulating.

COS-p is described as a preventive psycho-educational parental guidance programme, primarily developed for the school health service, health centres and kindergarten. It targets the parents of the youngest children, as it is theorised that the intervention will be more effective, the earlier it is implemented (Hoffmann et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2014). COS-p is offered to parents who can choose to participate, either individually or in groups, in an intervention for enhancing attachment in early parent-child relationships. The parental training method is a pre-prepared manual programme that normally involves 6–8 guidance sequences. There is no formal requirement to adhere to the official manual; however, in a survey of 423 Norwegian supervisors, 92% reported following the manual and using the programme as taught in their work (Brandtzæg & Thorsteinson, 2014).

Despite the generally scarce scientific information available regarding the effectiveness of parenting education programmes developed specifically for families in the child welfare system, COS-p has been listed as not possible to be scientifically evaluated due to the limited research and considerable variability in its delivery (Caruana, 2016). Thus, based on the COS Intervention research studies, there is an overall expectation of COS-p’s effectiveness when the participants are at-risk parents; it is expected to improve caregiver skills, confidence, self-efficacy and wellbeing, as both models are based on the same theoretical framework (Caruana, 2016; Powell et al., 2014). However, questions have been raised about whether the expected effectiveness applies generally and if it is transferable to multi-problem families in the CPS context.

Characteristics of families in multi-problem situations

In recent decades, there has been extensive research on the risk factors’ effects on the development of psychopathology among children and adolescents (Kolthof et al., 2014). The problems that such families experience include parenting issues, financial debt, psychiatric problems, troubled relationships, health and housing-related issues, intellectual disabilities, social class contrasts (e.g., poor, uneducated parents, lack of social support, many stressful life events) and repeated contacts with social authorities or the criminal justice system (Bodden & Decović, 2010; Holwerda et al., 2014; Sameroff, 2000). Moreover, there is considerable overlap among the risk factors contributing to different disorders, such as depression, behavioural problems, substance abuse or schizophrenia (Sameroff, 2000). A disorganised home (an environment with high noise levels, over-crowding and little regularity or routines) can also lead to unhealthy socio-emotional development. This may result in children’s instability in school and in the home situation, which increases the risk of negative effects on their cognitive development (Coldwell et al., 2006; Evans, 2004).

The problems in these families are described as multiple, varying and complex (Kolthof et al., 2014; Tausendfreund et al., 2016). The aspect of multiplicity means that the families have to cope with several problems simultaneously. These problems exist in different areas of life, causing them to vary as life changes over time. Furthermore, the problems are interwoven, modifying one another in many ways and leading to increasingly complex situations. The interaction between socioeconomic and psychosocial problems appears to be responsible for the difficulties that some families experience in their attempts to handle everyday life successfully (Bodden & Decović, 2010). The complexity of these families’ situations indicates that other stress-creating factors in life may need to be reduced before they enter reflection processes regarding how to behave towards their children, such as those offered in the COS-p programme. At the same time, it is reasonable to question whether the parents actually need such a programme or if their parenting skills would adjust accordingly if they would receive comprehensive help based on the multi-problem complexity of their situations.

In addition to the problems in the families, their ability to solve their issues should also be taken into account as reciprocal conditions in change processes. Thus, it is not the abundance of problems that distinguishes families in multi-problem situations; rather, it is their limited ability to solve their problems in a persistent way (Spratt, 2011), which leads to encounters with the social authorities and the social welfare system.

Methods

Search strategy

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Moher et al., 2009). The review followed the methodology outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., 2019). The database searches were originally conducted in June 2018 and updated in March 2020, encompassing 13 international bibliographical databases: Oria, Cinahl, Academic, PubMed, Campell, ProQuest, EBSCOhost, Wiley, Social Care Online, Sage, SpringerLinks, Taylor & Francis, and SweMed. The search for grey literature entailed contacting both national and international coordinators of the programme and searching for ongoing, relevant projects, as well as examining the official website of COS International (https://www.circleofsecurityinternational.com/).

The following search terms were modified, where appropriate, to meet the search requirements of each database: “Circle of Security Parenting or Circle of Security - Parenting or COS-p” AND “Interven* or program* or child services* or social services* or CPS* or child welfare*” AND “outcome* or evaluat* or effect* or experiment* or trial* or compare* or impact* or consequen* or research” AND “Multi-Problem* or multiproblem* or risk* or at-risk* or high-risk*. The search included peer-reviewed studies, non-peer-reviewed studies and grey literature (e.g., theses, research reports, conference papers) that identified the topic.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

A population, intervention, comparators, outcome and study design (PICOS) framework was used to support the study selection process. The studies to be included in this review had to match predetermined criteria according to the PICOS approach (Table 1).

Table 1: PICOS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies

|

Parameter |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

Population / problem |

Research studies on the effectiveness of COS-p intervention, where participants report a minimum of 2 specifically defined risk factors. |

Studies that examine the use of COS-p in general, without identifying risk factors among the attendees Studies targeting families with one, or none identified risk factors Studies that examine the effectiveness of COS-p, where the attendees are others than parents (e.g. child care providers, foster parents) |

|

Intervention |

Circle of Security Parenting (COS-p), both group and individual model Program adhered closely to the manual, 6-10 week program period |

All other COS interventions, e.g. COS, COSi, and COS-hv4 Program where the manual is partial or random followed. Program period less than 6 weeks or longer than 10 weeks. |

|

Comparators |

What effectiveness does the COS-p program have for participants living in a multi-problem situation |

|

|

Outcome |

Primary outcome measures: Change in parenting skills and strengthening of the parent-child relationship. Secondary outcome measures: Benefits for the child, e.g. measured in changes in the child’s behavior |

|

|

Study design |

Randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, not controlled trials, and retrospective, prospective, or concurrent cohort studies. Single case studies. Peer-reviewed |

Reviews, expert opinion, comments, letter to editor, conference reports. Outcome measured solely on participants’ experience, without additional measures. Studies with no outcomes reported. Non-peer-reviewed Implementation studies |

Initially, two reviewers screened the publications based on the title and the abstract to identify any clear irrelevance (e.g., family childcare providers, implementation studies) to the current review or any duplication. The publications that passed the first screening were screened again by the same two reviewers based on the full-text version, and disagreements were handled according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s “reliability and reaching consensus” tool (Higgins et al., 2019). The studies that examined the use of COS-p in general, without identifying multiple risk factors among the attendees, were excluded. To be included, the studies should have examined the effectiveness of the COS-p programme when aimed at participants with at least two specifically defined risk factors affecting their lives. The studies targeting families with one or no identified risk factor were not included, as multi-problem families have more compound problems and are therefore expected to have specific needs. When the COS-p programme is aimed at multi-problem families, it is expected to be more targeted than when it addresses a broader category of at-risk parents that seeks to prevent their children’s maladjustment.

Only those studies where the COS-p programme adhered closely to the manual were included, and these had a programme duration that varied between 6 and 10 weeks. Both individual and group interventions were included. As this is a systematic review of the intervention’s effectiveness, only the studies that measured effectiveness were included. Self-reports of the participants’ experiences of COS-p, without observations or quantitative measures to examine the programme outcomes for the participants, were excluded. Furthermore, a non-statistical narrative approach was used to analyse the studies due to the heterogeneity of the outcome measures.

Quality assessment strategy and risk of bias

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s “risk of bias” tool, as adapted from Higgins et al. (2019). This tool assesses five potential sources of bias: selection, performance, attrition, reporting and other biases. Bias is assessed as a judgement (high, low or unclear) for individual elements from the five sources as a way to evaluate validity and the risk of over- or under-estimating the true effectiveness of COS-p when used for multi-problem families. A random selection (three papers) was quality checked by a second independent reviewer to ensure reliable ratings.

Data extraction

The data were extracted from the included studies using a predetermined form, and any missing or unclear information was marked next to the relevant item. The extracted information included (1) study design, (2) sample characteristics, (3) setting, (4) intervention details, (5) outcome measures and (6) child age at baseline. Secondary outcomes concerned other child development markers, such as cognitive development, psychomotor development, parent sensitivity and attachment classification.

The extraction was performed by the author and thereafter controlled by three peers. Disagreements were handled according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s “reliability and reaching consensus” tool (Higgins et al., 2019).

Results

Study selection

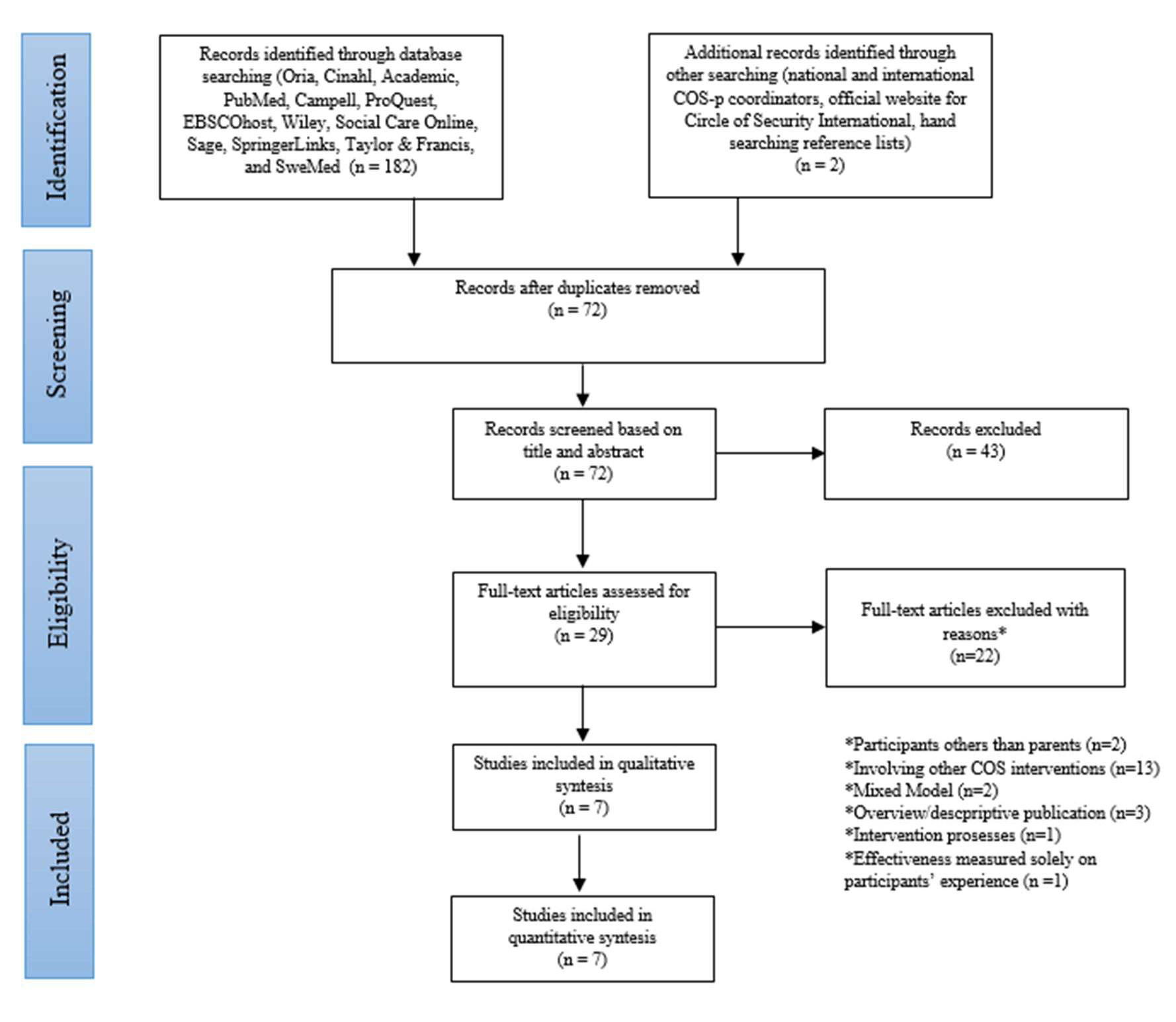

The initial systematic search in reference databases generated a total of 182 potentially relevant hits. Two additional studies were identified from other sources, including manually searching reference lists. Out of 72 unduplicated titles and abstracts, 29 articles were assessed (full text) for eligibility. Seven original publications, published between 2014 and 2018, met the eligibility criteria and were selected for the systematic review (Table 2).

Table 2: PRISMA diagram describing the search and selection process

Study characteristics

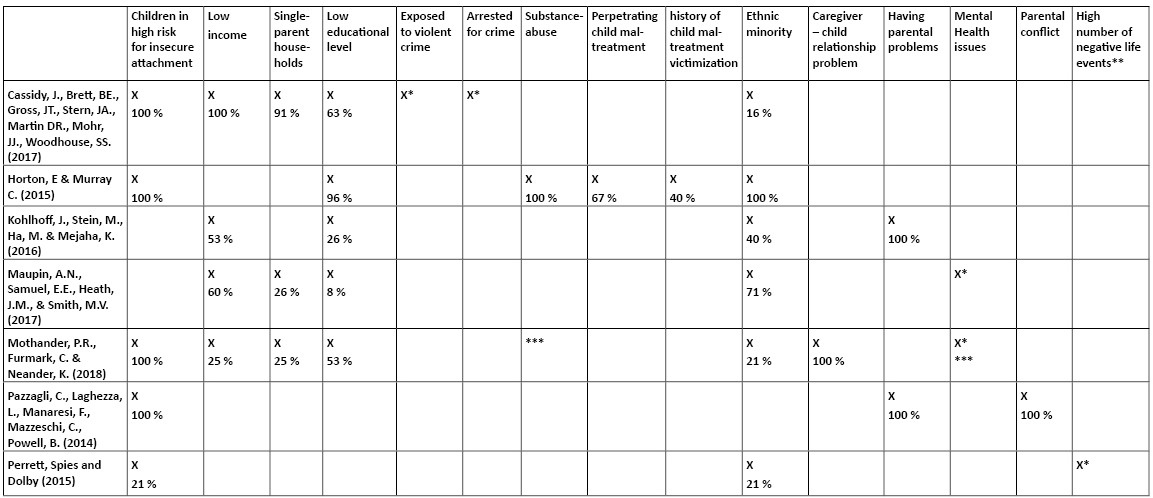

The included studies examined interventions aimed at families experiencing difficulties with special needs in more than two areas. The areas of difficulty were as follows: low income, single-parent household, low educational level, exposure to violent crime, arrest for a crime, substance abuse, history of perpetrating child maltreatment, history of child maltreatment victimisation and ethnic minority status. Some samples were further characterised by insecure attachment, risk of developmental delay or parental problems, among others. Table 3 presents an overview of the occurrence and frequency of various participant characteristics.

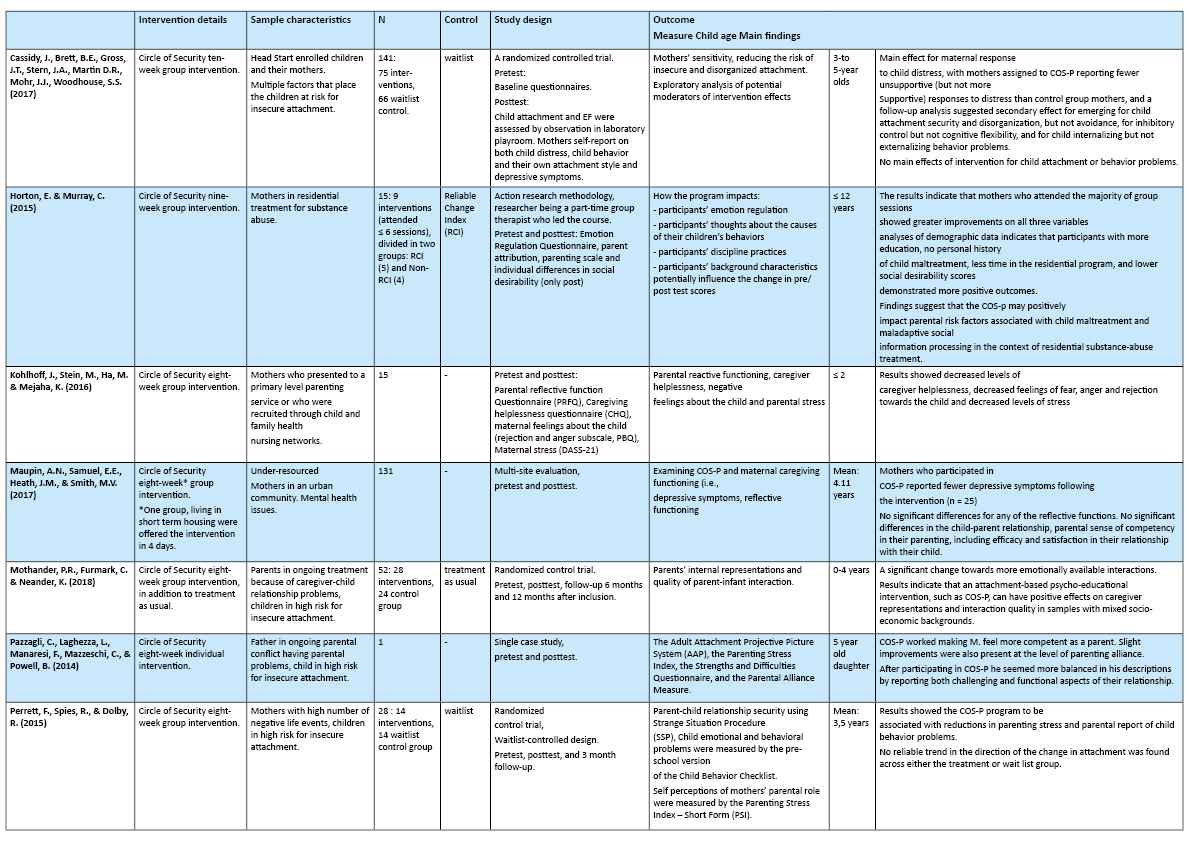

The parents’ ages ranged from 22 to 44 years, with the participants in five studies reported as mothers (Cassidy et al., 2017; Horton & Murray, 2015; Kohlhoff et al., 2016; Maupin et al., 2017; Perrett et al., 2015). One study reported the participants as fathers (Pazzagli et al., 2014), while another included both mothers and fathers (Mothander et al., 2018). Horton and Murray (2015) offered participation to both mothers and fathers; however, only mothers signed up. Three studies also included families with more than one child (Horton & Murray, 2015; Kohlhoff et al., 2016; Maupin et al., 2017) but encouraged the participants to focus on their youngest child’s behaviour and their experiences with him or her.

Table 3: Participant characteristics

* Not stated per participant

** Not specified type of negative life events

*** Caregivers with current drug and/or alcohol abuse, acute mental health problems such as significant depression, or caregivers acting out narcissistic issues by denigrating others were excluded from the study

Description of studies

Included studies

The literature search identified eight articles focusing on the use of COS-p as an intervention for multi-problem families where at least two risk factors were identified. One study (Kimmel et al., 2017) was excluded because it only explored the participants’ experiences. Table 4 provides an overview of the seven included studies. None of the studies identified COS-p intervention use for families within the child welfare system; however, two studies (Horton & Murray, 2015; Maupin et al., 2017) identified participants with active CPS cases. In any country, no current evidence supports targeted applications of COS-p for multi-problem families or using the programme for families that need help from child services. However, this systematic review has identified seven studies that contribute to the work on identifying the effectiveness of COS-p among families living with multi-risk factors. All empirical studies were peer reviewed.

Additionally, the literature search identified no studies focusing on the use of COS-p in culturally or developmentally diverse populations, leading to the assumption that no empirical evaluation of COS-p in such populations has been conducted so far.

Intervention

In six of the included studies (Cassidy et al., 2017; Horton & Murray, 2015; Kohlhoff et al., 2016; Maupin et al., 2017; Mothander et al., 2018; Perrett et al., 2015), the intervention was conducted in the form of weekly group meetings under the condition that the participating caregivers had not been earlier involved in a COS intervention. Pazzagli et al. (2014) conducted a single case study, where the intervention was administered in the form of individual sessions.

Table 4: Description of included studies

Risk of bias

Evaluation studies on parenting programmes usually include small to medium sample sizes and are thus difficult to interpret, as they are not blinded and often rely on self-reported outcome measures. As all studies included here were conducted in clinics, bias might have been introduced in several places during the COS-p programme. As the researchers or the data collectors were also the group facilitators, subtle bias could have influenced the facilitators’ responses to the participants during the intervention and biased the participants’ responses during the data collection. However, in all the included studies, the authors considered the risk of bias to be low.

Outcomes

All studies included an analysis of the effects of one or both of the outcomes that COS-p directly targets: child attachment (security, avoidance and organised versus disorganised classification) and caregivers’ responses to child distress (supportive and unsupportive responses). Three of the studies (Cassidy et al., 2017; Pazzagli et al., 2014; Perrett et al., 2015) also analysed the effects of the intervention on possible secondary outcomes, such as child behaviour problems (internalising and externalising), child executive functioning (inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility) or both.

Effect of the intervention on child attachment

Cassidy et al. (2017) found no significant effects of intervention on continuous attachment outcomes (e.g., security or avoidance). Moreover, the rates of disorganised attachment did not differ between the treatment and the control groups. Moderation of the intervention effect was explored by conducting an exploratory analysis to examine whether dimensions of adult attachment style (e.g., anxiety and avoidance) or maternal depressive symptoms moderated the intervention effect. An insignificant moderated effect was identified; maternal attachment avoidance moderated intervention effects on both child security and rates of disorganisation. When the mothers’ scores were one standard deviation (SD) above the mean on attachment avoidance, the children in the intervention group tended to be both more secure and less disorganised than the children in the control group. However, there was no main treatment effect on the security or the disorganisation of the mothers who had a mean score on attachment avoidance

The children of the mothers who scored one SD below the mean on attachment avoidance displayed less security than the children in the control group. There was no evidence of a main treatment effect on disorganisation in this group (Cassidy et al., 2017). Maternal attachment avoidance did not moderate the effects on child avoidance.

No other variables moderated the intervention effects on child attachment. These included (1) maternal attachment anxiety on child security, child avoidance or disorganisation and (2) maternal depression symptoms on child security, child avoidance or disorganisation. Neither of these was found by Cassidy et al. (2017) and Perrett et al. (2015). Furthermore, Maupin et al. (2017) did not find any effectiveness on the child–parent relationship.

Effect of the intervention on caregivers’ responses to child distress

Cassidy et al. (2017) found that the use of the COS-p intervention reduced the mothers’ unsupportive responses to child distress. However, the intervention did not alter the mothers’ supportive responses to child distress. The findings were not moderated by maternal attachment anxiety, maternal attachment avoidance or maternal depression symptoms.

Measuring individual differences in two commonly utilised emotion-regulation strategies, that is, reappraisal and suppression using the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003), Horton and Murray (2015) identified a small mean trend towards increasing reappraisal strategies and decreasing suppression among the study participants who attended the COS-p intervention sessions. These scores indicate a better implementation of beneficial emotion-regulation strategies. For the reappraisal strategies, five participants showed improvement, one stayed the same, and three had post-test scores that were lower than their pre-test scores. On suppression strategies, four participants showed improvement, one stayed the same, and four showed a negative development in this area. Horton and Murray (2015) identified four background variables that were qualitatively associated with reliable change on the measures concerning the effectiveness of COS-p. Generally, participants with more education, no personal history of child maltreatment victimisation, less time in the residential substance-abuse treatment programme and lower social desirability scores showed reliable change. In contrast, participants who had less education, a personal history of child maltreatment and more time in the residential programme were associated with a reduced effectiveness of the intervention. A history of perpetrating child maltreatment, the number of sessions attended and the number of children in the family had no impact on the intervention’s effectiveness. However, Maupin et al. (2017) found the intervention ineffective in parental competency, including efficacy and satisfaction with their relationship with their child.

Pazzagli et al. (2014) reported a single case study of a father who took part in the COS-p intervention in the context of conflict for the custody of his five-year-old daughter. He showed improvements in agency of self, capacity to use internal resources, parental stress and perception of his child’s functioning. Reduction in parental stress was also reported by Perrett et al. (2015), who used a waitlist-controlled design to evaluate the efficacy of COS-p in a small sample of mothers with young children (mean age: 3.5 years). Furthermore, Kohlhoff et al. (2016) found the intervention to be associated with a decreased level of caregiver helplessness and maternal stress, as well as a decreased feeling of fear, anger and rejection towards the child.

Mothers who participated in an intervention (Maupin et al., 2017) reported significantly fewer depression symptoms compared with their symptoms before attending the COS-p programme, while Mothander et al. (2018) reported positive changes in parents’ representations and responsiveness to their child after attending the intervention programme. The findings indicate that it is possible to enhance high-risk parents’ representations about themselves as parents and their caregiving through intervention. However, Maupin et al. (2017) did not find any effectiveness for any of the reflective functioning scales, including prementalising, certainty about mental states, and interest and curiosity.

Effect of the intervention on child behaviour problems

Three studies (Cassidy et al., 2017; Pazzagli et al., 2014; Perrett et al., 2015) analysed the effects of the COS-p intervention on child behaviour problems. All studies found the intervention to have no significant effect on child internalising or externalising behaviour problems.

Cassidy et al. (2017) reported moderated effects, which showed that the children in the intervention group had fewer mother-reported internalising problems than the children in the control group when the mothers’ scores were one SD below the mean on attachment anxiety or on depression symptoms. There were no specific effects that predicted child internalising problems when the mothers had mean scores on attachment anxiety or depression symptoms, nor were intervention effects on internalising problems moderated by maternal attachment avoidance. For externalising problems, the intervention effect was not moderated by maternal attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance or depression symptoms (Cassidy et al., 2017).

Both Pazzagli et al. (2014) and Perrett et al. (2015) measured the parental perception of their child’s emotional and behavioural problems. Perrett et al. (2015) found that the majority of the participants reported that their children’s behaviour was within the normal range. However, four participants reported that their children’s behaviour was outside the normal range, with three participants reporting reduced problems after attending the COS-p programme. The improvement was maintained at a three-month follow-up. Pazzagli et al. (2014) reported similar findings, where the participants progressed from reporting their children’s severe difficulties with attention, concentration and hyperactivity to reporting their children’s good behavioural and emotional functions after the participants attended the COS-p programme.

Effect of the intervention on child executive functioning

Only one of the studies (Cassidy et al., 2017) analysed the effect of the COS-p intervention on child executive functioning and found no significant effect. After the study controlled for maternal age and marital status, the children of the mothers in the intervention group showed better inhibitory control than the children of the mothers in the control group.

Discussion

This systematic review on the effectiveness of COS-p as a training programme for caregivers from multi-problem families provides an overview of the programme’s potential effectiveness, both for the caregivers and with respect to benefits for the children. The findings’ strengths include some improvements in reducing parental stress, increasing self-efficacy and parenting skills, and promoting their understanding of child behaviour. However, there is no conclusive evidence that COS-p assists in increasing the security of the parent-child attachment relationship. As this systematic review shows, COS-p sessions in group settings have demonstrated some effectiveness and suitability for multi-problem caregivers who want to develop parenting skills, but little evidence supports the intervention’s effects on child behaviour or emotional regulation. While child behaviour changes have been measured in three included studies (Cassidy et al., 2017; Pazzagli et al., 2014; Perrett et al., 2015), the child’s individual characteristics are generally not incorporated into COS-p evaluations because they are not directly taken into account in the programme. Accordingly, the possibility that the reported change is due to general characteristics of a parenting group rather than to the specific content of COS-p cannot be ruled out. Additionally, all but two studies (Mothander et al., 2018; Perrett et al., 2015) report an outcome that occurred immediately after the intervention ended, precluding the detection of possible “sleeper effects” found in intervention studies with long-term follow-up assessments (Seitz, 1981). Trials without a follow-up have no recourse for testing, regardless of whether the reported effect is the beginning of developmental changes in the lives of families affected by COS-p or the reported effect is short term and will wane over time as parents fall back into pre-intervention habits.

Cultural challenges for the COS-p programme

This review highlights that in six out of the seven studies, there were participants from ethnic minority groups (Table 3). However, none of the included studies identified the ethnic groups to which these participants belonged, mentioned any language barriers or reflected on whether there was a need for an adjustment of the COS-p programme due to cultural challenges.

COS-p is an overall prevention approach. With its theoretical basis on attachment and its focus on educating caregivers about the ways to enhance this attachment, COS-p aims to build on the parents’ pre-intervention understandings of their caring role, regardless of their skill level or the risk factors present, as it improves their knowledge of child development and behaviour (Cooper et al., 2009). However, a variety of delivery methods may be required to achieve what is defined as necessary changes in multi-problem families. For instance, behavioural interventions and individualised training are considered more suitable for parents with intellectual disabilities, especially where they utilise home visits and skill-based strategies, such as modelling, visual aids and so on (Feldman, 2010). For indigenous families, longer-term home-based programmes that focus on the needs and the strengths of parent and child have been more successful; if a mainstream programme would be adapted for this population, community involvement and consultation would be required to ensure its relevance and cultural support (Mildon & Polimeni, 2012). This systematic review did not find any current evidence of targeted applications of COS-p for culturally or developmentally diverse populations, which is a current limitation on its applicability for these groups. Secure attachment is largely accepted as a quality of harmonious and healthy parent-child relationships, but its expression and forms are culturally specific and may be affected by external factors, such as poverty or parental stress, and these considerations need to be incorporated into any programme offered to multi-problem families.

What works for whom

COS-p was designed to increase caregivers’ sensitivity to child distress and reduce the risk of insecure and disorganised attachment. The examination of potential moderators of intervention efficacy allows insights into the important issue of “what works for whom”. As noted by Rothwell (2005), it is important to consider interaction effects due to the potential for any intervention to affect subgroups of individuals differently. Potential disordinal treatment-subgroup interactions would be particularly essential to consider due to their clinical implications for individual outcomes (Byar, 1985). For example, secure attachment has been shown to predict aspects of executive functioning, including working memory, cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control, of preschool children (Bernier et al., 2012). Although secure attachment is linked to key dimensions of caregiving for children with regard to their executive functioning (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bernier & Dozier, 2003; Whipple et al., 2011), no study has shown COS-p’s reducing effects on this matter in the context of multi-problem families. Based on this review, no conclusive evidence shows that the COS-p programme assists in increasing the security of parent-child attachment relationships when the participants live in multi-problem situations, although small sample sizes, measurement errors and sample characteristics are possible alternative explanations for this lack of positive change. With problems as complex as those described for families in multi-problem situations, it is reasonable to question whether a parent training method such as COS-p will contribute to necessary changes in multi-problem families and if so, in what context. This is particularly salient when considering the cognitive flexibility required for participation in the COS-p programme and the possible need to reduce other stress-creating factors in the families before the parents become emotionally and cognitively available for the reflection level that the COS-p programme requires.

Limitations

Although this study aimed to establish a systematic overview of the COS-p intervention’s potential effectiveness concerning both caregivers and benefits for children living with multi-problem families, some main limitations need to be addressed.

First, none of the included studies targeted families in multi-problem situations. Although the participants were dealing with two risk factors or more at the time of participation, nothing was mentioned about how the risk factors affected their daily life. With its theoretical basis on attachment and its focus on educating parents about the ways to enhance this attachment, COS-p is able to provide such an approach. It aims to build on the parents’ pre-intervention understandings of their caring role, regardless of their skill level or the risk factors present, by enhancing their knowledge of child development and behaviour (Cooper et al., 2009). However, none of the studies questioned whether the families’ life situations would affect the outcomes. It is therefore not recommended that potential effectiveness be transferred to a general expectation of what families in multi-problem situations would gain from attending the COS-p programme.

Second, this review showed that the researchers or the data collectors in each study were also the group facilitators; thus, subtle bias could have influenced the facilitators’ responses to the participants during the intervention and biased the participants’ responses during the data collection. As the data collection and evaluation were often not blinded and based on self-reported outcome measures, this would represent a major limitation to the ability to generalise the expected effectiveness of the COS-p programme.

Third, the participants reported a wide variety of risk factors, without the participant demographics being included in the study designs. The studies only measured the effects of participation in the COS-p programme in general. It was not possible to identify whether some risk factors would affect the programme’s effectiveness more than others. Consequently, it was also not possible to provide a clear recommendation on which families, if any, would gain from participating in the COS-p programme while living in multi-problem situations.

Fourth, this review lacked information on the long-term effectiveness of participating in the COS-p programme. Only two of the included studies had a follow-up design, with measures at 3 months (Perrett et al., 2015) or 4 and 10 months (Mothander et al., 2018) after participation in the COS-p programme.

Fifth, three of the studies did not include a control group in the study design (Kohlhoff et al., 2016; Maupin et al., 2017; Pazzagli et al., 2014). This made it difficult to determine whether the effectiveness of participation in the COS-p programme, or lack thereof, could be expected when delivered to multi-problem families, as this could be the result of other external causes. Further research is therefore needed to determine what effect, if any, participation in the COS-p programme may have for parents living in multi-problem situations.

Conclusion

This systematic review on the effectiveness of COS-p as a parent training programme for caregivers from multi-problem families shows that despite some promising results of these trials, remarkably little has been published about this topic. There have been studies on separate and isolated factors affecting caregivers but none on the effect of the accumulation of risk factors and how this may or may not influence the potential effectiveness of COS-p. A common denominator across the studies included in this review is an indication of a positive outcome in terms of parental stress reduction. Given the limited number of studies, further research is needed before defining what positive effects multi-problem families can expect from participating in the COS-p programme.

Litteraturhenvisninger

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bernier, A., Carlson, S. M., Deschênes, M., & Matte-Gagné, C. (2012). Social factors in the development of early executive functioning. A closer look at the caregiving environment. Developmental Science, 15(1), 12-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01093.x

Bernier, A., & Dozier, M. (2003). Bridging the attachment transmission gap: The role of maternal mind-mindedness. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(4), 355-365. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250244000399

Bodden, D., & Deković, M. (2010). Multiprobleemgezinnen ontrafeld [Multi-problem families unravelled]. Tijdschrift Voor Orthopedagogiek, 49(6), 259-271.

Brandtzæg, I., & Thorsteinson, S. (2014, June 14-18). Implementation of Circle of Security in Scandinavia [Conference presentation]. World Association of Infant Mental Health, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Bråten, B., & Sønsterudbråten, S. (2016). Foreldreveiledning - virker det? En kunnskapsstatus (Fafo-rapport 2016:29). Fafo Institutt for arbeidsliv- og velferdsforskning.

Byar, D. P. (1985). Assessing apparent treatment-covariate interactions in randomized clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine, 4(3), 255-263. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780040304

Caruana, T. (2016). Theory and research considerations in implementing the Circle of Security Parenting (COS-P) Program. Communities, Children and Families Australia, 10(1), 45-58.

Cassidy, J., Brett, B. E., Gross, J. T., Stern, J. A., Martin, D. R., Mohr, J. J., & Woodhouse, S. S. (2017). Circle of Security-Parenting: A randomized controlled trial in Head Start. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 651-673. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000244

Christiansen, Ø., Bakketeig, E., Skilbred, D., Madsen, C., Havnen, K. J. S., Aarland, K., & Backe-Hansen, E. (2015). Forskningskunnskap om barnevernets hjelpetiltak. Bergen: Uni Research Helse, Regionalt kunnskapssenter for barn og unge (RKBU Vest).

Coldwell, J., Pike, A., & Dunn, J. (2006). Household chaos - links with parenting and child behaviour. Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 1116-1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01655.x

Cooper, G., Hoffman, K., & Powell, B. (2009). Circle of Security Parenting: A relationship based parenting program. Facilitator DVD Manual 5.0. Spokane, WA: Circle of Security International.

EIF Guidebook (2019). Circle of Security Parenting. Early Intervention Foundation. https://guidebook.eif.org.uk/programme/circle-of-security-parenting#key-programme-characteristics.

Evans, G. W. (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59, 77-92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77

Fearon, R.P., Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M.J., Van IJzendoorn, M.H., Lapsley, A-M., & Roisman, G.I. (2010). The Significance of Insecure Attachment and Disorganization in the Development of Children's Externalizing Behavior: A Meta‐Analytic Study. Child Development, 81(2), 435-456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x

Feldman, M. (2010). Parenting education programs. In Llewellyn, G., Traustadottir, R., McDonnell, D. & Sigurjonsdottir, S.B. (ed.). Parents with intellectual disabilities; Past, present and futures, 121-137. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470660393.ch8

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348-362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604

Hoffman K. T., Marvin, R. S., Cooper, G., & Powell, B. (2006). Changing toddlers' and preschoolers' attachment classifications: The Circle of Security intervention. Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1017-1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1017

Holwerda, A., Reijneveld, S. A., & Jansen, D. E. M. C. (2014). De effectiviteit van hulpverlening aan multiprobleemgezinnen: Een overzicht [The effectiveness of care for multiproblem families: An overview]. University Medical Center Groningen.

Horton, E., & Murray, C. (2015). A quantitative exploratory evaluation of the Circle of Security-Parenting program with mothers in residential substance-abuse treatment. Infant Mental Health, 36, 320-336. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21514

Kimmel, M. C., Cluxton-Keller, F., Frosch, E., Carter, T., & Solomon, B. S. (2017). Maternal experiences in a parenting group delivered in an urban general pediatric clinic. Clinical Pediatrics, 56(1), 13-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922816675012

Kohlhoff, J., Stein, M., Ha, M., & Mejaha, K. (2016). The circle of security parenting (cos-p) intervention: Pilot evaluation. Australian Journal of Child and Family Health Nursing, 13(1), 3-7.

Kolthof, H. J., Kikkert, M. J., & Dekker, J. (2014). Multiproblem or multirisk families? A broad review of the literature. Child and Adolescent Behavior, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.4172/2375-4494.1000148

Maupin, A. N., Samuel, E. E., Nappi, S. M., Heath, J. M., & Smith, M. V. (2017). Disseminating a parenting intervention in the community: Experiences from a multi-site evaluation. Child and Family Studies, 26, 3079-3092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0804-7

Mildon, R., & Polimeni, M. (2012). Parenting in the early years: Effectiveness of parenting support programs for Indigenous families. Closing the Gap, resource sheet no. 16. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Mothander, P. R., Furmark, C., & Neander, K. (2018). Adding "Circle of Security - Parenting" to treatment as usual in three Swedish infant mental health clinics. Effects on parents' internal representations and quality of parent-infant interaction. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59(3), 262-272. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12419

Pazzagli, C., Laghezza, L., Manaresi, F., Mazzeschi, C., & Powell, B. (2014). The circle of security parenting and parental conflict: A single case study. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00887

Perrett, F., Spies, R., & Dolby, R. (2015, August 13-14). Enhancing familial mental health through parental reflection and education: Circle of Security-parenting program. [Conference presentation]. 16th International Mental Health Conference, Gold Coast, Australia.

Plauborg, R., & Jacobsen, A. L. (2017). Cos-P: Circle of Security - Parenting. Socialstyrelsen. https://vidensportal.dk/temaer/Omsorgssvigt/indsatser/circle-of-security-2013-parenting-cos-p

Powell, B., Cooper, G., Hoffman, K., & Marvin, R. (2014). The Circle of Security intervention: Enhancing attachment in early parent-child relationship. Guilford.

Rothwell, W. J. (2005). Editorial and introduction. International Journal of Training and Development, 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.1111./j.1360-3736.2005.00217.x

Sameroff, A. J. (2000). Developmental systems and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 297-312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400003035

Seitz, V. (1981). Intervention and sleeper effects: A reply to Clark and Clark. Developmental Review, 1(4), 361-373. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(81)90031-9

Spratt, T. (2011). Families with multiple problems: Some challenges in identifying and providing services to those experiencing adversities across the life course. Journal of Social Work, 11(4), 343-357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017310379256

Tausendfreund, T., Knot-Dickscheit, J., Schulze, G.C., & Grietens, H. (2016). Families in Multi-Problem Situations: Backgrounds, Characteristics and Care Services. Child and Youth Services, 37(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2015.1052133

Thompson, R. A. (2016). Early attachment and later development: Reframing the questions. In Cassidy, J. & Shaver, P.R. (ed.). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications, 330-348. 3rd Ed. Guilford Press.

Whipple, N., Bernier, A., & Mageau, G. A. (2011). A dimensional approach to maternal attachment state of mind: Relations to maternal sensitivity and maternal autonomy support. Developmental Psychology, 47(2), 396-403. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021310